|

Elders for millennia have complained about the younger generation. Surveys since 1949 confirm that in every decade, people around the world believe kindness and morals have declined—even though their evaluation of kindness and morals at the time of the surveys stays much the same from decade to decade.

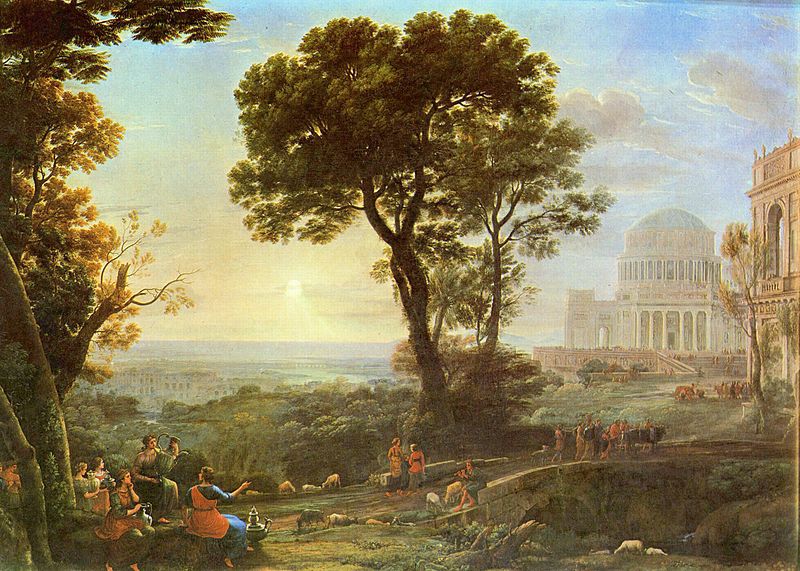

The conviction that things are getting worse seems rooted in human nature more than objective decline. Some are nostalgic for the calm, trust, and family values of the 1950s. Others are nostalgic for the activism and sense of purpose of the 1960s. Many traditions speak of a past golden age: the Garden of Eden before the expulsion, matriarchal Crete before conquest by patriarchal Greeks, or harmony with nature before industrial capitalism. Two biases shape our perception of decline, psychologist Adam Mastroianni suggests. We focus on the negative to alert us to dangers in the moment, as do the media drawn by sales and ratings. As for the past, Mastroianni says the pain of bad times fades faster than the joy of good times. I recall childhood tears as well as fun, but it’s the memories of fun that I dwell on. Visions of a utopian future are widespread, too. Legends predicted King Arthur’s return some day to save Britain in its hour of need. Zoroastrians believe good will defeat evil at the end of time and restore the once-perfect world. In a Christian hymn, “These things shall be: a loftier race than e’er the world hath known shall rise . . . They shall be gentle, brave, and strong . . when all the earth is paradise.” Hard times are like the baloney sandwiched between nostalgia and hope. That’s probably not going to change; it’s in our nature. Knowing so may at least add perspective. Image: A golden age of the past. Claude Lorrain (1604/05-1682), Vedute von Delphi mit einer Opferprozession [“View of Delphi with a sacrificial procession”].

0 Comments

Why am I caught up in the Wagner Group drama? I love a gripping tale. Besides, I share the cultural fascination with groups that operate outside the law, provided they’re long ago and far away. It’s easy vicariously to relish the supposed freedom and adventure of old-time pirates, train robbers, and freelance fighters on horseback.

Freelance is a term from early-1800s Romanticism to mean medieval mounted warriors who fought for profit rather than loyalty to lord or country. We freelance writers will recognize the trade-off between security and independence. Mercenary is much older, from Latin for “hireling.” Soldier of fortune is another classic term for one who fights in other people’s wars, motivated by pay not patriotism. Long ago and far away? Hardly. Much as the line between legal privateers and illegal pirates in Elizabethan England was a thin one, only a thin line distinguishes some “private security companies” from mercenaries. Remember Blackwater Security Consulting in Iraq, responsible for many civilian deaths? It’s one of many, from Mali to Syria, Sudan to Indonesia. “Business is booming,” Sean McFate of the National Defense University wrote in 2019. As best I can find, neither the U.S. nor Russia has signed the United Nations convention to forbid outsourcing warfare to mercenaries. The attractions are too great. The contracting nations get plausible deniability. Their contractors get a lack of accountability. It’s win/win for them, if not for anyone else. Image: From Paulus Hector Mair, De arte athletica II, 16th century. Years ago, a driving vacation brought us to the charming village of Lytton, on the Fraser River in southern British Columbia. It was named for Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873), British colonial secretary and author of the much-mocked line, “It was a dark and stormy night.” We’d lunched earlier at Lillooet, where our waitress was almost in tears over wildlife dying in a nearby forest fire.

After a harrowing drive from Lillooet to Lytton, mountains on one side and river on the other, with a blind curve where rockfall blocked half the road, it was a relief to park in Lytton and get out of the car. Smoke and flames were visible across the Fraser. We watched with fascination as firefighting helicopters lowered huge buckets into the river, then flew back over the forest to pour water on the blaze. Last week I learned for the first time that wildfire two years ago destroyed 90 percent of the village. Was I not paying attention, or does the American press ignore Canadian villages? Lytton is no more. Rebuilding is planned but hasn’t yet begun. Air quality health warnings keep many Wisconsinites indoors lately to avoid smoke from wildfires in northern Quebec. Distressing for us, it has to be immeasurably worse for residents evacuated from the path of the fires. Although Lytton is farther away, reading belatedly of the almost-total destruction of a village I’ve visited brings Canadian wildfires up close and personal. Images: (left) wildfire in Yellowstone 2013; (right) welcome to the “hot spot.” The images I found from the Lytton fire are copyright news photos. I attended Oberlin College on scholarship, from a West Virginia high school with excellent teachers but no exotic courses. To make room for me, someone with a fancier transcript from a classy suburb may have lost out. Unfortunately, admission to a specific college or getting hired for a specific job can be a zero-sum game. To choose among promising applicants, what’s “fair”? Fairness at Oberlin meant encouraging student interaction across diverse backgrounds, preparing us to contribute in a changing world. Fairness at another college might mean favoring the children of alumni and corporate CEOs, preparing them to replicate the past.

Replication is a factor in cutting-edge technology, too. Automated help systems are great, so long as my question is one many people have asked before. A chatbot can fake being you by mimicking language patterns and content from the past. You’ll need to write your own essay if you want to say something new. I love to study the past. I want to learn from it and build on it. Creative innovation benefits from established procedures and guidelines. Scientific method enables new discoveries and a way to distinguish them from fads. A written constitution allows for interpretation and amendment while constraining the sway of the mob. Fairness doesn’t have to require systems that merely replicate the past. A week and a half ago, Russia seemed on the verge of civil war. The brutal, Russian-funded mercenary Wagner Group, led by oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin, advanced on Moscow to demand a change in military leadership. Watching crowds cheer the Wagner Group fighters, I confess to shadenfreude. Chaos might take Russian heat off Ukraine. Prigozhin might replace Putin’s generals. But would that really be better?

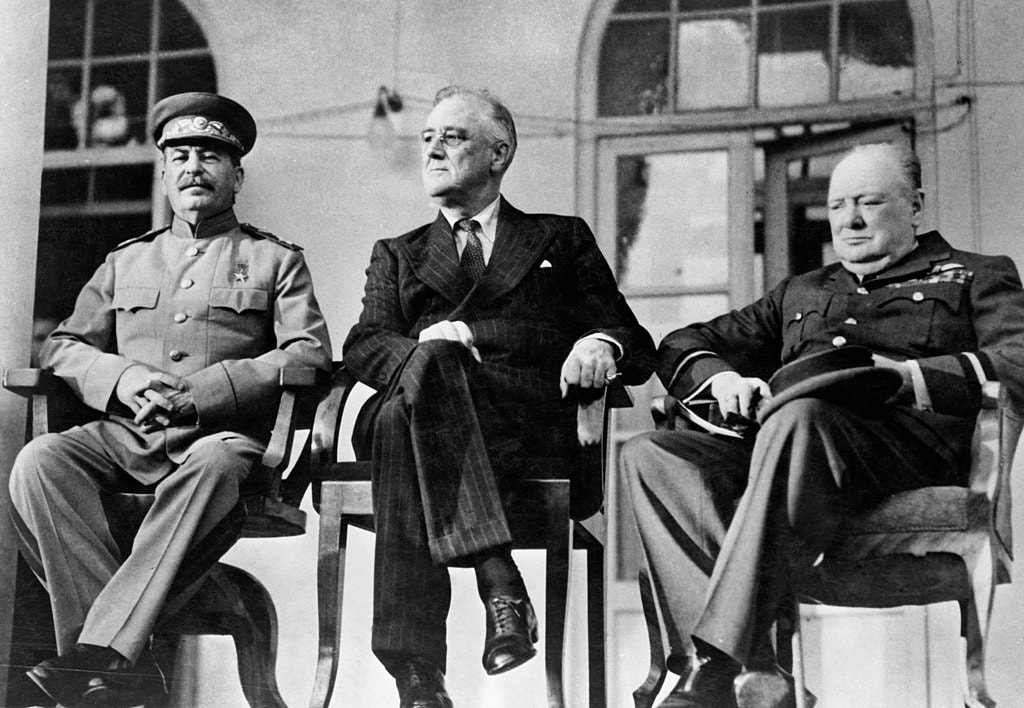

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” and “Politics makes strange bedfellows.” Though a U.S./Soviet alliance in World War II was essential to defeat Hitler’s Germany, it ushered in a half century of Cold War. The U.S. intervened in other countries’ affairs to protect or install authoritarian dictators. They shared our enmity toward Communism. What’s my point? First, don’t confuse situational allies with the good guys. Some are, some aren’t. I sometimes wonder if we underestimated Russia’s imperial ambitions after 1991 because at least it wasn't Communist. Second, reconsider what counts as an enemy. Immediate threats to our nation used to bring Americans together. Imagining coming together around such threats as pandemics, poverty, and bigotry. Our allies against enemies like these might truly become our friends. Image: Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (left to right) at the Teheran Conference, 1943. (Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-32833.) |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed