|

My mother said choosing birthday and holiday gifts for me was easy. Unlike family members who lived mostly in their heads, I liked things.

Me, materialistic? I never shop just for the fun of it. I wear clothes till they’re full of holes. But I've come to admit my mother was right. I like many things for the personal meanings they hold. Mugs made by my Aunt Eileen, founder of the Potters’ Club (now Visual Arts Centre) in Montreal. Carved owls from visits to San Antonio and Greece, and an owl pendant from my spouse, celebrations of the barred owl that hoots in our woods. A high shelf in our living room holds my grandmother’s best doll, Ila; my mother’s best doll, Dorothy; and my best doll, Carol. I treasure the sense of connection back through generations of girlhood. Acquiring a brand-new trio of exquisite dolls holds no appeal. Stuff is still in boxes in the basement from packing up my parents’ house after they died. I've never unpacked my parents’ ornate 1930s wedding plates, which I keep because my father asked me to. One friend in the midst of closing up her mother’s home commented that you can pass along things, but you can’t always pass along meanings.

6 Comments

Last week I attended two unrelated meetings where participants were invited to share views on a given topic. For a time, no one spoke. After one person broke the emptiness, silence fell again. Were others as uncomfortable as I was? Were they bored, or planning the rest of their day, or struggling to answer the question posed?

I’m more accustomed to rapid-fire discussions filled with interruptions. Part of it is cultural; long pauses between speakers are standard among the Navajo. For me, interrupting is also a relic of childhood when, as the youngest in the family, I feared I'd never get a turn if I waited for the rest to stop talking first. Zoom helps, with its “mute/unmute” and “raise hand” features and the impossibility of hearing two voices at once. I’m trying to use the silences to learn to listen more deeply, breathe more slowly, and be more fully present. It’s a work in progress. We visited downtown Madison last week after a while away. Our traditional record store, toy store, and lunch spots are long gone. At the campus end of State Street, high-rise apartments have replaced the restaurants Husnus and Kabul. It isn’t like it used to be.

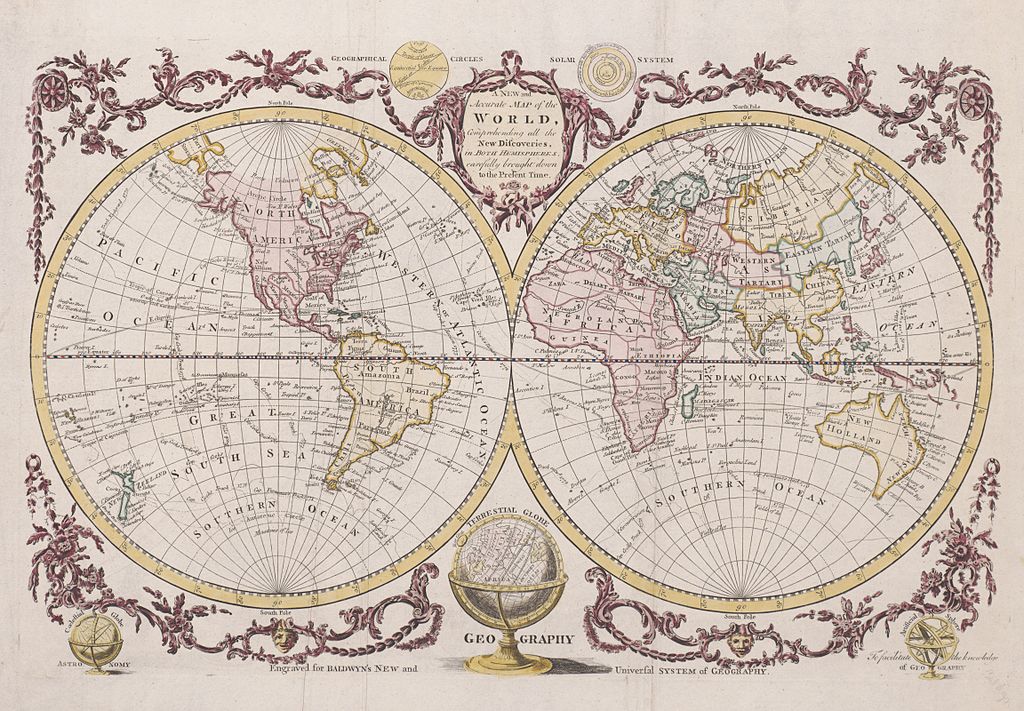

In happy childhood memories, I’m playing in the giant wasteland behind the family's modest backyard. Now a deep, manicured lawn meets that of its back-to-back neighbor the next street over, separated only by a white picket fence. I miss the overgrown playland. It’s not the way it was. Does one picture a favorite place as enduring before one met it and for months or years thereafter? Were its imperfections part of its charm? Does novelty feel like betrayal? Maybe students like to live in high-rises; maybe kids enjoy playing in big, tidy yards. These may be the memories they’ll cherish. We love places not just for their traits but for the memories we attach to them: exuberant youth or young adulthood, romance, healing, you name it. Change is the only constant, but the constancy of memory tugs at our hearts. Ages ago, most people subsisted on farming, herding, or fishing. Here and there, empires arose and fell. Europe didn't particularly stand out. So why did Europeans by the 1800s dominate much of the world?

Proposed explanations intrigue me. Among those I've read:

|

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed