|

Efficacy. Herd immunity. Mutations. Clinical trials. I've never seen more people pay more attention to vaccine science than with Covid. Less noticed is another important new vaccine, long after Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin developed the first polio vaccinations.

No vaccine is perfect. Poliovirus won’t paralyze you if you’ve had your Salk shots, but it can still pass from your gut to paralyze someone else—much as my Covid vaccination may still let me infect you. Sabin’s polio vaccine, taken by mouth, avoids this by destroying poliovirus in the gut. Where vaccination rates are low, though, harmless live virus from the vaccine can pass from person to person long enough to mutate and do harm—much as coronavirus mutates into new strains in the absence of herd immunity. Hence the excitement about nOPV2, the novel oral polio vaccine type 2 set for use in 2021. It offers the best of both worlds, targeted to virus in the gut and genetically modified to avoid mutation. It may help end polio once and for all. Image: Participants in an nOPV2 clinical trial lived four weeks in Poliopolis, a container village in Belgium. Photo credit: Ananda Bandyopadhyay, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

0 Comments

“Unprecedented!” We hear the word almost daily, alongside a steady stream of precedents. The 1918 flu. Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson. Protests in the 1960s. Polio vaccine development. Charlottesville’s Unite the Right. The disputed 2000 presidential election. And week after week, the Know-Nothings of the 1850s.

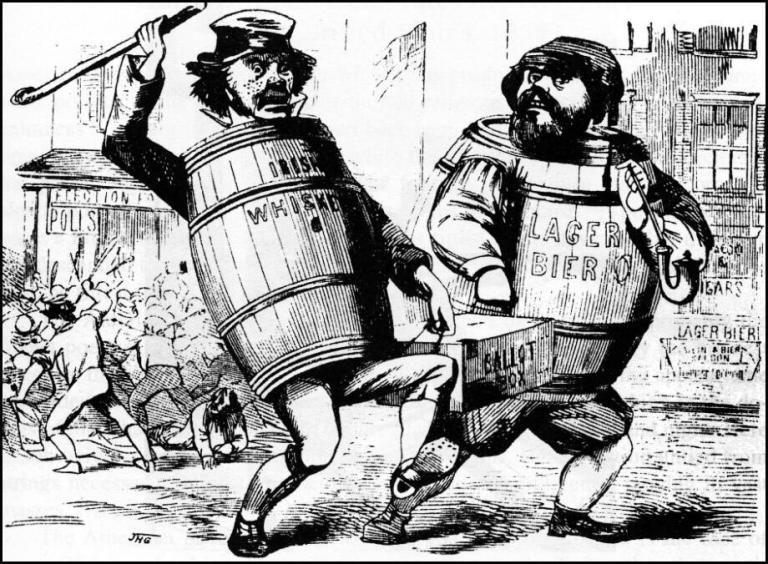

Conspiracy theories heightened the Know-Nothings’ zeal to protect the American way of life (native-born, English-speaking, Protestant) from Irish and German Catholic immigrants. Their nickname referred to members’ secrecy: “I know nothing.” They resented outsiders, elites, and expertise. To defeat a supposed plot to bring the U.S. under papal rule, they won local elections and used intimidation to keep Catholics from voting. Violence by Know-Nothings erupted in at least seven major cities between 1854 and 1858. In Louisville’s election day riots of 1855, attacks on immigrant Catholic neighborhoods by Protestant mobs left 22 dead. Dozens were injured. Fire destroyed homes and businesses. Of the five participants later indicted, none were convicted. From hyper-nationalism to conspiracy theories to deadly violence—what next? The Know-Nothings quickly passed into history with the rise of the new Republican Party. Within a few years of their demise, the nation was engulfed by civil war. I reckon historians looking back on this period will have to reckon with deep national divisions, a pandemic reckoned from its arrival here over a year ago, a presidency some reckon the nation’s most corrupt, and an attack on the U.S. Capitol. Historians will reckon the pros and cons of an impeachment by elected leaders who call for a reckoning.

Reckon comes from an Old English term of Germanic origin meaning to explain, relate, or arrange in order. By the 1300s it also meant to count or calculate, and a reckoning was a settling of accounts. Account (from Old French, c. 1300) meant a detailed statement of money owed or spent. “Having to report on the finances” soon broadened to “having to answer for one’s actions,” or being accountable. On account of this latter meaning, a historical account of recent events will have to take into account the debate on whether accountability is possible without a reckoning. I have been watching the PBS documentary “Reconstruction: America After the Civil War” by Henry Louis Gates. It shows a different picture from what I learned in West Virginia public schools long ago.

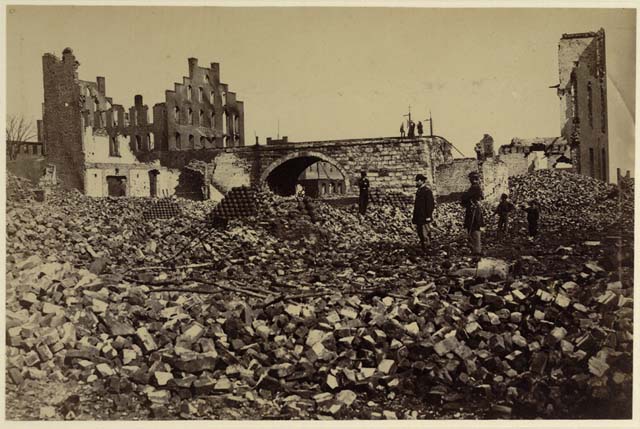

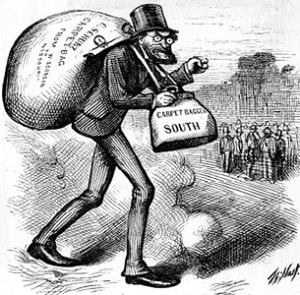

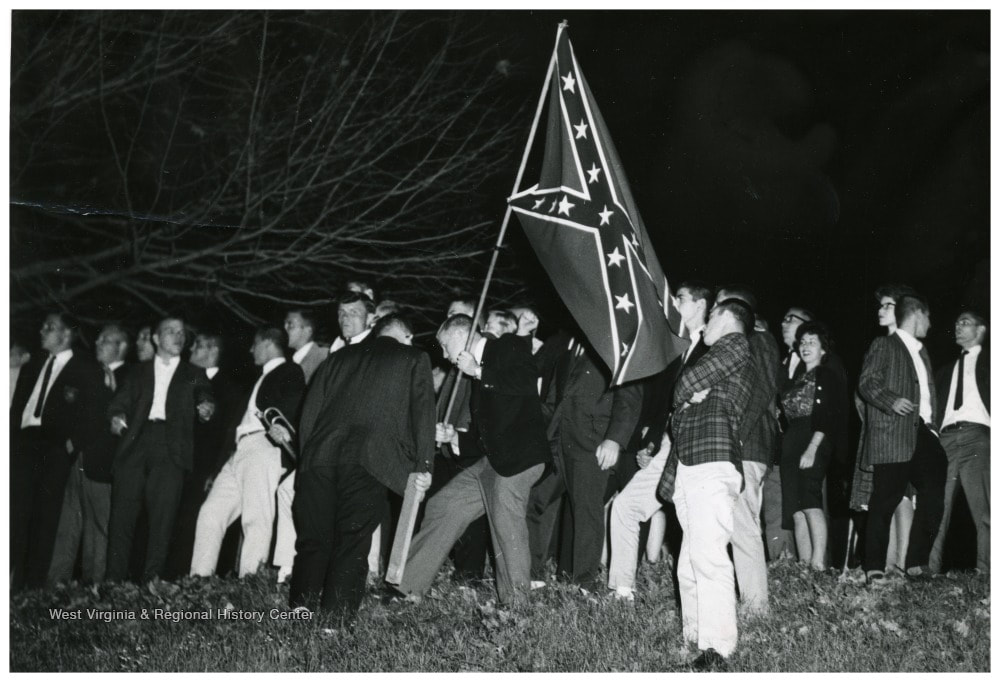

The Reconstruction of our textbooks was an era of military repression imposed on the devastated South by Radical Republicans bent on revenge. Greedy carpetbaggers from the North pushed former slaves into positions of power for which they had no relevant experience. Southern recovery began only after the North finally withdrew its troops. Was it all a pack of lies? No; it was partly true, but not the whole truth. We viewed that era through the lens of poor Appalachian whites, resentful of Virginia’s ruling plantation owners. The lens of former slaves scarcely occurred to us: their urgent search for loved ones sold away under slavery, their thirst for education, their pursuit of opportunities, their hopes raised and later dashed. To tell the whole truth is impossible. Life is too short, and you'll always have a selective lens. Which omissions matter? Perhaps the test of what you leave out is what happens when you add it back in. Does it merely add detail to the picture you already had, or does it change how you see the picture overall? In the case of Reconstruction, I am past due for a different set of lenses, or perhaps a whole new prescription. Images: (left) ruins of Richmond after the Civil War; (middle) Thomas Nast cartoon of a carpetbagger; (right) fraternity raising Confederate flag at West Virginia University, 1967. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed