|

Apart from safety features, my car has few confusing bells and whistles. I chose it hoping still to drive it when I’m eighty. Slower reflexes and a steeper learning curve seem possible. As for traits more basic to who I am—personality and values, likes and dislikes—I don’t foresee much change.

The rapid changes of childhood slow as we grow toward midlife and beyond. At every stage, though, change continues more than we expect. Psychologist Dan Gilbert and others asked thousands of adults how much they’d changed in the past decade or expected to in their next decade. In every age group, reported change far exceeded expectations; 40-year-olds said they’d changed a lot since 30, while 30-year-olds didn’t expect to be very different at 40. Gilbert calls it “the end of history illusion,” the notion that numerous past transitions have brought us now (regardless of age) to the finished selves we were meant to be. It makes sense. Reporting the narrative of a remembered past is easier than inventing an unseen future. But underestimating future change can entice us to overpay for a years-from-now trip we won't still enjoy. It can drag us down with a sense of emptiness or failure we envision as permanent. What about long-term commitments like choosing a career or life partner, or bearing a child? They, too, may change more than we expected. With luck, the changes could prove richer and more rewarding than we ever imagined. Image: Janus, Roman god of transition, faces both past and future. Roman coin in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

2 Comments

Brightening deep December with raucous levity, Saturnalia was the merriest festival of the ancient Roman calendar. Inhibitions faded. Masters played at being servants, servants at being masters. The social order turned upside down. Chaos and mischief reigned.

Saturnalia is also my latest read in Lindsey Davis’s series about private investigator Marcus Didius Falco in imperial Rome. Celebrations of chaos have emerged again and again. Social role-reversal was central to the medieval Feast of Fools. Massachusetts Puritans banned Christmas in part for its drunkenness and debauchery. Chaos is scary, especially when fueled by anger or hate. Even chaos that starts in fun can easily flare out of control. Chaos and order; order and chaos. We see so much of both lately: riots and insurrection on one hand, hyper-monitoring on the other, all of it in such earnest. Order can never win totally. Some chaos will always break through. Rather than choose either extreme or seek a bland middle way, I’d rather lighten up and enjoy the dance. Savor Saturnalian chaos and order by turns, within basic boundaries of safety and respect. “You have such a wonderful collection of oldies!” the babysitter gushed, flipping through our 33 rmp Beatles, Doors, and Cream. Oldies? To us, they were just records.

“Vietnam? We studied about that in history class,” a young man told me later. To me it wasn’t coursework, but a major force shaping my life. None of my history classes ran past World War II, well before my earliest memories. Not until my freelance years editing K-12 social studies materials did I begin to see historical accounts of events I recalled. Some, like the Cuban missile crisis, I barely noticed when they happened. Martin Luther King’s assassination and President Nixon’s resignation held my full attention from a distance. A few, like the shootings at Kent State in 1970, hit closer to home as I visited a sister campus nearby. The older I get, the more current events conjure up times remembered. Nothing is new under the sun; everything is new because of context and hindsight. Histories depict the forest; we live from day to day in the trees. Writing memoir never drew me, but history always did. The line between the two grows ever thinner as I age. Image: Kent State University, May 4, 1970. I was at Oberlin College, babe in arms, to find student housing for my soldier husband’s return to finish his degree. All Oberlin (including the housing office) closed down on hearing the news from Kent. The evening of Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, my roommate’s boyfriend was to sing in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Yeomen of the Guard. His solo had the line, “With an ounce or two of lead, I dispatched him through the head!” When we learned midday that President Kennedy had been shot, our friend panicked. “I can’t sing that tonight! I know the show must go on, but I just can’t! I can’t!”

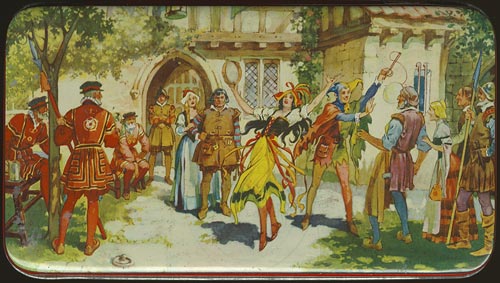

In retrospect, it’s obvious the show would be canceled, like everything else except meals. In the first shock of a personal or national emergency, though, I get disoriented. Nothing is obvious but reflex: save the cat, dial 911, fight/flee/freeze to escape the tiger. Figuring things out, redefining priorities, or discerning which shows must go on takes longer. Emotions are a blunt tool for rapid response, adapted to keep us alive in the moment. Reason is slower and more finely honed to let us analyze and plan. Survival requires both. To those who asked since last week’s post, I’m improving, thanks. Perhaps now just sick as a puppy. A couple of disorienting mini-emergencies along the way have settled into practical cancellations and reschedulings. Emotion and reason are each doing their part. Life is good. Image: Tin box with scene from The Yeomen of the Guard, 1888. Wikimedia Commons. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed