|

I’ve long asked why gratitude for blessings of home and family requires the presence of Pilgrims. Thanksgiving was an established regional holiday long before it acquired the Pilgrim myth, as I wrote last week. Even after 1863, when Lincoln named the last Thursday in November a day of national Thanksgiving, the story gained little traction. Ongoing wars on the Western Plains and the memory of the Trail of Tears made it hard to romanticize Indian-Pilgrim relations.

Only as immigration became a national issue in the 1890s did the Pilgrims take center stage. The families who came on the Mayflower could be cast as model immigrants: pious, industrious, and Protestant. New arrivals might learn American values from their example. Greeting cards, textbooks, school plays, and political speeches put the Pilgrims at the heart of the holiday. “How the Pilgrims would have enjoyed Budweiser,” boasted a newspaper ad in 1908; “how they would have quaffed it with heartfelt praise and gladness of heart.” Like a Rorschach inkblot, the Pilgrim myth could illustrate any cause. Theodore Roosevelt, a Progressive, said the Pilgrims were always willing to regulate conduct when necessary for the public good. Life Magazine during World War II described them as a strong-minded people who waged hard wars and knew victory comes from God. According to an anti-Communist ad in the 1950s, the Pilgrims rejected government dictation because they knew they’d have enough if every man worked for himself. * If some today frame the “first Thanksgiving” as a model of intercultural friendship, others deplore the offense to indigenous people in glossing over centuries of genocide. Why can’t we banish the Pilgrims from a holiday that wasn’t about them in the first place? Because we’d lose the opportunity to correct the tale with a more troubling history of settler-Indian relations? I’m afraid we’re stuck with the Pilgrims at Thanksgiving because their story can serve to support any assertion, even the assertion that their story isn’t true. *Robert Tracy McKenzie details these and other examples in “The First Thanksgiving in American Memory,” part 3 and part 4.

2 Comments

The Arab furniture maker in downtown Asmara wrinkled his forehead. Why did we need the table by late November? My description of hungry Pilgrims only puzzled him. Finally I blurted, “It’s the American harvest meal.” He nodded with a smile. Now he understood.

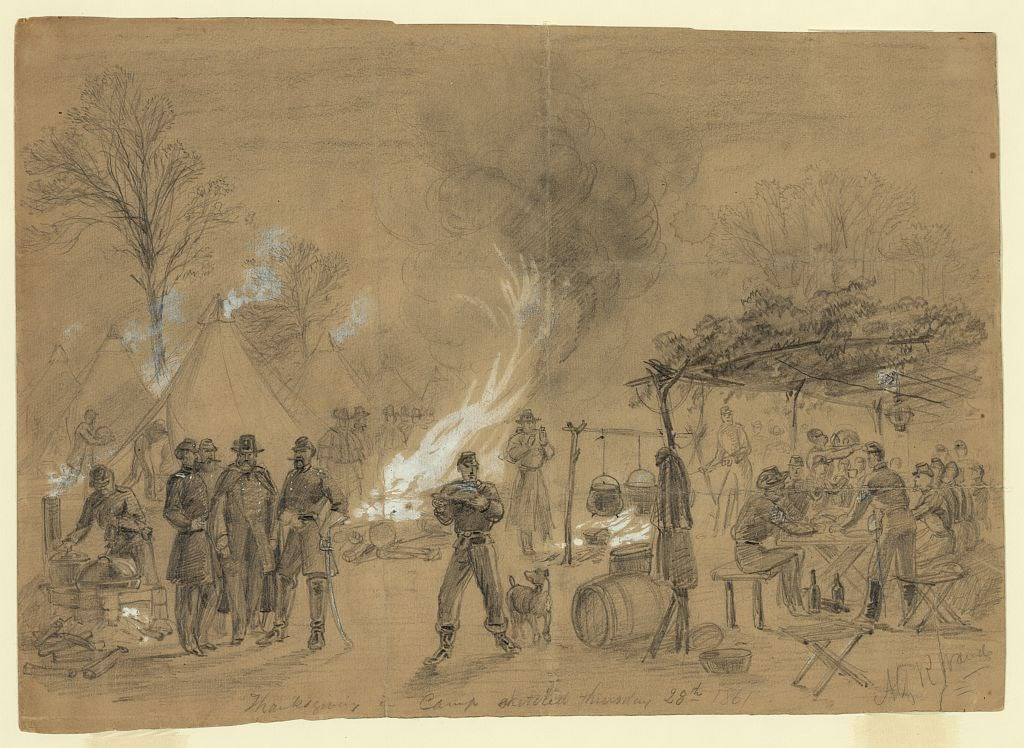

That was my first inkling Thanksgiving has nothing to do with the Pilgrims. Harvest feasts take place around the world. In addition, ceremonies of thanks for surviving a sea voyage, battle, or pestilence have a long history. After building Fort Caroline in Florida in 1564, French Huguenots sang a thanksgiving psalm and shared a meal. The next year, Spaniards landing at St. Augustine held a mass of thanks for safe arrival. Two weeks later they attacked Fort Caroline and slaughtered the Huguenots. Early Pilgrims and Puritans in Massachusetts brought from England a practice of prayerful thanks for specific blessings, with either a fast or a feast. Although they disdained regular holidays like Christmas, their New England descendants came to enjoy yearly Thanksgivings unrelated to any historical event. Lydia Maria Child’s poem “Over the river and through the wood” first appeared in 1844 as “The New-England Boy’s Song about Thanksgiving Day.” A 114-word sentence by Edward Winslow, which mentions neither thanks nor turkeys, is the only firsthand account of the harvest celebration at Plymouth in 1621. Winslow’s letter was virtually unknown in the U.S. until Alexander Young, a Unitarian minister in Boston devoted to local history, printed it in his Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers (1841). In a footnote, Young called the Pilgrim festivities “the first Thanksgiving.” He added, “They no doubt feasted on the wild turkey, as well as venison.” Among Young’s readers was Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book and author of the children’s poem “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” She published recipes for turkey and pumpkin pie. For years she lobbied to make Thanksgiving a fixed national holiday. President Lincoln made her dream a reality by proclamation in 1863. Neither Hale’s letter to Lincoln nor his proclamation made any reference to Pilgrims. How did a holiday unrelated to the Pilgrims get so tangled up in myth? More on that in next week’s post. Stay tuned! Image: Alfred R. Waud, Civil War Thanksgiving scene, 1861. Library of Congress. The 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones’s account of U.S. history centered on the effects of slavery, has caught the public imagination. Some call it truth at last. Others call it anti-American and introduce bills to forbid its use in schools. For lawmakers to decide historical fact makes as much sense as for churchmen to inform Galileo the sun goes around the earth.

History, like science, pursues knowledge by an established process of uncovering, evaluating, and analyzing evidence. Interpretation goes beyond raw facts. Viewing the past through an unaccustomed lens broadens our understanding. New questions, newfound evidence, and fresh perspectives make it a never-ending process. Whether a primary goal of the American Revolution was to preserve slavery, as Hannah-Jones asserts, is a question of fact, currently contested. Might a teacher use it to introduce historical method, from key documents to a final open-ended debate? PRO: A British jurist ruled in 1772 that a slave brought to England could not be held against his will, making colonial slaveholders fear abolition. CON: The 1772 ruling applied only to Britain; slavery remained entrenched in British-owned Jamaica and Trinidad. PRO: Governor Dunmore of Virginia in late 1775 promised freedom to any slave who fought to put down the rebellion. Many did. CON: Some colonial regiments also promised freedom to all who joined their cause. Dunmore’s promise, designed to harm rebel plantation-owners, did not extend to slaves held by Loyalists. Image: Elleanor Eldridge, Continental Army foot soldiers. An estimated 20,000 African Americans joined the British army; about 9,000, including Eldridge’s father, joined the revolutionaries. I wish Jennifer would come back to work.

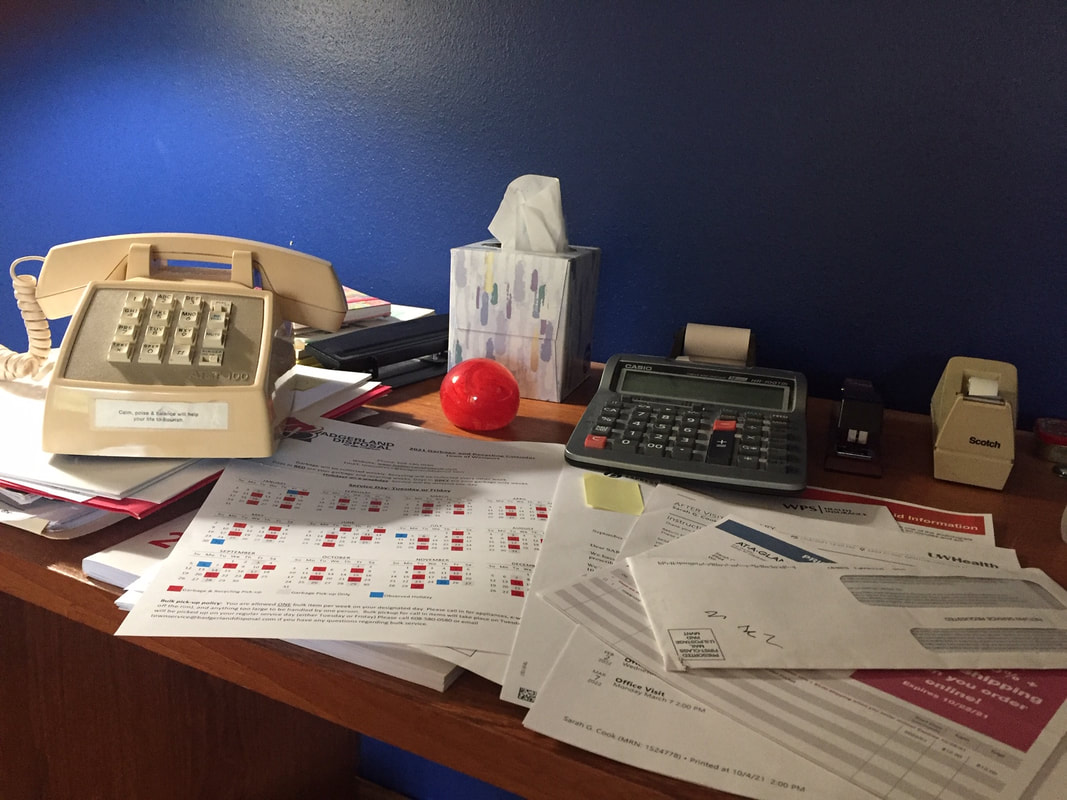

Children can have imaginary friends. Why can’t grownups? Not a friend in my case (I’m blessed with real ones), but the assistant I crave when personal business gets messy: billing errors to correct, records out of whack, phone calls on endless hold, websites that malfunction. If it starts to overwhelm, I sometimes conjure up Jennifer to give me a break. My alter ego slogs through the pile with mechanical detachment. She doesn’t relish the tasks but hey, it’s a job. When Jennifer is done, I come back ready to face the world again. Much we do now with push buttons and keyboards once involved interacting with humans, from the switchboard operator to the kid who pumped my gas. I don’t mean to romanticize the old way, which rested on low-wage labor. For routine, standardized transactions, the shift has brought us speed, efficiency, economies of scale, and nowadays the safety of social distancing. When matters get more complicated and live help is hard to find, I’d prefer a personal assistant take over. A couple of Novembers ago I wrote how things kept breaking. Does more go wrong as the days get darker, or does darkness make frustrations feel more pervasive? This year even Jennifer doesn’t want to come back to work. Imaginary characters, like the rest of us, may have a will of their own. The first very black faces I remember seeing were on the street corners of Morgantown, West Virginia, when I was very young. One day they disappeared. My mother explained the men were still present, going home from work, but they looked and dressed like everyone else after showers were installed at the coal mines.

I wouldn’t dress as an old-time coal miner for Halloween. Even a blackened face that isn’t blackface carries too much baggage. Nor would I play on other people’s suffering as a refugee, terrorist, prisoner, or Nazi; or an ethnic or marginalized group not my own; or what I know someone else to hold as sacred. Most Halloween costumes of my childhood were homemade and represented not individuals but generics: witch, pirate, cowboy, Indian, princess, Gypsy, lion, ghost. In later years I learned that “Indian” wasn’t so cool—they are real people, still among us—and even later that the same held for “Gypsies,” or Roma. We rarely dressed as hayseed hillbillies in my Appalachian childhood, and that caricature still irks me. Writers and readers play at being someone else all the time. Our scope may be wider than Halloween costumes, but the ground rules still apply. Avoid stereotypes, show respect for other people’s trauma, and take great care in portraying a culture not one’s own. Within these boundaries, reading about people of many sorts and backgrounds can not only show but even increase true empathy. Image: Children in Halloween costumes at High Point, Seattle, 1943, Seattle Post-Intelligencer staff photographer |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed