|

Fear helps us survive. It sharpens our awareness of potential threats and prepares us to fight or flee. If reckless teens seek out the adrenalin rush, more of us imagine threats at every turn. Overdone, the survival trait no longer serves us.

Halloween is a time to build tolerance for the scary we know to be safe. Horror movies do the same, though I avoid them. Susceptibility varies by nature, nurture, and age. The three-year-old frightened by Where the Wild Things Are will love the book at four. Nerve and resilience grow through controlled doses of exposure to a false threat, whether it’s new technologies (my bugaboo) or singing in public. “You gain strength, courage, and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face,” Eleanor Roosevelt said. What better place to start than with masked strangers at the door demanding treats? Photo by tracy ducasse.

3 Comments

I cleared six-inch-high piles of papers off my desk. Some of the morass should have been tossed a year ago. One note was dated 2020. Admiring the nearly bare surface called to mind the phrase, “Draining the swamp.” For centuries people have drained marshes and swamps, sometimes to create solid ground for road construction or farming, sometimes to eliminate breeding places for disease-bearing insects.

In 1912 the socialist Victor Berger wrote, “We should have to drain the swamp—change the capitalist system—if we want to get rid of those mosquitos.” The next year, labor leader Mother Jones said of the bosses-vs-labor industrial system, “Let’s kill the virulent mosquito and then find and drain the swamp in which he breeds.” Politicians of both parties since the 1980s have used the metaphor variously to mean bureaucracy, lobbyists, corruption, terrorism, regulation, or government waste. Nothing noxious was breeding in the piles on my desk; that better describes a basement or refrigerator full of mold. My mess was, however, an impediment to fresh projects, the way literal swamps are impediments to agriculture or roads. And if the paper piles build up again, I could rework the metaphor to play on how swamps promote wildlife and safe weather. I’ve begun watching a lecture series on the Spanish Civil War. Though Spain in the 1930s had many distinctive aspects, some broader factors hold warning for the United States today.

Many Spaniards accepted the republican constitution of 1931 only so long as it served their objectives: secularization and land redistribution on one side, property rights and the Catholic Church on the other. Democracies work only if the majority respect their constitutions unconditionally. Playing by the rules matters more than any policy agenda. Responding to losses with “Not my president” or election denialism undermines democracy. In the early 1930s, political opinions in Spain ranged over a broad spectrum. Only a small minority admired Stalin on the left or Mussolini on the right. When the attempted military coup of 1336 triggered a brutal civil war, everyone had to choose sides. Violence breeds polarization and empowers the fringe. Never have I seen more condoning of political violence in the U.S. than in the past few years. As the two sides became increasingly identified with their extremes, what might once have been preferences or perspectives turned into moral imperatives. Combatants demonized their opponents. The non-negotiable defense of the Church or the working class excused any atrocity. Dehumanization rejects any outcome except total victory. After the rebels won in 1939, Francisco Franco ruled Spain as dictator until his death in 1975. I hope the United States still has time to learn from Spain’s example. Image: Bridge at Ronda, Spain. During the civil war, right-wing Nationalists allegedly threw left-wing Republicans to their deaths from the bridge. Parents, teachers, role models, and peers were the great personal influences of my youth. Among the many I never met were authors, journalists, celebrities, and occasional politicians. When did influences become influencers, and what changed along with the word?

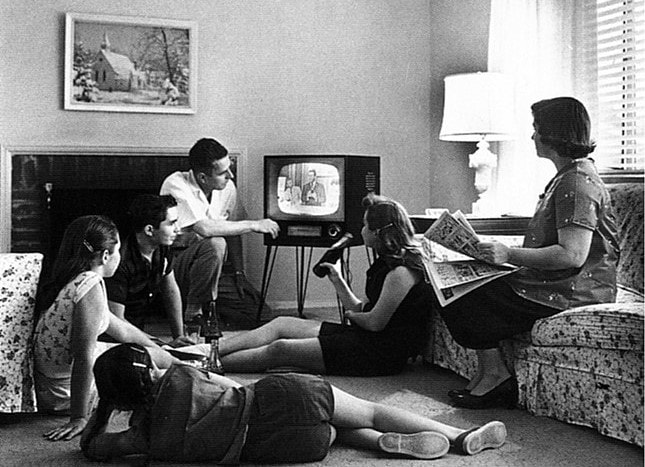

An influencer is someone with a large social media following who contracts to promote brands and products for profit. According to dictionary.com, this use of the word became widespread from about 2015. Far more than old-time television or billboards, social media make it possible to target large numbers in a precise niche. Influencers build a niche for the purpose of advertising other people’s products. Whoever grew up thinking, “I want to be a basketball star so I can make big money selling shoes?” Whereas traditional celebrity endorsements were an option for athletes and actors at or past the peak of their careers, young people today hope to become influencers to build their careers. A study a few years back found the notion of being a social media influencer appealed to 86 percent of participants age 13 to 38. The whole idea feels bizarre to me. I must be getting old. Image: The old media. Evert F. Baumgardner, family watching television, c. 1958, National Archives and Records Administration. As a child, long before I guessed family members would someday live somewhere in Africa, the continent intrigued me. Maybe it was from reading The Little Prince, set in the Sahara. Maybe it was from its size on our household globe, much of it labeled “French West Africa.” Picture books depicted Africa as a country like Mexico or Poland.

In recent adult conversations and study groups, I hear shock at role of Africans as sellers in the transatlantic slave trade. The white slavers who created the cruel market rarely captured human “cargo” by themselves. Africans were complicit. How could they have sold their own people into slavery? Who are “your own people”? No one expects people of India or China to identify primarily as Asian. No one seems aghast that France and Germany fought each other even though both are European. Africa in the heyday of the slave trade comprised dozens of nationalities such as the Yoruba, Bakongo, or Fulani. “Their own people” would be those of the same ethnicity. The idea of “Africa” scarcely existed. Pan-Africanism took shape only much later, outside Africa, among descendants of enslaved workers torn from their ethnic roots. Image: Africa from space. NASA.www.nasa.gov/image-feature/africa-and-europe-from-a-million-miles-away |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed