|

Another year is almost gone. We entered it with such relief at putting 2020 behind us. Instead, 2021 has brought crisis after crisis, from insurrection to Omicron.

Are we living in the dark times between two periods of joy? It’s an archetypal pattern: the malaise between nostalgia and hope, the trials between “once upon a time” and “happily ever after,” the Dark Ages between the Roman Empire and the Renaissance, the sinful world between Eden and the Second Coming. We humans evolved to see patterns whether or not they exist. They help us make meaning and, sometimes, notice causal connections. They can also entice us to put too much trust in our predictions. History does indeed repeat itself, at least in broad patterns. With the entire recorded human past to draw on, a diligent search can uncover examples of nearly any pattern you choose. For every trauma between two golden ages, you can find an era of new optimism between two traumas: Reconstruction before Jim Crow, the French Revolution before the Terror, the early years of independence for former African colonies and former Soviet republics before some fell into chaos. Choose your patterns with care. They may make the difference between despair and hope.

0 Comments

With its northern pine forests and immigrant German heritage, my adoptive home state is among the top Christmas tree producers in the U.S. Hundreds of small, family-run tree farms here are thriving during the pandemic. Want a Covid-safe, outdoor activity near home? Cut your own tree. Supply chain disruptions? No, this season’s crop was planted years ago.

Christmas trees also hold a place in the history of Wisconsin transportation and industry. The wreck of the Rouse Simmons. The schooner Rouse Simmons made its last voyage each year in late fall, filled with Christmas trees from upper Michigan to sell in Chicago. On Nov. 23, 1912, the Two Rivers WI Lifesaving Station learned by phone of an approaching ship showing signs of distress. A powered lifeboat went out but found nothing. The Rouse Simmons lay at the bottom of Lake Michigan, complete with trees, crew, and lumberjacks who had hitched a ride home for the holidays. “Get the biggest aluminum tree you can find, Charlie Brown, maybe painted pink.” Demand soared after the Aluminum Specialty Company in Manitowoc WI introduced Evergleam Christmas trees in 1959. Their glistening foil needles seemed to fit the spirit of the burgeoning space age. The fad collapsed in the mid-1960s after Charlie Brown’s Christmas made them a symbol of commercialization. The story season is upon us. Once again, remotely or in person, we share beloved tales to help fend off the darkness. Ancient stories tell of lamps burning eight days and wise men following a star. Year after year, the Grinch’s heart grows three sizes larger, and Linus suggests the scraggly tree just needs a little love.

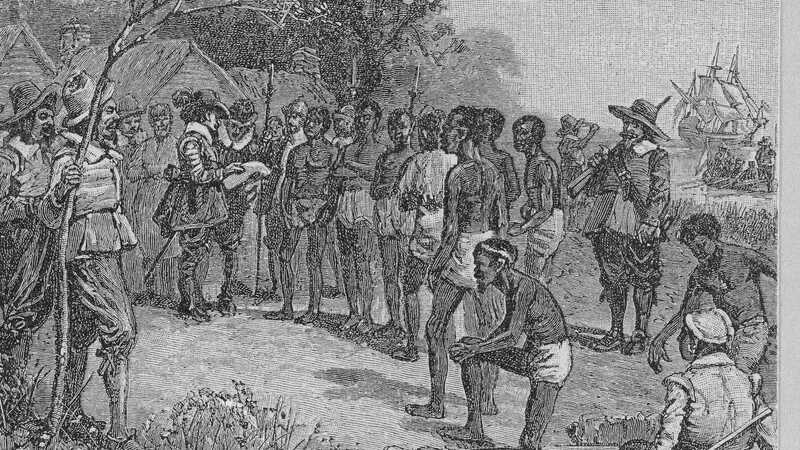

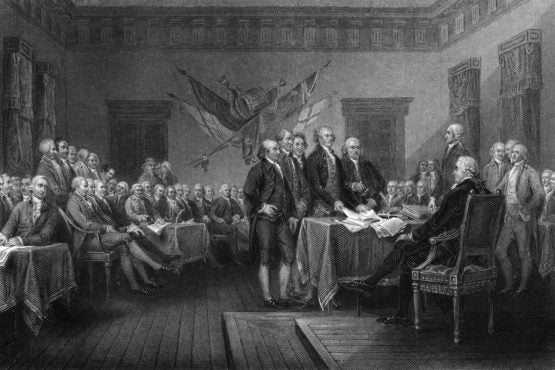

Stories grab our attention, engage the emotions, and stick in the memory more efficiently than dispassionate reasoning. They are quicker and easier to process. They prime us for the hormones to hug a child or run from danger. We evolved that way for survival. Our prehistoric ancestors used narrative to learn from each other's experience and pass that learning down through generations. Not all stories are equal. Some glorify violence, perpetuate false conspiracy theories, or widen the gap between ingroup and outgroup. When such a story comes up over the holiday table, citing data or logic alone won’t get you far. Consider responding to story with story. Your personal anecdote may not change minds either, but it might begin to open a heart. That’s how we are wired. Image: Sir John Everett Millais, The Boyhood of Raleigh, 1870. National Gallery. Walter Raleigh and his brother listen to an old sailor’s tales of adventure. Among the most contentious statements in the 1619 Project is in Nikole Hannah-Jones’s opening essay: “that the year 1619 is as important to the American story as 1776. That black Americans, as much as those men cast in alabaster in the nation’s capital, are this nation’s true ‘founding fathers.’” Critics commonly paraphrase this as claiming the American story really starts in 1619.

Stories begin where the storyteller begins them. Novelists may open with a dramatic incident, backstory, or a portrayal of ordinary life. Narrative historians, too, must choose where to start. It’s a question of focus and perspective, not fact. As the late Professor Geoff Blodgett taught us at Oberlin long ago, facts never speak for themselves. Even the most objective chronicler must decide which events to record and in what order. I have yet to see a United States history that begins on July 4, 1776, unless as a hook. In the “western civilization” approach of my school years, our national story started with the Enlightenment, or the Magna Carta, or even democracy in ancient Athens. More traditional accounts might begin with Columbus in 1492; more recent ones, with indigenous life before colonists came from Europe. The arrival of captive Africans in Jamestown in 1619 is as legitimate a starting point as any other. To argue whether it’s true or false is meaningless. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed