|

One pandemic day looks much like another. I track the calendar by weekly routines: Tuesday trash pickup, Wednesday laundry, Thursday groceries. Chores will remain in post-pandemic life, of course, but people and places and activities will reintroduce variety.

Rituals, like routines, can look the same from day to day. The difference is that rituals are infused with meaning and intention. Some writers begin their pen-to-paper or hand-to-keyboard time with a ritual to focus the mind: light a candle, or meditate, or sip coffee and watch the sun rise. “Meaningless ritual” is an oxymoron. Repetition without presence or meaning is merely routine. Any routine can be converted to ritual with mindfulness. Washing the dishes to wash the dishes. Feeling the warmth of clean towels as you fold. At the same time, I cherish the inclusion of mindless routines in the mix, activities so habitual that my thoughts can wander free. Being fully present is a wonderful thing. So, to me, is the unfocused state in which imagination runs rampant, untethered to the here and now.

2 Comments

For most of the past year, I figured coronavirus could do serious harm if I got infected, but avoiding people kept my exposure low. Last month, I traveled to a state where exposure was almost ubiquitous, trusting vaccination to minimize my risk.

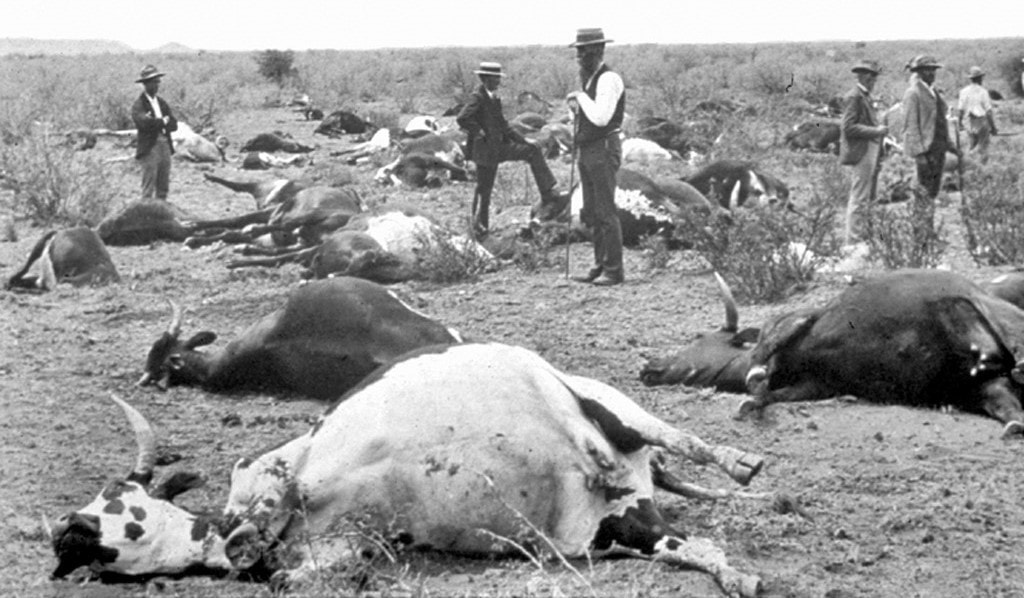

All our lives we weigh risks as a basis for decisions, large and small. I’ve long thought of risk as having two elements: how likely is something to happen, and how bad might it be if it does? Lately I’ve noticed a third major element: personal risk tolerance. As my sociologist father taught me long ago, statistics predict populations, not individuals. How much certainty does your spirit require? What is your comfort with the unknown? Data and logic go only so far. In the waning of the pandemic, some of my vaccinated friends remain outdoors in masks. Others dine in restaurants and hop on airplanes. There’s nothing wrong with letting emotions influence our choices. Without emotions, in fact, neuroscience suggests we couldn’t make decisions at all. Rinderpest, or cattle plague, devastated southern and eastern Africa in the 1890s. With a fatality rate near 100%, the bovine epidemic caused mass starvation among humans. Europe and Russia managed to eliminate the pestilence by the early 1900s through quarantine, hygiene, and slaughter. After development of a vaccine, rinderpest in 2011 became the second disease ever officially declared eradicated.

I was privileged some years ago to attend a meeting on disease eradication at The Carter Center in Atlanta. With smallpox eradicated by 1980, what other human diseases might be targets? As best I recall, criteria included that a disease be infectious, caused by a virus that would die out without human hosts, and preventable by vaccine. Covid-19 wouldn’t make the list; even if every human were immunized, coronavirus could lurk in other animals to come back later. Herd immunity is the way a mostly immune population forms a circle of protection around the susceptible few. It’s why unvaccinated babies and people with weak immune systems rarely get measles in the United States; the virus can't spread for lack of hosts. The threshold for herd immunity depends on too many factors to calculate precisely. How effective and long-lasting is the vaccine? How infectious is the virus? How carefully do people behave? How much do unvaccinated individuals cluster together, letting a single case set off an outbreak? Those factors for Covid are all changing or not fully known. Perhaps the best we will manage is control. Coronavirus may continue to circulate at low levels, mutating along the way. We may return year after year for the latest vaccine formulation, as many of us do for flu. Not the best of all possible worlds, but one we could live with. We may have to. If I thought of them at all, I thought of magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal and Good Housekeeping as light reading in a doctor’s waiting room, an occasional source of recipes. I never thought of them as Progressive Era forces for social reform, alongside the movements for prohibition and suffrage.

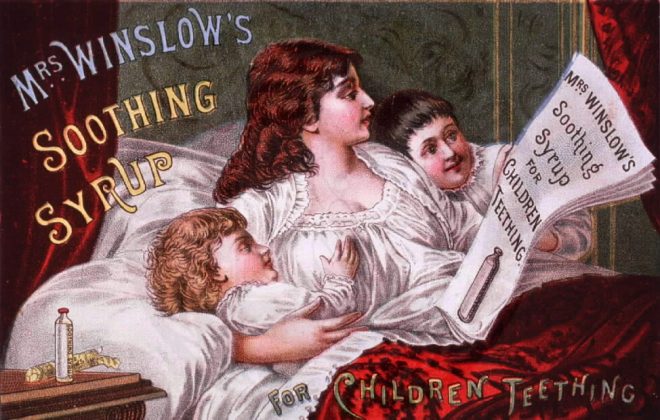

Middle-class women around 1900 organized to protect home and family. They battled corruption that threatened health, safety, and sanitation. Women’s magazines pioneered investigative journalism to inform and promote these efforts. Unscrupulous vendors peddled quack remedies promising to cure every ailment. In response, in 1892 the Ladies’ Home Journal became the first magazine to refuse medical advertising. It compelled Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup to reveal its ingredients and eliminate the morphine. The editor published the ingredients of other patent medicines and hired a journalist-lawyer to investigate abuses. Other periodicals followed suit, building public pressure to regulate drugs. No law required labeling the contents of packaged foods. Good Housekeeping published articles about hazardous food colorings and preservatives, such as formaldehyde in infant formula. It opened an experiment station in 1900 (later called the Good Housekeeping Institute) to test products and issue consumer alerts. The magazine campaigned for a national pure food law and advised readers how to add their voices. Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. Women’s magazines had been laying the groundwork for years. Grateful to be fully vaccinated, some of us are relearning the art of unmasked, face-to-face conversation. I hope this shift won’t breathe new life into low-tech tools for muting one another.

For example, “You’re in denial” uses classic psychobabble to silence disagreement. If you answer, “No, I’m not,” you just proved the speaker’s point. Another conversation-stopper is “Can’t you take a joke?” It shifts blame from one who says something offensive to the one who takes offense. Uneasy with threats to batter a spouse or kill an elected official? If you don’t want to be dismissed as humorless, better keep your mouth shut. “I’m just saying” is a more recent addition to the toolkit. It supposedly takes the sting out of a remark by labeling it casual opinion or observation. Rather than an invitation to explore, it signals lack of interest in analysis or debate. You are free to respond, but your response will fall on deaf ears. You’re on mute. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed