|

One advantage of cleaning house only occasionally is my housemates’ appreciation when it’s clean. If it were always pristine, no one would notice.

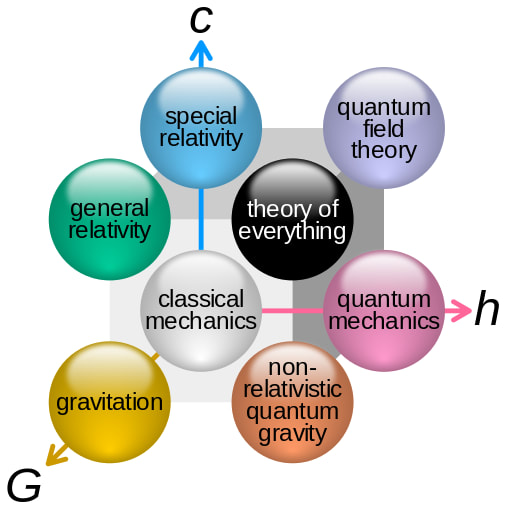

I’ve been watching a lecture series on particle physics for non-physicists. Segments involve relativity, which I struggle to grasp beyond the Newtonian basics. Relative to my house I’m sitting still at the computer, but relative to the sun I’m hurtling through space. My head is the same height relative to my feet, whether I stand on a creek bed or a mountaintop. Compared to other people’s suffering, my troubles are trivial. Can relativistic thinking ease my anxiety or grief? Not always. My peace shouldn’t depend on someone else’s pain. Sorrow isn’t a competition. Thinking I shouldn’t hurt, just because others hurt more, adds shame for feeling what I feel. Worse yet, telling people “Count your blessings” or “Others have it worse” trivializes their emotions. Yet in stressful times, when I acknowledge the stress and do what needs doing, one type of comparison keeps me going: then and now. I recall a long-ago time of feeling utterly helpless and alone. The point is not that I’ve been through worse, but that I’ve come through worse. I survived in the past; I can survive again. I’ll be all right, relatively speaking. Image: Cube of theoretical physics, drawn by CMG Lee.

4 Comments

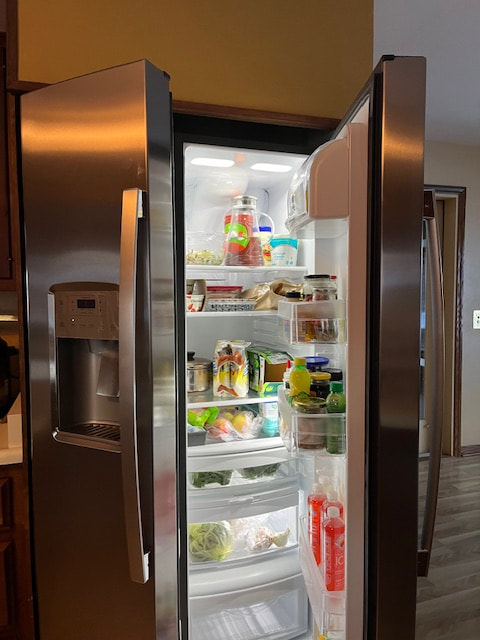

The refrigerator died. All the perishables that hadn’t already perished moved onto the wintry porch. The furnace went on the fritz. All our lap rugs and a space heater came into the living room. With fridge failing to cool and furnace failing to heat, I wished we could average the two for perfect comfort.

Even in the midst of trials and tribulations, I know the difference between crises of the present and those that matter in the long run. In my experience, a graph of personal troubles would not resemble a straight line or a bell-shaped curve so much as a two-humped camel. One hump includes missed flights, malfunctioning appliances, and troublesome calendar conflicts. They drive me to tears and then fade into memory. The other hump includes losses and traumas that change a life forever. They sink into the bones and may resurface years later, out of the blue. “How are you?” is a more complicated question than it sounds. For me, how I’m doing operates on two levels that don’t always match. The mood of the moment overlies a separate baseline for the year or the season. In a season of grief, I have sometimes—not always—laughed at a good romantic comedy. In a tranquil time of life like the present, losing the use of a refrigerator and a furnace in the same week stresses me out. No point fighting it. We feel what we feel. Below the stress, though, I try to remember that this too shall pass. Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp,

Or what's a heaven for? - Robert Browning, “Andrea del Sarto” Or a woman’s reach. What Barbie left me mulling has less to do with feminism or patriarchy than whether expectations of perfection boost or squash self-esteem. As a schoolgirl I brought home the happy news that I could be anything I wanted. My spoilsport father said it wasn’t true. Alas, he was right. Spectacular achievements take not only grit but some innate skill and some degree of luck. Not everyone who aspires to be an astronaut, a U.S. president, or an Olympic athlete will become one, no matter how hard she strives. Will she feel like a failure, as I did after an unsuccessful job search, or will role-playing with those Barbies inspire a healthy interest in science, politics, or sports? Some say perfection is excellence taken even further. I’d suggest the opposite. Perfectionism promotes limits. Don’t try new things you may do poorly. Stay within the safety of the known. Pursuit of excellence, on the other hand, opens a world of possibilities. Some will work out; others won’t. You win some; you lose some. Adventure. Explore. Ask questions. Admit your mistakes. You may not reach Mars or the Olympics, but you may discover places you never dreamed of—and have fun along the way. Photo: My grandmother’s, my mother’s, and my best dolls represented neither babies nor fashion models but girls a little older than ourselves. A cacophony of whistles and squeals drew me from the computer to my office window. A large, gray-brown fluffball rolled and tumbled in the dormant garden. It took me a moment to recognize it as a noisy pair of groundhogs, perhaps in the act of courtship or mating.

Groundhogs (aka woodchucks, of the squirrel family) are territorial and mostly solitary. From spring to fall we watch our resident groundhog Chuck dine on coneflower blossoms or stand tall to survey his domain. After three months of hibernation in his burrow, he comes out about now for his one semi-social season of the year. In a practice unique to groundhogs, the male emerges early to check his territory for the burrows of potential mates. He visits each female in turn for an overnight of cuddles and bonding, then hibernates another month before reappearing to mate with them all for real. His only role in raising the pups is to guard his territory against intruders. Where last week’s fluffball fit into this cycle is a mystery to me. Even February, my most difficult month, offers unexpected delights for the taking. My challenge is to notice more of them, without needing whistles and squeals to force them on my attention. Sources: National Wildlife Federation and Wildlife Animal Control. Image: Groundhog male, photo by Susan Sam, Michigan. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed