|

Last week temperatures rose to the nineties. Wildfire smoke from northern Quebec made outdoor air unsafe to breathe. My car was in the shop. Our phones were on the fritz. It would be a good week to stay in and clean. Not that I wanted to. Housework wasn’t mandatory, but it beat composing a sensitive email that would be difficult to write. I cleared out a filing cabinet of obsolete papers and made a start on sweeping the garage.

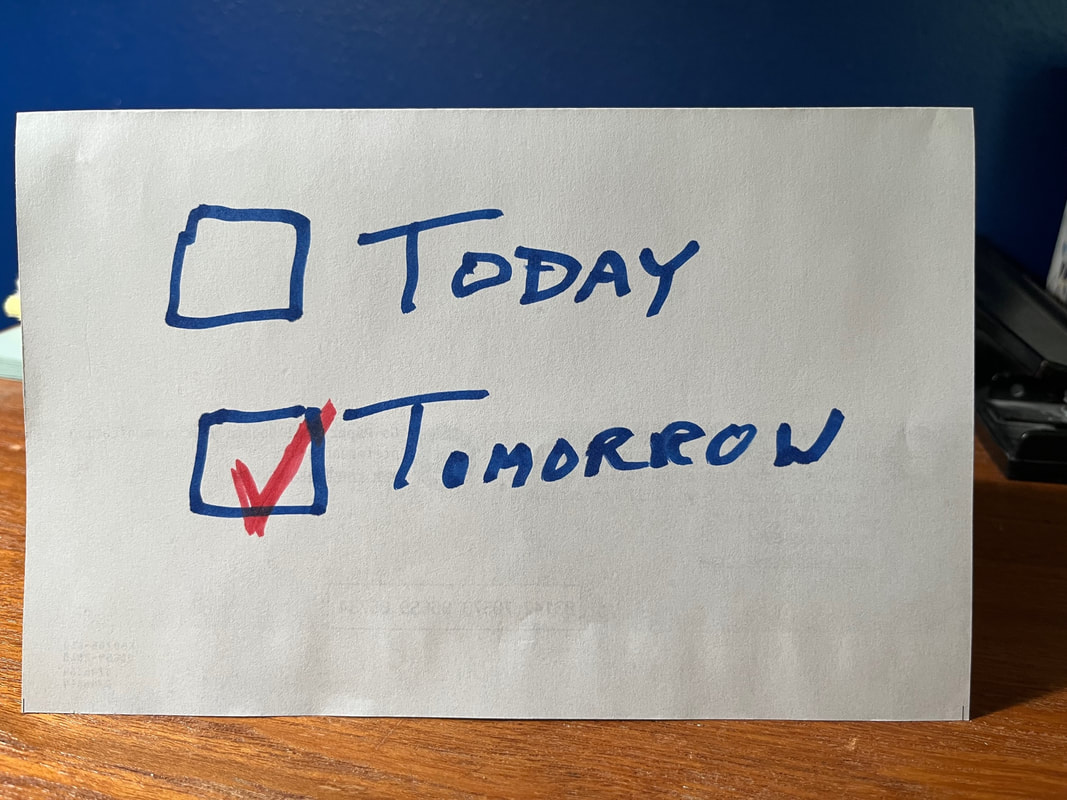

I’m puzzled when people list procrastination among their character defects. So long as a paper or project is finished by its due date, who cares whether it was completed at the last minute or well in advance? True, some obligations feel increasingly heavy the longer I delay. On the other hand, a few grow clearer or melt away of their own accord. Too bad I can’t tell in advance which is which. Perhaps the best thing about putting off the dreaded email was that it motivated me to other useful tasks for the purpose of avoidance. I wrote a few years ago about Stanford philosopher John Perry’s procrastination strategy. The top-priority activity will get done when it must, and meanwhile several lower-priority jobs get done that would never have happened otherwise.

8 Comments

Historical novels vary in how they weave fact and fiction. Some, such as Ellis Peters’s medieval Cadfael mysteries, place ordinary people in normal times very different from our own. Some suggest ways cataclysmic events like revolutions turn fictional lives upside down, as in Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities and Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. Others create narratives to fill gaps in the historical record. In The Secret History of Twin Peaks: A Novel, Mark Frost weaves conspiracy theories about the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-06 and Lewis’s death into backstory for the TV series he co-created with David Lynch.

A true historical puzzle led me to write fiction for the first time since childhood. Curious about the history of the Roma (pejorative Gypsies in English, Zigeuner in German), I learned that linguists traced their migration from India through Armenia to southeastern Europe by the 1300s. There Roma bands traveled around Hungary and the Balkans as wandering merchants and blacksmiths. Some in Romania were enslaved. Suddenly, with no clear cause, large groups of Roma appeared northern Germany in autumn 1417. City chronicles in Hildesheim, Luneburg, Hamburg, and along the Baltic reported dark-skinned, ragged strangers at the gates. The next year the strangers arrived in Frankfurt, Colmar, and Zurich. Soon they were in Italy and Spain. Claiming to be pilgrims from Egypt and carrying letters of introduction from the king of Bohemia, they accepted alms until townspeople drove them out. What triggered this mysterious migration? My factual draft got so filled with “perhaps,” “conceivably," and “one might hypothesize” that it was cleaner to drop the disclaimers and invent what might have happened. Fiction lets the story continue after the evidence runs out. Image: Evgraf Sorokin, Spanish Gypsies, 1853. As a sociologist’s daughter, I grew up aware that cultural and family background influenced my choices. Later, pondering determinism and free will, I observed how people who knew me well could predict those choices more accurately than strangers. Still, highly predictable people seemed stuck in a rut. Boring. Not me, surely.

Spellcheck made me suspicious at first when it pretended to know my intention. Now I find it useful, though no substitute for proofreading. (No, I don’t scoop up “humus” with my pita.) I’ve partly adjusted to text messaging that predicts the end of a word just started. But when my email program began to offer up whole phrases to add to an outgoing draft, it startled me how often it was right. Was I that predictable? Even to a total stranger? Apparently so. Setting aside the blow to the ego, it’s probably just as well. Imagine if every decision or action had to emerge from fresh consideration. Operating largely on predictable habit frees up mental energy for emergencies, creativity, and new learning. What’s worth fresh attention is partly a matter of choice. Image: Stuck in a rut, April 14, 2019. Covid isn’t over; it’s just past the emergency stage that overwhelmed health systems. Is life getting back to normal, or are some things forever changed? Is your life the same as it was four years ago?

We’re sitting on the riverbank watching the waters subside after a flood, wondering if the deluge left any lasting impact. That’s one perspective. Another is that we’re leaves and twigs floating downstream, flood or no flood. There is no going back. I can’t recall any four-year period in which the end was the same as the beginning. I can’t return now to 2019, whether I want to or not. The pandemic is only one cause among many. How about you? |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed