|

It ranks with “unprecedented” and “you’re muted” to conjure up the past year or two. When have we seen so much outrage in so many spheres of public life? Party A, outraged, declares Party B’s words or deeds an outrage and responds in a way that outrages Party B. It’s an outrage perpetual motion machine.

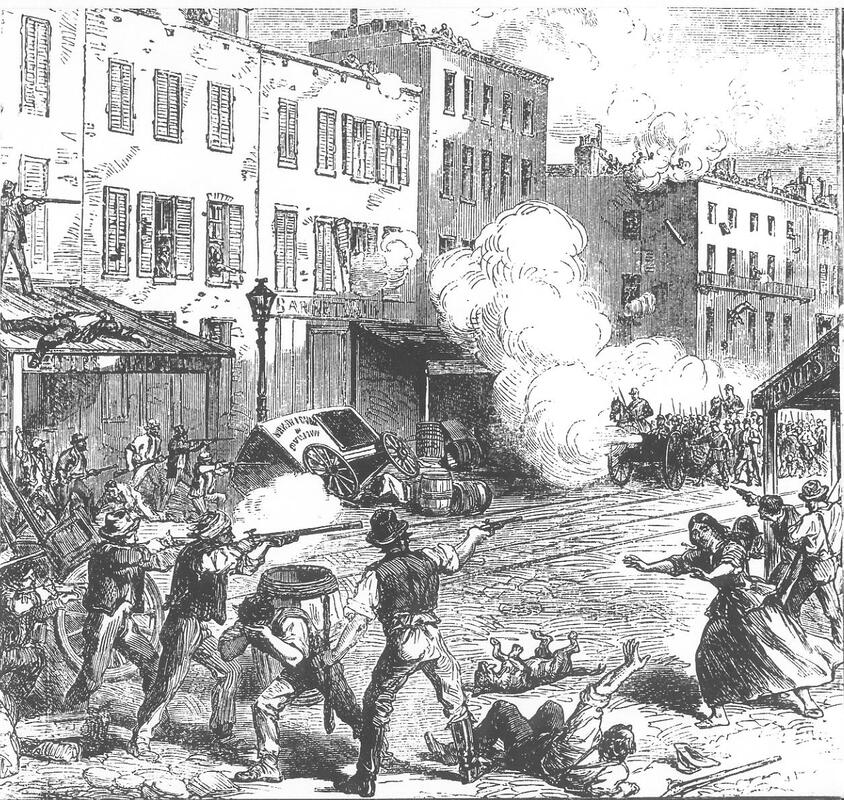

Originally unrelated to rage, the word outrage comes from Latin ultra (“beyond”). An outrageous act goes beyond acceptable bounds. The outraged seek allies. Their righteous anger is contagious. What makes a feeling of outrage so addictive? Is it the rush of adrenalin, the ego-boost of moral certitude, the sense of belonging in a group bound by shared passion? I don’t personally enjoy it, so I can only guess. At its best, outrage generates action to right a grave injustice. Some exploit it to increase ratings or social media "likes." Among its dangers is a moral absolutism that wipes out any sense of proportion. To be certain of one’s innocence leaves no room for humility. Opponents seem scarcely human. Having God on your side makes any compromise a deal with the Devil. Image: New York City draft riots of 1863.

6 Comments

Cleaning protocols are all the rage these days. “Cleanliness is next to godliness,” John Wesley preached in the late 1700s. The idea is much older, fusing moral purity with ancient taboos rooted in noticing what made people sick. That said, we all have distinct scents unrelated to health or godliness. Just ask a dog.

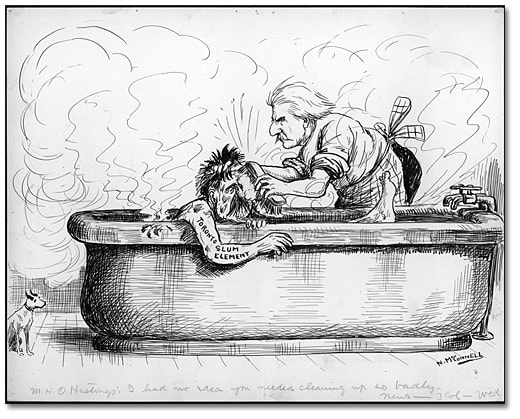

We can’t smell our ordinary selves; we habituate too quickly. Neither could our less-scrubbed ancestors. To ask whether they stank is like asking whether a falling tree makes a noise if no one hears it. Human noses then as now were attuned to difference, such as the warning stench of a sickroom or rotten meat. Street urchins and swineherds could smell each other but not themselves. Our ancestors varied by culture, of course. Vikings bathed weekly and washed face and hands every day. European townsfolk frequented public baths until the arrival of the plague, when it became safer to stay dirty. Ancient Roman aristocrats used not only communal baths but lots of perfumes. I know less about the traditions of Africa, Asia, or the precolonial Americas. Diet alone could give any culture a distinctive aroma noticeable only to outsiders. For elitists, xenophobes, and purveyors of deodorant, difference was and is the point. A sweet scent wasn’t about health or virtue, but the luxury of not having to work up a sweat. Distinctive cooking smells helped scapegoat immigrants and foreigners as dirty sources of infection. Showering daily may not make us any healthier than the ancestors who labored six days and bathed on the seventh, but it sells more soap. Image: Archives of Ontario, c. 1910-14. The year I lived in Africa long ago, we didn’t worry much about malaria. Mosquitoes that carried the parasite didn’t thrive on the cool, dry Eritrean plateau, 7200 feet above sea level. For rare jaunts to lower altitudes, we swallowed malaria pills before, during, and after—probably chloroquine, though I don’t remember for certain.

Deadly malaria evolved millions of years ago and spread to every inhabited continent. Controlling it in the United States was CDC’s original mission in 1946; the agency was based in Atlanta because most of the nation’s malaria was in the Southeast. CDC’s program centered on spraying home interiors with DDT. Encouraged by its success, the World Health Organization in 1955 undertook to eradicate the disease worldwide. When I worked for Rotary on polio immunization in the 1980s, malaria killed perhaps a million people a year. In debates whether polio could be eradicated, advocates pointed to the recent eradication of smallpox as reason for hope. Naysayers pointed to WHO’s inability to eradicate malaria globally. The disease still kills more than 400,000 people annually, mostly in Africa, mostly young children. WHO last week recommended a broad rollout of the world’s first malaria vaccine, developed by GlaxoSmithKline and oddly named RTS,S. The world’s first-ever vaccine against any parasitic illness, RTS,S is far from ideal. It requires a series of four injections. Efficacy is only 30 to 40 percent. Nevertheless, in combination with bed nets and antimalarial drugs, it should save tens of thousands of lives each year. Now that’s something to celebrate. “There lives more faith in honest doubt,

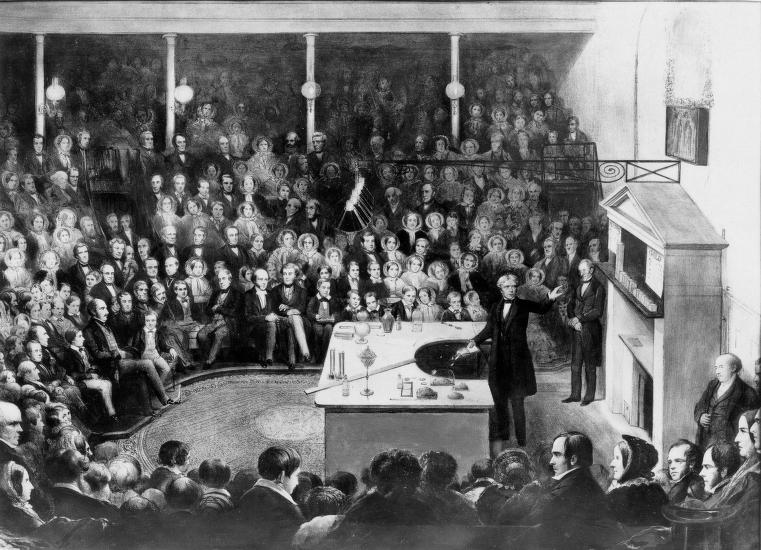

Believe me, than in half the creeds.” - Alfred, Lord Tennyson Questions aren’t welcome to those in authority. Churches and totalitarian regimes have imprisoned or killed people who voice honest doubts. My sympathies are largely with the questioners, who challenge blind obedience and inspire fresh discoveries. The past year has me wondering, is there a point when questioning should stop? The temptation is to say yes, stop when the questions turn dangerous. But danger has always been the excuse for burning heretics and cracking down on dissidents. How is danger to public health or trust in elections so different from danger to eternal salvation or national survival in time of crisis? Why do unending questions bother me in some cases and not others? The relevant distinction, to me, is between questions in pursuit of truth and pseudo-questions to hold truth at bay. My sympathy is for questioners motivated by curiosity and a search for answers, questioners open to possibility and fresh insights. I have none for those who ask, “Isn’t the earth really flat?” again and again, indifferent to evidence. Who promote public distrust, then use that distrust to call the round earth hypothesis an open question. Who will insist the question remains open until someone proves the earth is flat. Questioners in search of answers have my sympathy, whether or not I share their honest doubt. Dishonest doubters are a different matter. They disguise denial as uncertainty and immovable stances as questions, simply because they don’t like the answers. Image: "Why does the ice float?” scientist Michael Faraday asked in one of his Christmas lectures. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed