|

My weekly yoga class switched from studio to online early in the pandemic. Happily, the class remains small and personalized. Some make yoga a spiritual practice. Our instructor says we’re all building strength, endurance, flexibility, and balance.

Life often reminds me these qualities aren’t just physical. Now, for example. February has been so . . . February. Snowdrops are in bloom; snow is in the forecast. The season calls for strength to do what needs doing; endurance to keep at it; flexibility to change plans as weather and health require; and balance to welcome tiny harbingers of spring while hunkering down for a blizzard.

2 Comments

Zoom in or zoom out? How much background or context does a true narrative provide? It’s a question of craft and purpose. In Born in Blackness (2021), Howard French traces the transatlantic slave trade to Portugal’s quest for African gold. As I’ve written before, the story begins where the storyteller begins it. The same holds for the ending: Juneteenth? Jim Crow? This week?

Historians deal in evidence and interpretation. Truth or falsehood rests large on evidence; interpretation is better described as persuasive or weak. Evidence can be mixed. The late Professor Geoff Blodgett recalled serving as ship’s historian during a naval battle in the Korean War. Interviewing sailors the very next day, he found that every one of them recalled the battle differently. History is neither an art nor a science, Blodgett told us. It is a craft. In the mystery novels of my leisure reading, crime scene photographers document a scene at many scales and angles. In history, the more different angles we can see from, the closer we come to understanding what happened and why. Image: (left) Cropped by me, from (right) Monarch flying away from a Mexican sunflower. Wikimedia Commons (license). For years I learned Americans won their Revolution due to such advantages as knowing the terrain. Not until grad school did I hear about dissention in Britain as the war dragged on. “I am persuaded and I will affirm, that it is a most accursed, wicked, barbarous, cruel, unnatural, unjust, and most diabolical war,” William Pitt said in Parament in 1781. “The expense of it has been enormous . . . and yet what has the British nation received in return?” James Boswell wrote in his diary, “Opinion was that those who could understand were against the American war, as is almost every man now.”

Fast forward to America’s loss in Vietnam. I hear more about dissention within the U.S. than Vietnamese factors conducive to victory. Why the difference in emphasis? Hypocrisy? No; win or lose, it is natural that Americans look at wars primarily in terms of happenings in the U.S. As in photography, the picture necessarily varies with the angle from which one looks. Even attempts to cover multiple angles do so by jumping from one to another, like a series of still photos rather than one that’s all-inclusive. Other terms to describe narrative viewpoint include the lens through which writers look and the focus where they concentrate attention. Which is true history, the view from Britain or the United States, from the U.S. or Vietnam? Both, if they’re supported by evidence and don’t claim to have a monopoly on truth. Image: Regnier, Washington the Soldier, 1834. Library of Congress. Was the rise of the United States built on Enlightenment ideals or slavery? I welcome the current spate of interest in books, lectures, and classes about race-based slavery and its consequences. When friends say they’ve finally learned America’s true story, though, I’m skeptical.

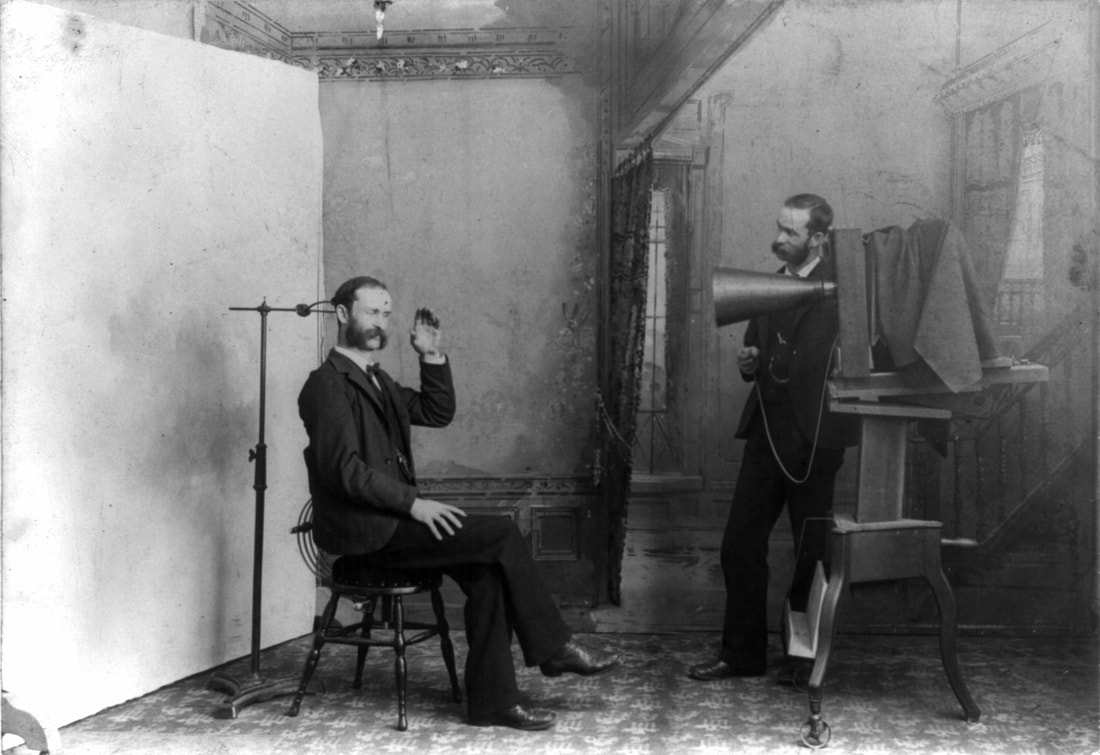

To understand why, imagine you’re an experienced photographer hoping to write a history about a topic of your choice. You know many accurate ways to photograph a single subject. The same holds for recounting the past. Some photos or narratives, of course, are false. Remember when the University of Wisconsin’s admissions office inserted a Black student’s head into the image of an all-white crowd to indicate diversity? In a story contrived to mislead, we call it lying. If you doctor your story for entertainment or artistic expression, it’s called historical fiction. Honest nonfiction is far from mechanical. Applying your photographic experience to writing a true history leaves you plenty of scope for creative choices. I’ll write about a few of those choices in the next couple of weeks. First of a three-part series. Next week: Angle, Lens, and Focus. Image: A.H. Wheeler, photographer, Berlin, Wisconsin, 1893. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed