|

Few hikers are on the Cross Plains segment of the Ice Age Trail at Hickory Hill, each a solitary walker like me. Our interactions are all the same. Without stopping, we step to our respective sides of the trail and say hello. They say, “Beautiful day, isn’t it?” or “Lovely day for a walk,” I concur, and we continue on our ways.

Years ago, in my study of Romani (Gypsy) culture of the horse-drawn-caravan era, one source said the Roma didn’t routinely comment on the weather. What’s the point? Anyone can see whether it’s sunny or raining. So why do we mention it so regularly? To stay civil toward a neighbor or cousin whose opinions annoy us? To defer a difficult conversation? To tune out others, like Mabel’s sisters in The Pirates of Penzance, who shut their eyes and talk about the weather to allow her new romance some privacy? Although avoidance can be a motive, weather talk often expresses something more positive. A friend used to describe “Nice day!” as meaning “I see you. Do you see me?” I’ll go one step further. It’s a celebration of what we have in common, too rare in these days of defining ourselves and others by our differences. Sure, how someone votes or worships or feels about masks is part of who they are—but so is their love of dogs or sweet corn or the rustle of autumn leaves. For those of us on the trail in this moment, what binds us is our shared delight in a lovely September day.

4 Comments

In April 1861, President Lincoln asked states to provide militiamen for three months to put down a rebellion. Kaiser Wilhelm II in August 1914 told departing troops, “You will be home before the leaves fall from the trees.” U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said of conflict in Iraq in early 2003, “It could last six days, six weeks. I doubt six months.” Each of those wars raged four years or longer.

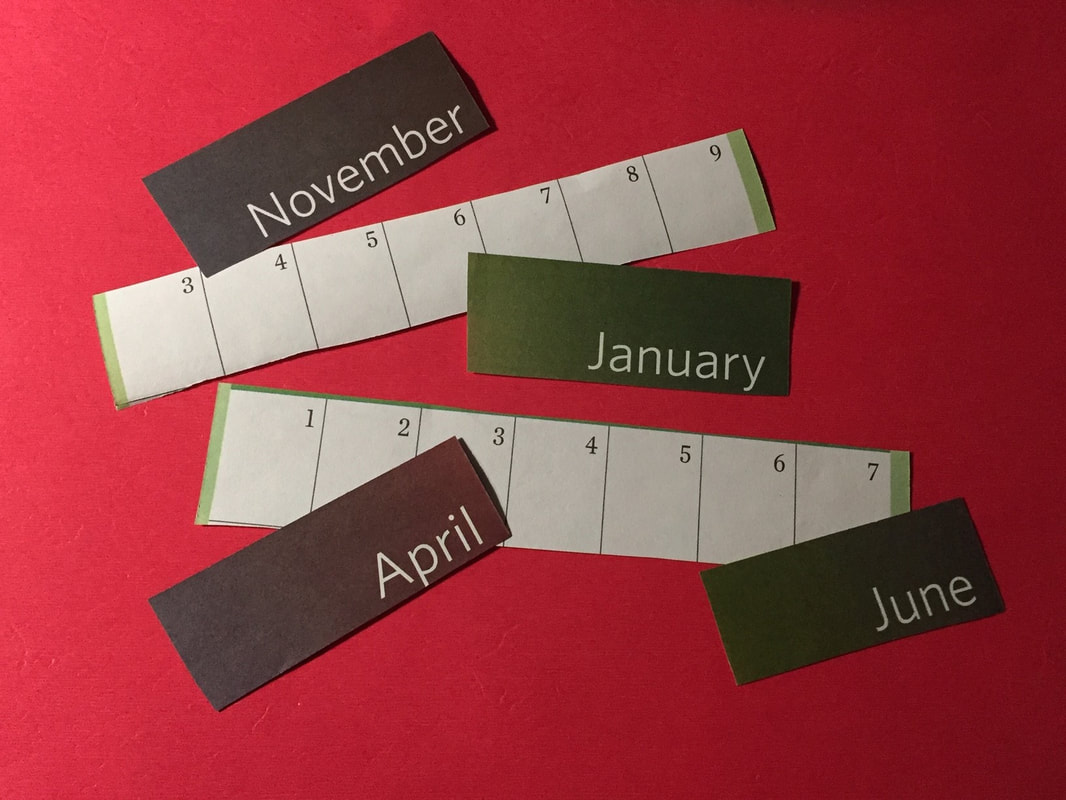

The point isn’t that calamities drag out; the Gulf War of 1991 took only weeks. The point is that we can’t predict without a crystal ball or benefit of hindsight. Faced with Covid lockdowns in March 2020, I stocked up on canned goods in case this might continue all the way till June. By fall, that first illusion shattered, we spoke of getting back to normal soon after we had a vaccine. Summer 2021 looked promising until Delta came along. What next? Covid-19 impacts more aspects of more Americans' lives more dramatically than any other crisis in my lifetime. Now as on the home front during World War II, resources are mobilized, events canceled, and travel restricted. Jobs are reshaped, office work done from home today, factory work done by women back then. Our supply chains are disrupted; their gasoline, butter, and sugar were rationed. We wear face masks; my East Coast parents hung blackout curtains. Will the disruption go on for months? For years? Our World War II forebears had no way to know. Neither have we. The first holiday of the Zurich, Switzerland, school year is Knabenschiessen-Montag.

“What?” I look up from the calendar, recalling too many American school tragedies. “Boy Shooting Monday?” My translation is correct, they tell me, but the term is misleading; for the past thirty years, Zurich’s annual teen event has also involved girls. For boys, the shooting contest goes back at least to 1656 and was formalized in the late 1800s. Normally it’s preceded by a public festival the second weekend of September. This year the festival is cancelled for Covid, but Monday’s shooting will go ahead. Schools close for the day. Many workers get a half day off. Switzerland has a high rate of gun ownership but very little gun violence, with no mass shootings since 2001. Privately held guns are strictly regulated. Mandatory military service for men ensures training. Switzerland shows a healthy gun culture is possible. Whether it is possible in the United States, I am not so sure. Last week I returned to Wisconsin’s Door Peninsula after several years away.* Despite Covid-19, vacationland looked as busy as ever. Americans still travel but differently, choosing road trips over flights, short-term rentals over hotels, outdoor recreation over urban crowds. Door County fills the bill with its miles of shoreline, hiking trails, and accessible location. Restaurants and their patio tables were packed by Saturday noon.

And yet, the restaurants are hurting. I found longtime dinner favorites open only on weekends, or only for breakfast and lunch. The limiting factor is not customers but staff. I saw few of the eastern European students on J-1 exchange visitor visas who usually help fill Door County’s seasonal openings. A frustrating quest for Monday supper ended well with locally caught whitefish at the non-touristy, non-seasonal Cornerstone Pub in Baileys Harbor. “Monday is our pot-roast special,” the waitress told me. “If we closed Mondays, we’d have a riot on our hands.” I wonder if the labor shortage so evident to me last week will have any lasting effect. In medieval Europe after plague decimated the workforce, peasants were able to negotiate better terms. Landowners converted labor-intensive cropland to sheep pasture, and the wool industry boomed. Will Covid-19 reverse decades of low-end wage stagnation? Will some industries shrink and others flourish? One way or another, the natural beauty of Door County will keep attracting visitors like me, and local businesses will find ways to keep us feeling welcome. *For earlier visits, see “Up North” (2016) and “Up North, Revisited” (2018). |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed