|

Seven years ago, my sewing machine got lost in a move. Its replacement finally came out of the box this month. With seven years of mending to catch up on, it was time to relearn. Oh, yes, here’s the pressure foot. Oh, yes, here’s the bobbin case. Where I didn’t expect trouble was in threading the needle. I often thread needles to sew by hand, but the one in the machine refused to cooperate.

Guiding a thread through the narrow eye of a needle must be as old as sewing itself. Our word needle goes back via Old English to Proto-Germanic, and ultimately to Indo-European. Passing an elephant or camel through a needle’s eye is an ancient metaphor for doing the impossible. Later, threading the needle became an analogy for moving through tight human spaces in sports, children’s games, and yoga. Politicians and managers must sometimes thread the needle to navigate a careful, delicate course between groups with conflicting goals. Most days, at this stage of my life, I’m grateful the hardest needle I have to thread is the one on my sewing machine. Images: (left) Bonifatius Church portal relief in Dortmund, Germany, re words of Jesus; (right) Johann Vogel, engraving, 1649, cropped, re seemingly impossible Peace of Westphalia.

2 Comments

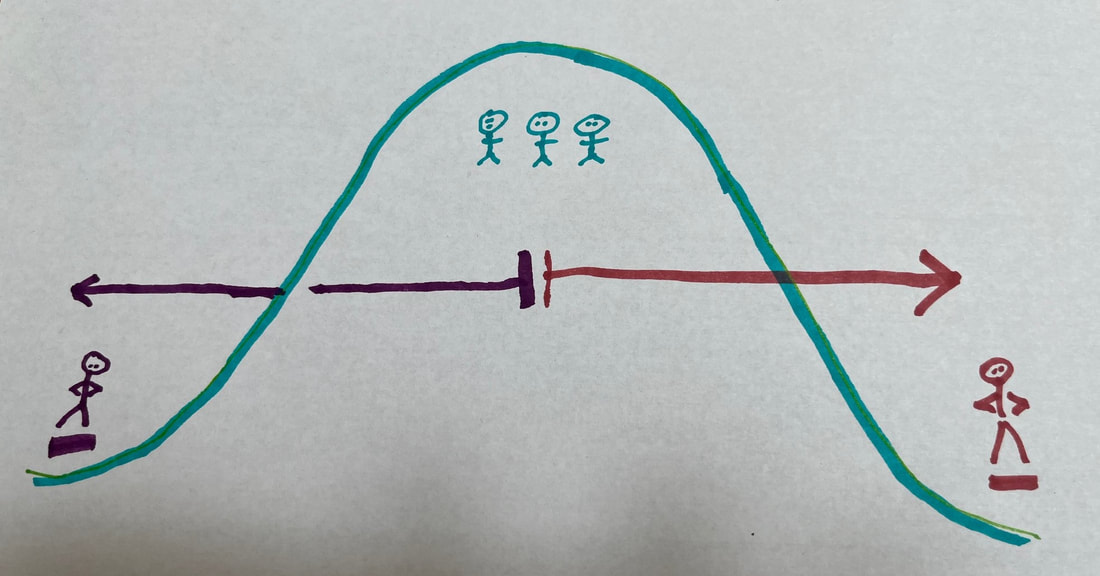

“I act like an extrovert, but I think I’m really an introvert,” a friend told me. Many of us have used Myers-Briggs or similar instruments to define our personality types. Duke University psychology and neuroscience professor Mark Leary says scientists prefer to talk about traits instead of types. People are infinitely varied. Most personality traits occur not in opposing pairs but along a bell-shaped curve. Some people are very sociable, others just want to be left alone, but the vast majority of us—perhaps including my friend—fall somewhere toward the middle.

Winter, summer; good, evil; dark, light; rowdy, orderly. Is it human nature to prefer dualism over nuance? For some, clear-cut categories feel better than the ambiguity of a continuum. They make for catchier headlines and greater charisma. I wonder if binary thinking not only reflects but increases polarization. Take politics: Ordinary folk seem more moderate on average than fit precisely into progressive or conservative boxes. Take masculine and feminine personality traits: Are they inherent or socially constructed? Surely some of each. Young men’s and women’s hormones tilt the former to apply physical strength and the latter to bond with their babies, but plotting each on a bell-shaped curve would reveal huge variety and overlap. It needn’t be either/or. When did you last walk from one room to another, only to forget why you’re there? I do it several times a day. Our brains, finite but efficient, use environmental clues to help choose what to remember. When the setting changes—a different room, for example—they tend to wipe the slate clean to make space for something new. Psychologists call it the doorway effect.

The problem is not so much how to retrieve a memory as how to record it in the first place. I try to follow at least a couple of these tips before I reach the doorway:

Now, why did I come in here to the computer? A former neighbor dismissed concerns about climate change, saying this warming trend is just another of the climate shifts that occur naturally from time to time. He was right about long-ago climate changes and wrong about the cause of this one. What intrigues me, though, is the assumption that if today’s climate change were of natural origin, it would give no cause for concern.

Thriving Bronze Age cultures of the Mediterranean world—Egypt, Canaan, Crete, Mycenaean Greece, and the Hittite Empire of Asia Minor—disintegrated rather suddenly in the century after about 1200 BCE. Analysis of fossilized pollen reveals a severe drought throughout the region. Famine led to upheaval, mass migrations, attacks by “sea peoples,” disruption of trade, abandonment of Greek and Hittite writing systems, destruction of palaces and cities, dispersal into small rural settlements, and the fall of Troy. Fast forward through the rise and fall of Rome and beyond. Vikings from Scandinavia raided and settled in Scotland, Ireland, northwestern France, and even southern Italy. They settled Iceland, previously uninhabited except for a few Irish monks, and southern Greenland, separate from the Inuit in the north. After about 1300, with the end of the “medieval warm period,” icebergs made trade with mainland Europe treacherous. Unable reliably to exchange trade walrus tusk for essentials like grain, Norse Greenlanders either left or died out. Iceland survived, but barely. History gives no reason to suppose climate change is benign to humans so long as humans didn’t cause it. In fact, human-caused climate change could potentially have one advantage. Unlike the natural disasters of past millennia, those caused by humans might potentially be resolved by humans, if we could summon the political will to do so. Image: Kerstiaen de Keuninck, (c. 1561-1635), Fire of Troy, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed