|

Vladimir Putin says Ukrainians and Russians have been one people since the early Middle Ages, when Kyiv was a Russian capital. Ukrainians say after centuries of rule by Mongols, Poles, and Russians, their time has come for self-rule. Putin in turn claims Russians in Ukraine need protection. It's all colored by the ambiguous ideal of one nation, one state.

The notion that each people should govern itself seems so obvious that it’s hard to realize it’s relatively new. As late as 1914, in central and eastern Europe and beyond, most folks lived in multi-ethnic empires. Rulers and nobles might speak one language, urban merchants a second, and peasants a third. This began to break down in the 1800s as social mobility increased. Small principalities combined to form German and Italian nation-states. Ethnic minorities in the Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman empires pressed for autonomy. Then a Bosnian Serb nationalist shot a Habsburg archduke and set off World War I. After the war, a new map of Europe broke the old empires into smaller states based on language, ancestry, culture, and religion. Each people would rule itself. Trouble is, barring isolation or genocide, populations mix. To create ethnic majorities is to create new minorities. They too may demand independence, in smaller and smaller units. The century since World War I has been filled with ethnic conflict. If ethnic self-determination doesn’t bring unity and a sense of belonging, what does? For Ukraine, I'm at a loss. For the U.S., the best I can suggest is a shared national culture based not on ancestry but on our founding principles, such as equality under the law, a free press, due process, and the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

2 Comments

When this question first puzzled me weeks ago, I didn’t realize how many assumptions it holds. That empathy is a gift to the person whose feelings (real or imagined) one feels vicariously. That it is always desirable, at least to that person. That it is either earned by merit or a basic human right. The more I think about it, the more complicated it gets.

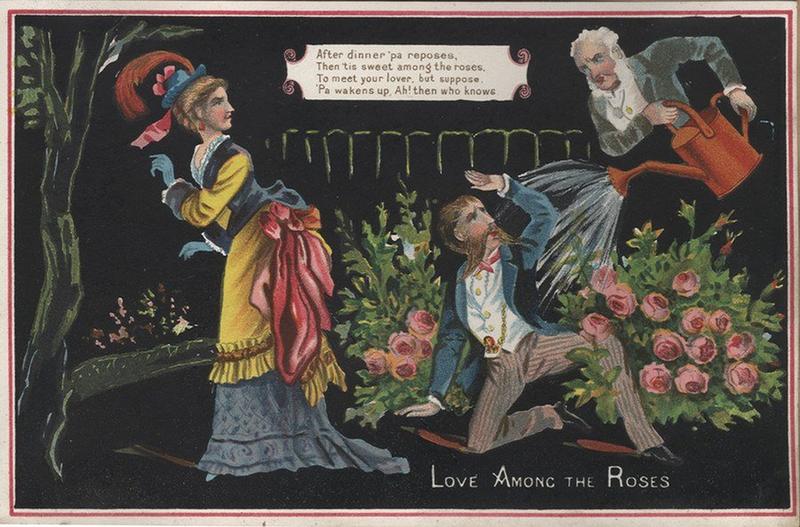

The capacity for empathy is innate, one of many unconscious ways we copy those we interact with. Babies cry when they hear a baby cry. Dogs bark when they hear a dog bark. Empathy helps us learn from each other’s experiences, predict others’ behavior, and cooperate. In evolutionary terms, passing on the relevant genes depends more on empathy’s survival value for empathic individuals and communities than for the people whose feelings are mirrored. Even so, empathy is not always helpful. I don’t want to empathize with the hater or promoter of unfounded fear. Parents calm an anxious child by not getting anxious themselves. I’d prefer my surgeon pain-free and focused, even when I’m distracted by pain. Caring, yes. Understanding, yes. Recognizing another’s humanity, yes. But whether or not empathy is appropriate in any particular case may have nothing to do with deserving. Image: William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Les Noisettes (The Nut Gatherers), 1882. Detroit Institute of Arts. Anonymous, cruel mockery masquerading as humor didn’t start with social media. A surge in mass-produced valentines in the 1800s, prompted by cost-saving innovations in color printing and postage, included not only hearts-and-lace romance and light whimsy but pain-inflicting nastiness. Unsigned cards mocked gender roles, grandiosity, morals, ethnicity, physical traits, social class, or lack of a spouse. Although numerous, they make up only a small proportion of the Victorian valentines left to us today. Most recipients tore them up or burned them.

“Can’t you take a joke?” is one of my least favorite remarks. It allows no response; if you disagree, you’ve proved the point. On the other hand, affectionate teasing and banter can be welcome. How do you draw the line? Avoiding anonymity may give the surest clue. To paraphrase the old saying, if you can’t say something with your name attached, don’t say anything at all. Behind my childhood home lay a vacant wasteland, crossed by a creek. Too low to build on, at least part stayed dry enough for pickup softball. It was a children’s paradise. Last time I went back, tidy backyards extended deep into our one-time paradise to meet the equally deep backyards of houses the next street over. Had any of our lowland been marshy? Was it drained to increase property values? I’ll never know.

Watching lectures on ancient Mesopotamia this winter, I’m learning how marshes around the lower Tigris and Euphrates supported a culture of fishing, water buffalo, and reed structures. That got me pondering marshes and former marshes in my life. Chicago was built on a marsh. My research in the Indiana Dunes began with the historical effects of agricultural drainage ditches. Drainage by humans reduced Earth’s marshland over centuries. Six U.S. states lost 85 percent of their original wetlands. That’s both good and bad. Drainage saves lives by eliminating breeding grounds of the mosquitoes that carry malaria, and by reducing cholera and schistosomiasis. Opening new farmland increases the food supply. But recent efforts to preserve marshes reflect rising awareness of their benefits, such as protecting wildlife and buffering hurricane storm surges. Marshes have long sheltered rebels and outlaws, from the Seminole in Florida to a fictional escaped convict in The Hound of the Baskervilles. Saddam Hussein in the 1990s diverted water from the Mesopotamian marshes, allegedly for farming and disease control, but more to force out Shi’ite guerrillas and the “Marsh Arabs” who supported them. Despite some recovery since Hussein’s ouster in 2003, Iraq’s marshes—like wetlands around the world—appear destined for the losing side of history. Image: Horicon Marsh, largest freshwater cattail marsh in the United States, near my Wisconsin home. Photo by Allen C. of Prairie du Sac, 2008. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed