|

“O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!” - Robert Burns, “To a Louse” “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.” - Kurt Vonnegut, Mother Night Zoom still confuses me. In a group set on gallery view, if we all lean left with the right arm raised, the screen shows me leaning the opposite way from everyone else. Apparently Zoom shows me in mirror image and the rest as if they’re facing me in a photo. Which gives a truer picture, the mirror or the photograph? It’s human to care how others view us. This can reinforce community norms. On the other hand, it’s unhealthy to care too much. Aware and conscious may be synonyms, but self-awareness becomes a liability when it sinks into self-consciousness. Then there’s the fake persona, the image projected in order to disguise the true self. That’s great when Julie Andrews whistles a happy tune in The King and I to suppress her fear. Not so great when it’s you or me unable to establish honest ties. Some people seem to value image so highly it obliterates any separate sense of self. Nothing fake about it. Photo ops are all that matters. A recent mass shooter was said to have nurtured an idealized image of mass shooters online and shaped himself in that image. How do you want to be remembered? What do you want carved in your gravestone? Personally, I’d rather forget all that in favor of connecting with the individual in front of me. How others see me is their business.

0 Comments

Eating sweet, juicy blackberries straight off the vine was an unexpected pleasure of last week’s Ice Age Trail segment behind a golf course. Thorns were the downside. Even when I resisted reaching in for another berry, branches blocking the path scratched my bare skin. I could have stayed home to weed, but then I’d have missed the walk. It’s all trade-offs.

Whether a decision is weighty or trivial, personal or global, moral or strategic, every option has pros and cons. Without costs or silver linings, there’s no choice to make. What to do is obvious. In these contentious times, it can be hard to admit there’s right and wrong on both sides of the issues we debate so hotly. To acknowledge trade-offs doesn’t betray our deep convictions. Instead, it opens us to the humanity of those with whom we disagree. We may find similar pros and cons on their scales and ours. Sometimes we just weigh them differently. How did our Founders view abortion when they wrote the Constitution? I doubt they gave it much thought. Morning sickness and lack of monthly bleeding were female ailments, best left to wives and midwives. How carnal knowledge related to childbirth was a mystery. The first sign of growth in the womb came at four or five months with “quickening,” when the mother felt the baby move. Perhaps that’s when a piece of the mother’s body broke free or the male seed sprouted. Perhaps disrupted cycles cracked the shells in which babies had waited since Creation, nested inside each other like a Russian doll.

As in British common law, ending a pregnancy or “restoring the menses” was legal in America before quickening but not afterward. It was often done with herbs or patent medicines, and was most common among married, middle- or upper-class white Protestant women. Disapproval was reserved for unmarried women and Catholics, guilty of sex outside wedlock or for purposes other than procreation. The American Medical Association, founded in 1847, campaigned to prohibit ending a pregnancy before quickening. Why? Some say it was to protect women from poison by unregulated abortifacients; or to wrest control of women’s health from midwives; or to counter the declining white Protestant birthrate in reaction to rising immigration. By 1880, all states had laws to restrict abortion. The science of conception was still unfolding; DNA lay decades in the future. Laws against abortion, like those on contraception, were more about public morals than what was happening in the womb. Does it matter what the Founders believed? Would they have thought differently if they knew what science later revealed? Should a notion of long legal tradition give more weight to the laws of 1820 or 1880? These are questions of public policy and judicial interpretation, not my sphere today. I’ll only say, if the cultural and legal history of abortion has a role in the discussion, let’s at least get the history right. The cultural and political divisions of our time look as nearly impassible as the snow-covered peaks of the Continental Divide, back before railroads and airplanes. Other great North American drainage divides offer more inviting models. The one I know best separates the watershed of the Lakes/St. Lawrence River from that of the Mississippi River. Waters on one side flow to the North Atlantic; on the other, to the Gulf of Mexico.

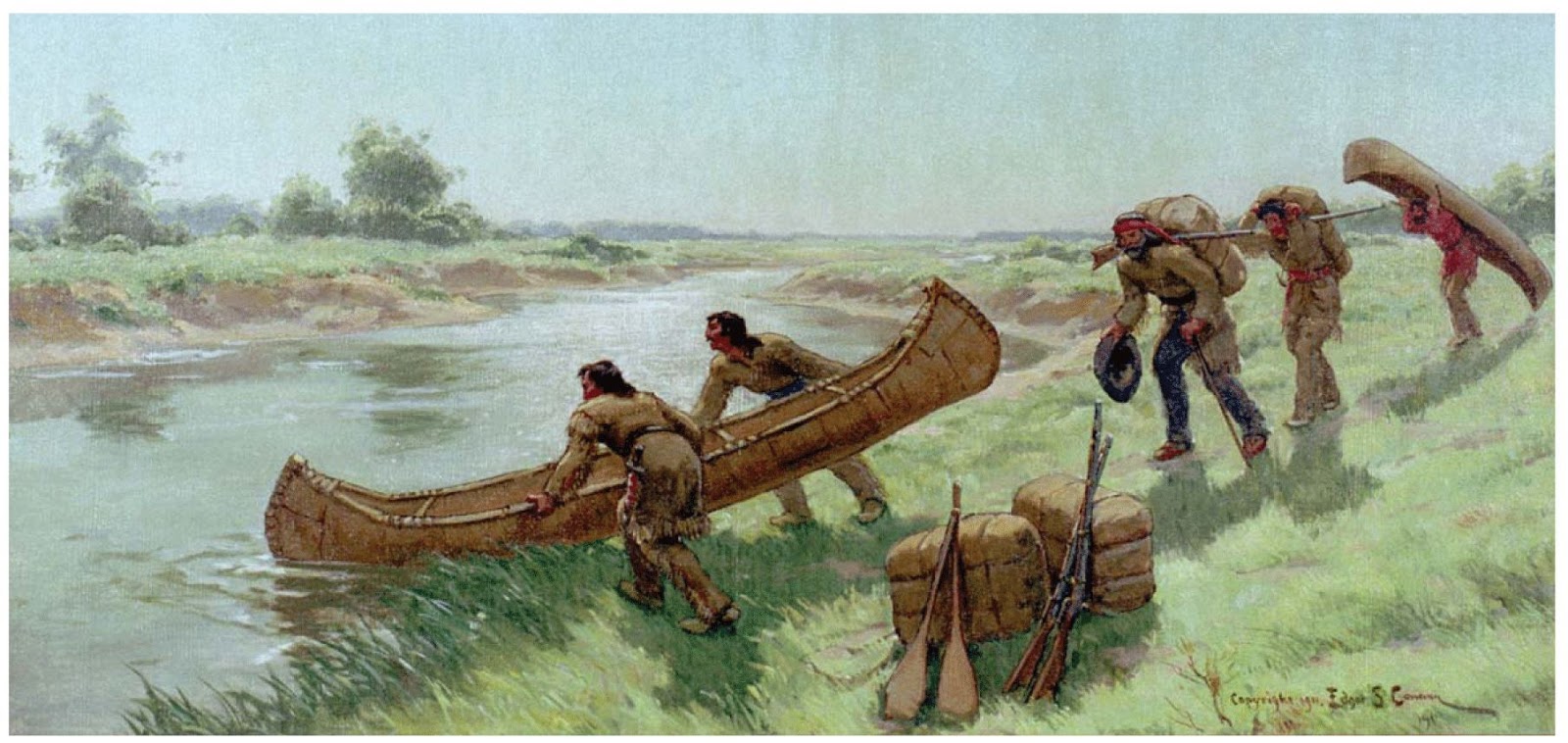

This divide looks far from dramatic. It is low, often marshy, and scarcely visible to the casual observer. Centuries ago, before canals, spring rains made some marshes wet enough to paddle across. Otherwise, travelers had to carry goods and canoes overland from one watershed to the other. French fur traders called such crossings portages, from French for “carry.” Major portages connected Green Bay with the Wisconsin River, Chicago with the Illinois River, and Cleveland with the Ohio River. To cross them was tiring but not prohibitive. The Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Gulf of Mexico are two thousand miles apart. That’s a plausible metaphor for today’s societal distance between right and left, conservative and progressive, red state and blue state. We’ll never all think alike, and it wouldn’t be healthy if we did. But the barrier shouldn’t have to consist of impenetrable mountains. What if we envisioned it as low and possible to traverse? Might we aspire to connect despite differences, and some days even to paddle across? Image: The Chicago Portage by Edgar Spier Cameron, 1862-1944. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed