|

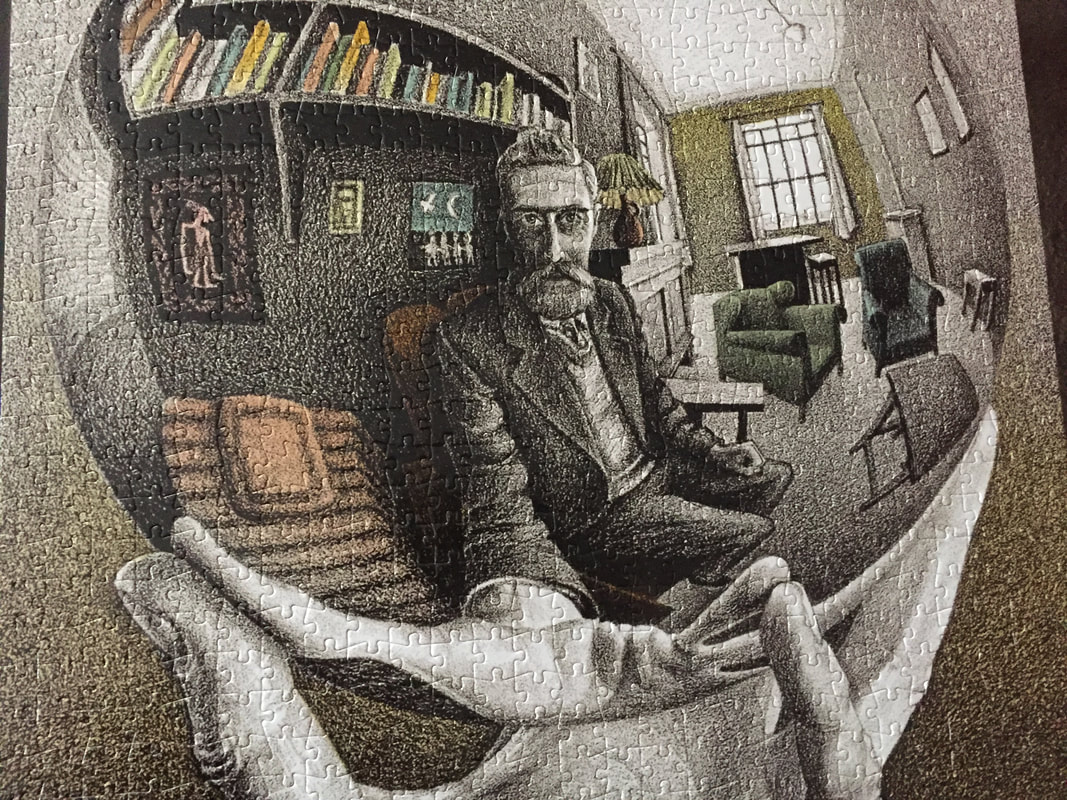

Max Escher gazes up from the self-portrait that absorbed much of my January. Nearly devoid of crisp lines or vivid colors, right angles skewed by his reflecting sphere, it launched me more than once into searching the floor for a piece I knew must be missing.

Winter is jigsaw puzzle season. We’re fortunate to have a suitable table available, since the holidays, for as long as the thousand pieces take to assemble. Though I feared this one might take months, gradually my perceptions sharpened. Distinctions of tone and texture emerged that were invisible at first. This temporary shift in perception is as predictable as the conviction that a piece is missing. For a time, the world around me grows more vivid, too. Colorless midwinter takes on myriad shades of brown, gray, and white. Like skills or muscles, the senses we exercise grow stronger. Perhaps that’s why writers are encouraged to carry notepads, not just to capture phrases or incidents for future reference, but to hone the skill of noticing.

2 Comments

One delight of reading historical fiction is the discovery of cultures I didn’t know existed. Reading Mycroft Holmes by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Anna Waterhouse, I wondered if the “Merikins” Sherlock’s brother encounters in Trinidad were a figment of the authors’ imagination. They turn out to be quite real.

During the War of 1812, hundreds of American slaves escaped to the British navy for a promise of freedom and sixteen acres of land. Afterward these “Merikins” and their families settled six hilltop “company villages” in southern Trinidad, corresponding to the six companies of their service in the Colonial Marines. The Merikins left a lasting mark on Trinidadian culture. They’re credited with introducing hill rice as a major crop. Merikin descendants celebrate a heritage that includes their Baptist faith and the gayap tradition of “each one, help one.” Historical markers identify the company village sites, two of which—Fifth Company and Sixth Company—retain their original place names. Photo from the National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago. Researching a college term paper on early Czech nationalism, I learned medieval theologians didn’t use Latin only to please the Church.* Everyday languages like Czech lacked a vocabulary for complex theological ideas; ordinary folk didn’t need it. Language, in turn, shaped and limited what non-scholars could think. It’s hard to discuss or even contemplate matters for which you lack the words.

New terms (neologisms) and new ideas grew hand in hand. Over time, languages became richer and more complex. Specialized vocabulary (jargon) within a skill or interest group made communication more precise. Plumbers confer about a leak in terms that mean nothing to me, with far better results than if they depended on my floundering “that round part on the bottom.” Neologisms like blog and webinar gain easy acceptance. Not so with death tax, feminazi, intersectionality, and microaggression. Such terms flag the user’s sympathies.** Some serve no other purpose (buzzwords). Consider Democrat Party vs. Democratic Party, or people of color vs. colored people. The choice of phrasing communicates nothing but the leanings of the speaker. * Of course, Latin also let scholars communicate internationally, as French did later and English does today. ** Some of these terms also facilitate precise discussion. It wasn’t so much a New Year’s resolution as a turn-of-the-year experiment. Anticipating six days in a row with no scheduled obligations, I resolved to spend the week writing at a pace I hadn’t sustained in a while and see what happened. Would focus and flow come back?

Recently I happened on an article about the brain states of zebrafish. They have a limbic system (involved in emotion) similar to humans and they’re easier to study. Researchers have found a hub of neurons that control a brain-wide motivational switch. When it’s activated, a zebrafish goes into high focus for a limited time to chase prey. Unrelated skills are suppressed until the hunting state winds down. Then the zebrafish swims about restlessly exploring its environment. Focus or explore? I identify with the zebrafish in its need for both. My New Year’s experiment managed to reactivate the focus switch for hours at a stretch. But art and life also need periods of diffuse attention to fuel creativity, taking us places we didn’t know existed. Without the aimless times, I’d never have thought to inquire into the brain states of zebrafish. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed