|

Inspiration doesn’t bubble up when you’re sick as a dog. Granted, my current bug is respiratory, not gastrointestinal as the phrase might suggest, but even so—why dogs? Do they get sicker than the rest of us, or more often?

“Sick as a dog” is said to go back at least to 1705, though I haven’t found the reference yet. Oxford English Dictionary, anyone? According to the OED, early phrases and proverbs smeared dogs as vicious, miserable working beasts that spread disease. Who doesn’t love a good origin story? We thirst to know how a word, phrase, belief, cultural practice, or epidemic began. When evidence runs out, make something up. It stretches the imagination and generates hypotheses to explore. Just remember to distinguish evidence from speculation or hypothesis, to avoid getting mired in conspiracy theories not fit for a dog.

9 Comments

Divorce was unknown among the parents of my childhood friends, though one said hers planned to break up after their kids finished high school. Gays and lesbians were deep in the closet. Yet even in that traditional time and place, not all families fit the storybook image of mother, father, and one to four children. Playmates had lost fathers to war, illness, or construction accidents. Aunts and uncles took in three boys whose widowed mother died of breast cancer. “Traditional families” are not universal, and they never have been.

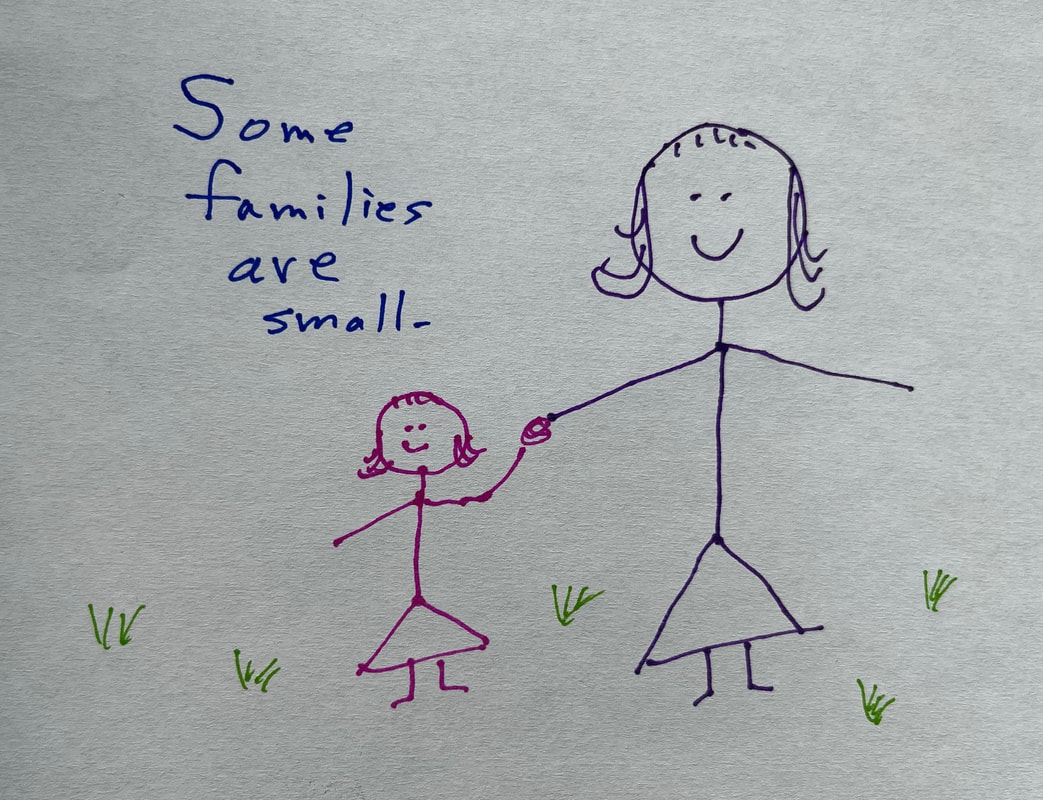

Regardless of talk of death, divorce, or same-sex relationships, early childhood is not too soon to end the false distinction between “normal” and “different.” I’d like to see a picture book something like this: What Makes a Family?

Last week I wrote about parental rights in education. Like religion, partisan politics has no place in grade school classrooms. That becomes complicated when everything from health to climatology gets politicized. Is anything still nonpartisan enough to teach?

Take, for example, the ability to refrain from temper tantrums and play well with others. Parents lambaste school boards about Social & Emotional Learning (SEL) and its five core elements:

Controversial? Really? Though specific SEL programs are up for debate, school involvement in character development is as old as the hills. My grade school report cards rated citizenship as E (excellent), S (satisfactory), or U (unsatisfactory). My ninth grade English teacher stressed moral lessons in every story or poem. High school science labs demanded effective teamwork. If teachers were barred from influencing behavior, classroom management would be impossible, and academics would fall apart. My bias favors parental rights in how we raise our children. No one but me should decide when they’re old enough to play unsupervised; no one knows my kids better than I do. Schools have no place in religious training. Don’t dictate which books to withhold from my child. Whatever my opinion of spanking, parents need broad discretion to discipline their children.

We count on schools to provide the grounding for constructive participation in the adult community. Everyday life works best when most people can read, write, add, and subtract. We’re a healthier society if kids at puberty know where babies come from. It’s in the public interest for citizens to learn the basics of history, government, and science before they reach voting age. My issue with “parental rights” is, which parents? According to the Parents’ Rights in Education website, “PRIE strives for the return of community values properly represented and reflected in school policies.” That’s to say, they want policies to reflect the traditional views of the majority, or the loudest voices. The parental values I favor are individual, expressed family by family. Whether they are minority or majority views is irrelevant. School policies should leave those decisions to me, and so should other parents. First of a three-part series. Next week: Social and Emotional Learning. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed