|

Is it my job to make sure I don’t infect you? Or is it your responsibility to avoid getting infected? Conflict between the two views is firmly rooted in American tradition, especially the settling of the West. For all the differences between coronavirus transmission and cattle trampling a neighbor’s crop, the issue is much the same.

Who is liable when my cows get into your corn? American fence law varies by state. Many require me to fence in my livestock to keep them off your property. Others with a high ratio of land to people, such as Wyoming and Texas, let cattle graze freely over vast areas. If you don’t want them on your fields or lawn, you need to fence them out. “Personal responsibility” holds more than one meaning. In the fence-out culture of the open range, it is about self-reliance. Whether and how to protect your property, your family, and your health is up to you. In the fence-in culture of market-gardening, cities, and suburbs, it is about interdependence. Urbanites rub shoulders daily. We rely on shared water and sewage disposal. We each have a part to play in protecting the health and safety of all. Neither fence-in nor fence-out law is a moral absolute. Tracing cultural values to context won’t resolve differences over pet leash ordinances, guns, or face masks. But it might ease our indignation enough for conversation to begin.

5 Comments

The men at the corner of High Street and Pleasant were black from head to toe. My mother said they were miners who had just left work. One day they disappeared. Mother said they were still there; they just looked like everyone else. With newly installed showers at the mines, the men could clean and change clothes before heading for home.

On the wooded slopes across the river from my childhood home, tipples carried coal to railroad cars for transport. The men who dug it earned union wages for dangerous work deep underground. They got quality health care at United Mine Workers hospitals and clinics. In 1949, mining in West Virginia extracted 122,913,540 tons of coal and employed 121,121 people. During my 1950s childhood, automation in the deep mines cut into jobs. Strip mining heightened unemployment in the 1960s and 1970s. Slicing tops off mountains for easy access is highly mechanized, and explosives are cheaper than people. Employment and union membership plummeted. By 2004, the industry extracted 153,631,633 tons statewide with only 16,037 workers. Mountaintop removal not only slashed jobs by 90 percent but also destroyed forests and animal habitat. Erosion, flooding, and contaminated drinking water followed. Given adequate resources, the state that led the nation in Covid vaccinations can model rural recovery. Isolated communities need access to broadband, local health services, and jobs that can’t be outsourced. Healing may begin, in part, with restoring the wooded mountaintops of my childhood memories. “Beware the Ides of March,” a soothsayer warned Julius Caesar in Shakespeare’s portrayal of the dictator’s murder. According to ancient biographer Plutarch:

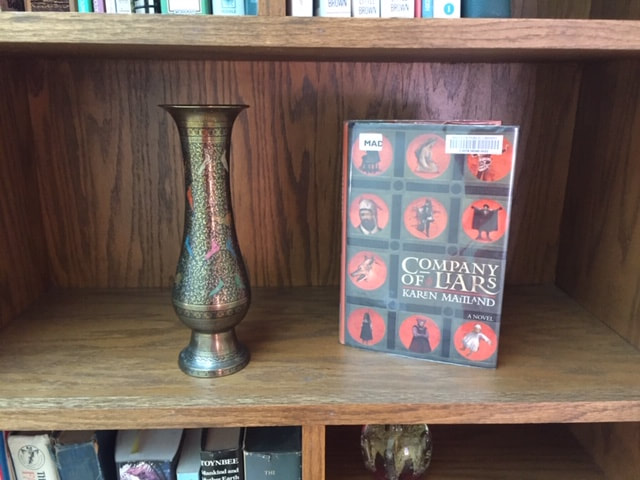

A certain seer warned Caesar to be on his guard against a great peril on the day of the month of March which the Romans call the Ides; and when the day had come and Caesar was on his way to the senate-house, he greeted the seer with a jest and said: “Well, the Ides of March are come,” and the seer said to him softly: “Ay, they are come, but they are not gone.” In the Roman calendar, Idus referred to a specific day mid-month: the 15th of March, May, July, or October, and otherwise the 13th. For reasons unknown, perhaps even to the Romans, Idus was always plural. Shakespeare made Ides plural in English, too. It’s the same word if treated as singular; no related “ide” exists. In practice the grammar is messy. What rule explains why “The Ides are looming” sounds fine, but “The Ides of March were Saint Nicholas’s birthday” would work better with the singular was? The fated date turned out badly for the dictator who overthrew the Roman Republic. The Ides of March brought other misfortunes over the centuries, including WHO’s global health alert for SARS in 2003. This morning, after months of troubles, March 15 has arrived with no new disaster I’m aware of. So far. Karen Maitland’s medieval Company of Liars (Delacorte Press, 2008), which I read last month, is a welcome addition to my short list of historical novels on epidemics. I found the book haunting, thought-provoking, and hard to put down.

In the summer of 1348, when the plague first arrives in England from abroad, strangers thrown together by happenstance hit the road to escape infection. Like us in early 2020, they can only guess how far or how fast the contagion might spread. They meet locked doors and gates where they might have found welcome in healthier times. As they flee, they entertain each other with misleading stories of their lives. Which will catch up with them first, the pestilence or their lies? The plague journey intrigues me because I think of epidemics as fixing people in place. The fictional storytellers in Boccaccio’s Decameron (1349-1353) hunker down in a villa outside Florence to avoid the plague. Residents of the infected village in Geraldine Brooks’s Year of Wonders, set in 1666, agree to stay put so as not to infect others. Some of us during Covid are in quarantine or under lockdown orders. Do shutdowns have a contrary effect of setting some people in motion? If so, I wonder who today’s pandemic travelers would be. Families roaming and sleeping in their vans? Students removed from closed dorms? Overflow from homeless shelters limited by social distancing? Is it possible to wall some in for safety without walling others out? What delight to turn the calendar page to March! By some measures this is the beginning of spring. I haven’t seen a robin yet, but neighbors have.

When we went into lockdown almost a year ago, someone asked what I missed most. “Making plans,” I said. Normally by March I would be looking forward to family visits from afar, a long weekend in Door County, a day at the Bristol Renaissance Faire. With no idea how long the pandemic would tie us down—maybe two or three months, we feared—planning was impossible. A nebulous “when this is over” was no substitute for a scheduled treat. Anticipated joy is the pleasure we expect from an experience in the future. Anticipatory joy is the happiness we get right now from planning a future pleasure. Some people get through the winter by pouring over seed catalogues. I used to map out summer vacations, more than I would ever take. Active engagement in planning a good time can bring nearly as much happiness as when the plans materialize, and sometimes more. It reduces stress and elevates mood. The snow will melt, evenings lengthen, daffodils bloom, vaccinations expand, infections continue to fall. It’s not too soon to plan forest hikes and outdoor gatherings. There is hope. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed