|

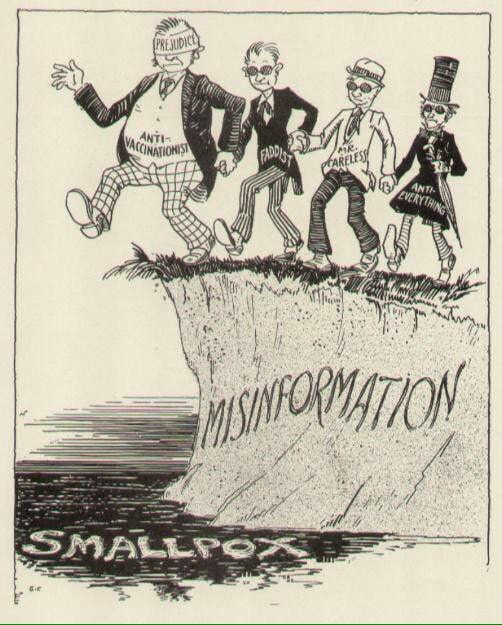

Required reading in my grad school history program included Richard Hofstadter’s Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963), which tracked a long national history of celebrating ignorance. Second-guessing the experts began long before the Internet.

Are egos too fragile to admit ignorance or error? Three thoughts make it easy on the ego to acknowledge how much I don’t know: 1. I know more about some things than others. Thank goodness the contractors who fix our leaks and outages know what they’re doing. Equality doesn’t mean we’re equal at everything. 2. I’m teachable. In my areas of strength, there’s always more to learn. When the facts contradict what I thought I knew, they bring an opportunity to grow. 3. I’m curious. Ignorance can lead in either direction, to ask questions or to think we have all the answers. When we choose to open up rather than close down, we welcome those who have the expertise to answer our questions.

4 Comments

We each see world events through a lens of personal experience and concerns. Along with fear and sorrow for the Afghan people, I look at last week’s collapse through lenses of geography and history: an impoverished, almost impenetrable mountain region at a crossroads of ancient civilizations, repeatedly invaded, never brought under control. I also see it through the lens of polio eradication.

Endemic polio has paralyzed only two children so far this year, one each in Afghanistan and Pakistan, both in January. The Taliban doesn’t object to vaccination on principle, though local leaders vary. Instead, top leadership suspects house-to-house campaigns of being Western spy operations to help target drone strikes. And many believe scarce jobs as vaccinators should go exclusively to men, though a mother at home with her children may open her door only to a woman. I can’t predict what the final Taliban takeover will mean for protecting children from polio. The dangers are real. Still, an end to decades of hostilities might increase security for families and health workers. Cessation of drone strikes could gradually ease suspicion. On the polio front, the present crisis may offer glimmers of hope. See Science writer Leslie Roberts for more. Image: Child in Afghanistan receives polio vaccine (UNICEF file photo) Wildfires, conspiracy theories, and viral variants are raging out of control. Not that we ever held power over the universe, but don’t we remember once feeling we had a voice in it?

As the youngest in a smart and strong-willed family, I grew up with no illusion of control. Some friends and family members find me controlling all the same. Like many of us, I’m probably a bundle of contradictions. Writing and (I suspect) other creative arts abound in contradictions about control. They require not only technical mastery, but also space for unpredictable flow. Fictional characters don’t always follow an author’s orders; they have their own ideas for what to do or say. Try to control too much and the result is formulaic and flat. Too little, and the result is often incoherent. Either extreme can prevent ever finishing, the over-controller stymied by perfectionism and the under-controller continually distracted. The same may hold in the arts of politics and of everyday life. To hold on and hold loosely is an art in itself. It is mid-afternoon, and all the sunflowers are facing east. The farmer says this year has been so dry, the plants conserve scarce energy by not turning to face the sun.

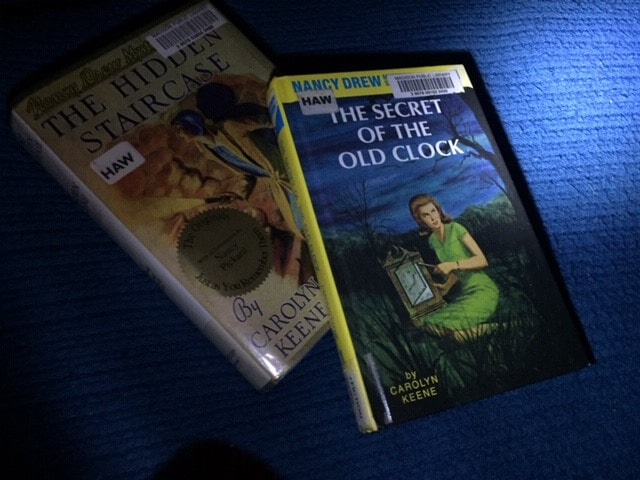

The same farmer is taking his parents this week to the Wisconsin State Fair to receive a Sesquicentennial Farm Award; their farm has been in the family for 150 years. Family farms still exist hereabouts. Some supplement dwindling agricultural income by offering hayrides, corn mazes, pick-your-own berry patches, off-season boat and RV storage, snowplow and landscaping services, or car detailing in an old barn. After months of national and personal crises, many people are feeling resources stretched thin. Resilience is down. There’s a dearth of emotional vitality. What do sunflowers and family farmers model for how to keep going when we start to run dry? Conserve energy with a break from a practice you normally did. Try something new with resources you already have. Hold on to what’s essential and add or subtract around the edges. Last week I read my first-ever Nancy Drew mystery. It seemed time to meet the girl whose courage and wits had influenced countless women I admire. Though I heard of her in my teens, I was a Sherlock Holmes snob; why bother with lesser sleuths?

The authors I relished back then, like Louisa May Alcott and Laura Ingalls Wilder, transported my imagination into a different time or place. Only later did I get hooked on murder mysteries as a genre. Along with the fun of solving a puzzle, many took me to unfamiliar worlds like Tony Hillerman’s Navajo country or Dana Stabenow’s Alaskan Bush. My advisor at Oberlin College, Marcia Colish, told me mystery novels were favorite leisure reading among her historian friends. It’s no coincidence. Like mysteries, historical research is a process of finding and assembling seemingly disparate clues into a coherent narrative. Smart, brave women detectives with a passion for justice abound on library shelves today. I may not devour the rest of the 56 Nancy Drew titles, churned out between 1930 and 1979 by a series of ghostwriters for the same publisher as gave us the Hardy Boys, Tom Swift, and the Bobbsey Twins. The writing can grate. (“I’ve found it at last!” she thought excitedly.) But no matter. In a culture that taught girls to be timid and hide their brains, Nancy Drew showed a generation of young readers another possibility. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed