|

I hear it every day: Viruses are said to mutate naturally toward milder forms that spread more readily, like Omicron. That never made total sense to me. Mutations are like random typos in a genetic code. The longer a virus circulates, the more it can mutate. It might do anything. What it “wants,” i.e. what promotes its survival, is to circulate and replicate instead of dying out.

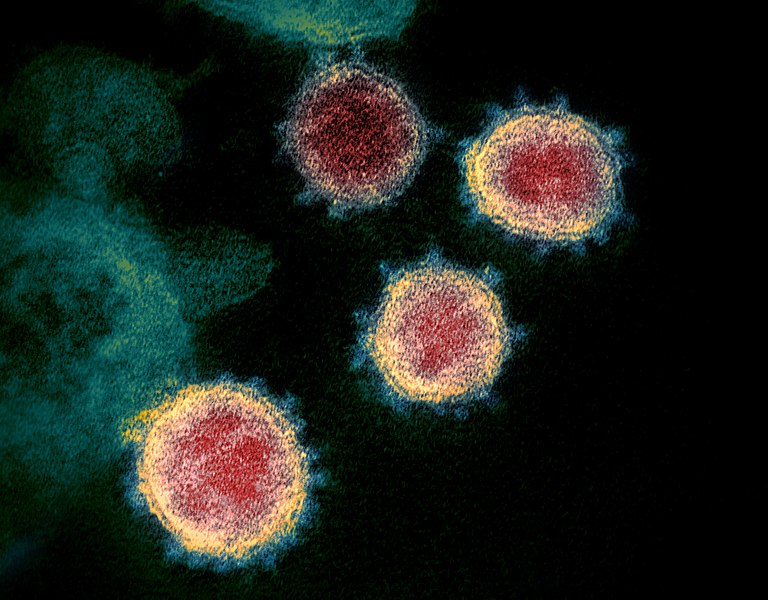

Compared to earlier forms of Covid-19, Delta is more transmissible and more likely to cause hospitalization and death. There’s no inherent tradeoff. Let’s separate the two traits to disentangle science from hearsay. Transmissibility. Most of the millions of coronavirus mutations have little effect or die out quickly. Any with potential must compete with other variants to spread farther and/or faster from the mouth or nose. So yes, it’s true the more transmissible variants will overtake the rest, as we saw with Delta and then Omicron. The virus “cares” most about success in the upper respiratory tract, where it is otherwise pretty harmless. Severity. Coronavirus needn’t infect your lungs to multiply and spread, but that doesn’t bias it to avoid them. It doesn't care about lungs one way or the other. We care, though, because the lungs are where Covid can turn deadly. To believe spreading faster means growing milder is wishful thinking. If I had to guess, I’d suggest variants will be prove more severe in some years than others. But no one knows. Random mutations are a crapshoot. For more, read NPR or watch WHO. Image: Electron microscope image of SARS-CoV-2, Wikimedia Commons.

1 Comment

Strolling in Pasadena last week, soaking up southern California sunshine, I happened on a pair of nine-foot-tall bronze sculptures across from City Hall. I knew of baseball legend Jackie Robinson but not his older brother, Mack (right).

Born to Georgia sharecroppers, the boys grew up in Pasadena. Mack set junior college records in track and field. After local businessmen paid his train fare to the trials in New York, Mack became one of eighteen Black athletes on the 1936 U.S. Olympic team in Berlin. He broke the previous Olympic record in the men’s 200-meter event, finishing just four-tenths of a second behind Jesse Owens. He said of his silver medal, “It’s not too bad to be second best in the world at what you’re doing.” Mack came home to little acclaim. “If anybody in Pasadena was proud of me, other than my family and close friends, they never showed it,” he said. He campaigned for neighborhood improvement and supported his family by sweeping Pasadena streets. That job ended when the city fired its Black workers, allegedly in reprisal for a court order to desegregate public pools. Popular history highlights a few big names and tends to forget the rest. Jackie Robinson and Jesse Owens deserve their fame in the annals of athletics and race. I’m glad Olympic medalist Mack Robinson is finally getting some recognition too, at least in his hometown. Don’t get me wrong. I’m a great fan of science. If its findings keep changing, that’s because scientists are doing their job by learning more each day. Individuals and policy makers are wise to take the latest science into account; but they can’t follow science alone to reach a decision. To ask Dr. Fauci, the CDC, or your doctor for guidance based exclusively on the science is to ask the impossible.

Choices involve values and priorities. At this posting I am in California for family. It’s not an ideal time for air travel, given the Omicron surge. It is the best time to see the people I’m with for the week. Science informed my choice of mask and my actions in airports to minimize risk. What it couldn’t tell me was whether to make the trip. When betrayed by men they trusted, women long ago had fewer options than today. In Sarah Penner’s bestseller The Lost Apothecary (2021), three female narrators take control of their lives in suspense-filled narratives that weave into one.

Nella, a London apothecary in 1791, sells exclusively to women to resolve such ailments as menstrual cramps or unfaithful husbands. Twelve-year-old servant Eliza, who visits the shop for poison on behalf of her mistress, pleads in vain to become Nella’s protégé. Caroline, a present-day American vacationing alone in London after learning of her husband’s infidelity, finds an old vial in the mud. Following clues that lead her gradually to Nella and Eliza (and, at one point, almost to prison), Caroline rediscovers her passion for history, abandoned in the mud of her role as supportive wife. Constant surprises in both the apothecary’s tale and Caroline’s detective work kept me turning pages from the day this book appeared under the Christmas tree. Friendships among the complex characters reveal strength and resilience. It’s a perfect read for a lover of historical fiction, mystery, or both. What are you reading these days? Were your holidays quieter than usual this year? Each time we plan to travel or gather, another variant comes along. Happily, Santa and the public library kept me well set to escape without going anywhere.

The bubonic plague decimated Florence, Italy, in the spring and summer of 1348. In Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, written over the next five years, ten young people escape to a country house after their relatives have died or fled. To pass the time, the ten dance, sing, and tell the hundred stories that make up most of the book. Escapism gets a bad rap, sometimes well deserved. Boccaccio describes Florentines who escape into debauchery, going from tavern to tavern for wine and sex. Others abandon even their children, caring only for personal safety. But the ten wise storytellers escape by finding safe, shared pleasures in a situation they can’t otherwise control. Sing and dance, tell or read stories, watch television or solve jigsaw puzzles. Sometimes escaping is the best you can do. Image: Franz Xaver Winterhalter, The Decameron, 1837. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed