|

If asked the cause of the Civil War in one word, I’d have to name slavery. South Carolina declared independence after Lincoln’s election as president, “whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.” According to its Declaration of Secession, the 1860 election culminated 25 years of “increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery.” Although the immediate trigger to cannon fire a few months later involved a state’s right to secede, that issue arose from the South’s commitment to slavery.

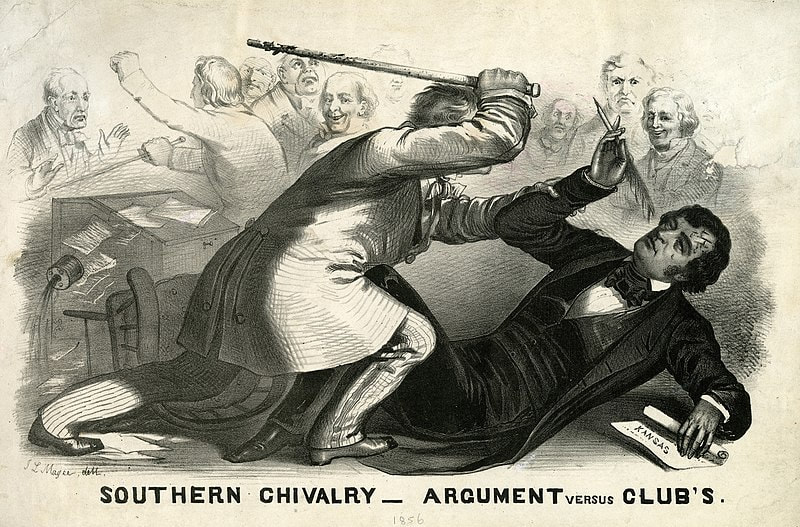

One-word answers are for promoting an agenda, not for exploring history. Cause-and-effect narratives are rarely so simple. Causes of resentment between the agricultural South and the increasingly industrial North were as old as the Republic. Then as now, states that feared or resented control by national majorities have claimed states’ rights on policies from tariffs and slavery to marijuana, abortion, and guns. Article VI of the U.S. Constitution makes federal law supreme over any conflicting state law. The Tenth Amendment reserves to the states any powers not given the federal government. Between the two, “states’ rights” can mean almost anything. Curiously, while we tend to associate states’ rights with the South, it was northern states that claimed a right to nullify the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The act required northerners to return people fleeing slavery and punished anyone who helped them. South Carolina’s Declaration of Secession names thirteen northern states that “have enacted laws which either nullify the Acts of Congress or render useless any attempt to execute them. In many of these States the fugitive is discharged from service or labor claimed, and in none of them has the State Government complied with the stipulation made in the Constitution.” In other words, when it came to preserving slavery, northern states had no rights in the face of conflicting federal law. No, friends, states’ rights weren’t even a secondary cause of the Civil War. They were only an excuse when they happened to favor slavery. Image: John Magee, “Southern Chivalry – Argument versus Clubs,” lithograph, 1856. Preston Brooks (SC) beats Charles Sumner (MA) over slavery in the U.S. Senate chamber.

0 Comments

Viking, Scottish, and Irish culture revolved around honor, shame, and violence in response to insult. Honor culture came to America with the Scots-Irish who settled in the Appalachian South. Status rests more on birth and family than individual achievement or guilt. People are expected to know their place. Disrespect is the greatest offense. To appear a loser is worse than to know oneself a sinner.

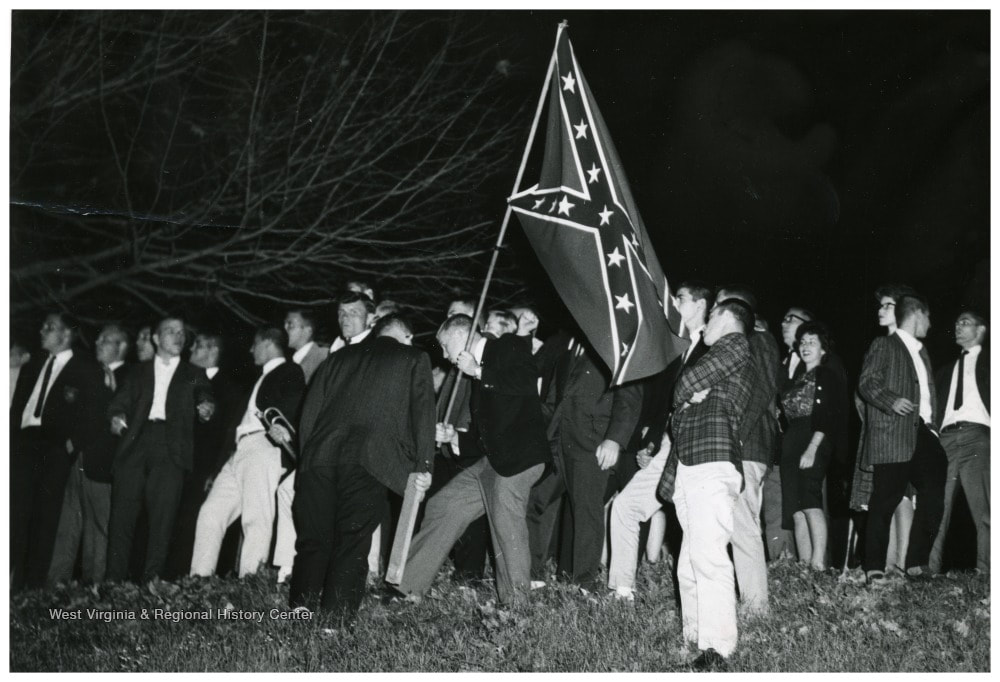

This helps me make sense of the history I learned in West Virginia public schools long ago. We took pride in the Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, born in Clarksburg just up the river, and the legendary freedom of mountaineers. We deplored tobacco plantation field slavery but condoned household slavery as benign. We interpreted the Civil War as a conflict over states’ rights, not slavery. Nobody likes to lose, but it is worse when losing carries dishonor and shame. From a Northern, guilt-and-atonement viewpoint, the Confederates fought to preserve slavery and lost. From a Southern viewpoint, honor was at stake. Flags and monuments are not about remembering history, but rather about honor and respect. “You lost, get over it” means nothing except as a further insult. Image: Henry Mosler, The Lost Cause, 1869. Morris Museum of Art, Augusta, Georgia. Growing up just south of the Mason-Dixon Line, I saw a fraternity at West Virginia University fly the Confederate banner. That flag appears less often now, except in white supremacist contexts. In 2019 a third of American adults who were asked whether it represents heritage or racism (or other, or don’t now) chose heritage. The percentage was higher among respondents who were older, white, or rural. How well does the “heritage” answer hold up?

The Confederate States of America based their flag of 1861 on that of the Union. To avoid confusion in the heat of battle, southern military units adopted their own distinctive flags. Most popular was the battle flag of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. After the war, it was used on soldiers’ graves and at veterans’ events. The Kappa Alpha college fraternity in Virginia displayed Lee’s ANV banner regularly. By the early 1900s it became a popular symbol of the Confederacy and the South at intercollegiate football games. The Ku Klux Klan began to raise the ANV battle flag in the 1930s and 1940s, especially after World War II. Dixiecrats, a segregationist splinter party of former Democrats, featured it in the presidential election of 1948. It came into its own in reaction to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ‘60s. Many white Americans of my generation were taught the Confederate flag represents heritage. The South has a long, rich, distinct cultural heritage. Its contributions to American literature, music, cuisine, and religion cross racial lines. To represent it with a relic from a few years of devastating warfare dishonors the many aspects of that heritage of which the South can be justly proud. Image: Kappa Alpha Fraternity Raising the Confederate Flag, West Virginia University, 1967. When the grandfathers dozed in their chairs, I told my child that’s what grandfathers do. After father nodded off too, I explained he was practicing up to be a grandfather.

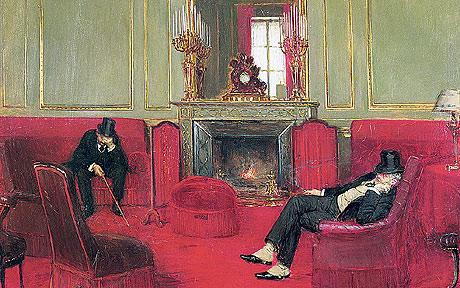

I don’t know who first tied virtue to sleep cycles. “Early to bed, early to rise” long predates Benjamin Franklin. Consider, for example, As the olde englysshe prouerbe sayth in this wyse. Who soo woll ryse erly shall be holy helthy & zely.* - The Book of St. Albans, 1486 Maybe it’s because teens, stereotyped as reckless and rebellious, prefer to sleep in. Of the many factors that can reset a body clock, the most nearly universal is age. Hormonal changes, not laziness, keep teens awake well into the night. Early school start times leave them with too little sleep, increasing their likelihood of risky behaviors, depression, and poor academic performance. The circadian rhythms of older adults get weaker and shift to a shorter-than-24-hour cycle. Many elders wake early, doze or nap by day, and fade soon after supper. On cognitive tests, they perform as well as younger folk in the morning but much worse in late afternoon. As with teens, sleep shortage and personal schedules at odds with their body clocks can play havoc with health, mental ability, and mood. To the extent circumstances allow, it’s wisest and healthiest to shape your life to fit your circadian rhythm. *Zely meant “fortunate.” Image: Jean Beraud, two gentlemen at sleep while wearing top hats in ‘The Club,’ painted 1911. In The Telegraph, “How many can point to a true gentleman?” Oct. 17, 2010. Are you a morning person or a night owl? Did you bounce out of bed hours before dawn to greet the new year, or did you ring it in at midnight wide awake? The days have been growing longer for eleven days by now. Do you notice the difference? Me neither.

Like other animals and plants, our bodies respond to changes in the light. Human internal clocks vary by nature and nurture. Based mostly on input from eyes, a master clock in the brain signals cells throughout the body to speed up or slow down. This coordinates daily cycles of hormones, sleep, mood, body temperature, appetite, digestion, and more. If your clock runs a little faster than 24 hours, you’ll tend to wake up early. If it’s a little slower, you’ll get sleepy later. Neanderthal ancestry may play a part in making some people early risers, according to recent research. Neanderthals in Europe, where seasonal changes in daylight favored faster, more flexible circadian rhythms, interbred with Homo sapiens. Humans of European descent today have between 1 and 4 percent Neanderthal DNA. The higher your percentage, the more likely you carry genes for a faster body clock. Stay tuned next week for more on body clocks and why they matter. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed