|

I wrote my British history dissertation during the Vietnam War. While I pored over 300-year-old documents in libraries and archives, American men were drafted or fled to Canada. Chaos erupted on the streets. Richard Nixon was elected president. My research topic, how Puritan John Owen’s theology shaped his ties to Oliver Cromwell in England’s civil war, seemed far removed from current events; but my findings changed how I see the world.

The notion that “the end justifies the means” seemed straightforward. Wasn’t a worthy end the only reason to use any means in the first place? Hey, I was young. On 4”-by-6” note cards, I recorded how Owen defended beheading the King and throwing out one Parliament after another when their actions conflicted with God’s will. In Washington, President Nixon backed a burglary to help him win a second term. In musty archives, I wrote how 17th-century Puritans put England under military rule, and a fed-up nation finally welcomed a Royalist army to restore the monarchy. On the radio over a colleague’s dining room table in 1974, I heard Nixon resign office rather than stay to be impeached. My take-away from Owen’s biography was that process matters more than winning. It is best in the long run to admit the loss of a free and fair election, to abide by legislation we dislike, to uphold the Constitution even when we work to amend it. Yes, some life-and-death cases must yield to conscience, like the Underground Railroad or water in the desert for parched migrants. But to justify win-at-all-costs methods by framing policy debates as life vs. death, socialism vs. fascism, sets everyone up to lose in the long run.

0 Comments

Friends and neighbors used to rave about elegant Southern plantation houses they’d toured on vacation. Plantation weddings are still popular. But Whitney Plantation west of New Orleans won’t touch the wedding business. Opened to the public in 2014 as a museum about slavery, Whitney refuses to romanticize its past.*

Times are changing . . . gradually. Four years ago, I visited the historic San Diego de Alcala mission church in California. As I recall, a brochure described how and why Spaniards built a mission in that spot, how the priests lived, and what challenges beset them. The next year at Mission San José in San Antonio TX, a ranger explained how drought and disease drove native inhabitants of the region to live and work on the mission grounds. In time they and their descendants created a whole new culture, blending indigenous foods and customs with Spanish language and Catholic faith. The histories we hear depend in part on what questions we ask. If we only ask about the white people in charge of a plantation or mission, we turn to Gone With the Wind for images of suffering. I’m glad there’s a rising interest in asking, researching, and teaching about the forced labor that made plantations and missions possible.** Enslaved people’s sufferings are painful to imagine and, I hope, impossible to romanticize. * Image: Whitney Plantation slave cabins. For more on how diverse sites and programs portray slavery, read How the Word Is Passed by Clint Smith (2021). ** According to the National Park Service, “Tradition has it that the missionaries never forced anyone into a mission, but once there, they could not leave. Those who ran away were often tracked down and returned to the mission.” Crowds at the gym are starting to thin. Most people who make New Year’s resolutions quit in a matter of weeks. While I rarely set turn-of-year goals, I sometimes identify—and then forget—a focus for the coming year or a habit to leave behind. Can such short-lived annual practices serve any useful purpose?

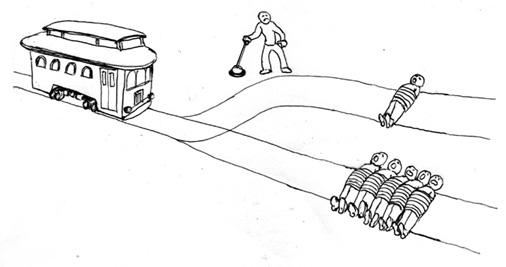

I believe so. Most of daily life, mine at least, is guided either by routine or by response to immediate events. That’s just as well; to decide each action minute by minute would be overwhelming. But once a year, whether at New Year’s or some other fixed date, I might do well to step back from the trees of every day for a longer view of the forest. How is it with my life? Which routines still serve me? What cries out for gratitude, or adjustment, or recommitment? Is it time to begin baby steps toward something new? It hardly matters whether that long view leads me to make and keep a resolution. Even if I forget the specifics, pausing to look at the forest may shape how I perceive the trees for many months to come. In war, it’s called collateral damage. In medicine, adverse side effects. Few of us would kill one innocent person to save another. Would you do it to save a hundred? A thousand? A million? Moral philosophers call this the trolley problem. If you saw a trolley hurtling toward five people tied to the track, and your only option was to switch it to another track with just one potential victim, would you pull the switch?

We seem hard-wired to accept greater harm from impersonal causes than from human deeds. To ignore preventable storm damage feels less wicked than inflicting comparable damage. Inaction, sins of omission, or leaving matters to nature or chance ranks higher in our moral instincts than committing active harm, however small. Some take it a step farther, calling nature inherently good. Human intervention feels suspect. Before vaccines, polio paralyzed about half a million children a year. Mass vaccination largely eliminated the disease in industrialized countries by 1988, but polio still paralyzed or killed some 350,000 a year in developing countries—a thousand children a day. Mass campaigns with a cheaper, easier-to-administer oral vaccine eradicated two types of naturally occurring polio and reduced the third type to only 6 cases in 2021 and about 30 this past year. But 2022 also saw between 500 and 600 children paralyzed by polio that could be traced to mutations in that same oral vaccine. A new, more genetically stable vaccine should resolve this problem. Meanwhile, which is worse: hundreds of children paralyzed because of indirect human action, or hundreds of thousands paralyzed naturally whom humans could have saved? It’s a real-life version of the trolley problem. Which alternative shocks you more? Which keeps your child safer? The turn of the year brings out platitudes. “Every ending is a new beginning.” “Out with the old, in with the new.” The date of the supposed fresh start is arbitrary, of course. Remember the relief when annus horribilis 2020 was finally hindsight? Then came January 6, 2021. The gods laughed, “And you thought the worst was over.”

Most changes evoke mixed feelings. Anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski suggested societies use rites of passage, at changes of personal status, to reinforce the more desirable elements in the mix. A wedding ceremony, for example, highlights joyful commitment and downplays loss of freedom. Though few New Year’s celebrations are true rites of passage, they offer a similar purpose. Parties, toasts, and "Auld Lang Syne" call us to remember the past but not to wallow in it. Acknowledge grief but don’t despair; the sun will rise again. And if the past year stank, raise a glass to “good riddance” instead of plotting endless cycles of revenge. Out with the old, in with the new. Image: Reporter and artist Marguerite Martyn, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Jan. 4, 1914. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed