|

If only I had gotten that surgery years ago. What if I hadn’t seen the child run into the street? Human minds love to imagine a past or present world much like the real one, with one key element changed. It’s one way we learn from experience. It may also mire us in remorse or self-pity, unable to move forward.

Over a balmy California outdoor dinner, a philosopher and a brain scientist discussed David K. Lewis’s classic example: "If kangaroos had no tails, they would topple over” (Counterfactuals, 1973). What does it mean to make a factual statement about a situation that is contrary to fact? Why do we so often describe the world we know by comparing it to one that doesn’t exist? In a recent thought experiment, I’m trying to replace negative statements like “It isn’t cloudy or cold” with affirmatives that mean the same thing: “It’s sunny and warm.” The editor in me tweaks “I can’t get that app to load” into “How to load that app is a mystery to me.” With each switch, my spirits lift. It’s as though the negative wording suggests an imaginary, alternative, cold and cloudy world in which apps load easily every time. In the affirmative, the only world I need is here and now.

2 Comments

Major Grey’s chutney. Earl Grey tea. The terms are generic, not brand names. They conjure up the 1800s, when English merchant ships plied the seas and the sun never set on the British Empire. Any relation between the chutney or tea and the men they’re named for is shrouded in legend.

Major Grey’s chutney. A sweet and sour relish made with fruits or vegetables, vinegar, sugar, and spices, chutney has been savored in India since ancient times. It takes many forms. Tradition says Major Grey, a 19th-century British officer serving in the Bengal Lancers in India, developed the mango-and-raisin version that bears his name. London condiment company Crosse & Blackwell began to produce it, and others followed suit. Major Grey’s became especially popular in the United States, likely because it is sweeter and milder than most authentic Indian chutneys. As for the major, there’s widespread doubt he ever existed. Earl Grey tea. Charles Grey, earl and British prime minister 1830-34, never went to China. The earliest known English reference to flavoring Chinese tea with oil from the rind of a bergamot orange is from 1824, in a complaint about using bergamot to cover the taste of low-quality tea. Lore linking the two include that the earl received the bergamot recipe as a thank-you gift from a Chinese tea master; that his wife and/or the later Queen Victoria loved it; that bergamot offset the flavor of well water on the Grey family estate; and that Earl Grey gave the recipe to a partner of the tea company Jacksons of Piccadilly (now Twinings). Editors of the Oxford English Dictionary, unable to find “Earl Grey tea” in print before the 20th century, appealed in 2012 for any earlier references to the term. Contributors found ads from 1884 for “Earl Grey’s mixture.” Sources from the 1850s and 1860s mention “Grey’s mixture” or “Grey’s tea,” perhaps with reference to tea merchant William Grey. The title of nobility may just be a later marketing ploy. Image: Thomas Goldsworth Dutton, East Indiaman sailing ship Madagascar, built 1837. National Maritime Museum Greenwich, London. Even before war with Russia, polio was creeping back into Ukraine. Last fall it paralyzed a 17-month-old girl in the northwest. Next it struck a two-year-old boy in the far southwest. Contacts tested positive. Because poliovirus is highly contagious and usually asymptomatic, one case signals a crisis. Polio cannot be cured, only prevented.

The culprit was not naturally occurring poliovirus, which circulates only in Pakistan and Afghanistan, but a mutation of a vaccine component that had passed from person to person. Counter-intuitive as it seems, the way to stop vaccine-derived polio is more vaccine. Mutation to a dangerous form takes months. In a well-vaccinated population, the weakened virus in oral polio vaccine dies out for lack of susceptible people to host it. Immunization rates in Ukraine were unfortunately low. Health authorities in Ukraine, already struggling with a Covid surge, launched a polio vaccination response in February. War with Russia put the drive on hold. Medical supplies are running out. Bombs and battles shift health workers’ priorities. Massive population movements impede services. Refugees may carry virus unwittingly into neighboring polio-free countries. Do not be surprised if we see more children in eastern Europe paralyzed before this is over. Basic health care is among the many casualties of war. Image: Poster from Ukraine’s previous polio outbreak in 2015. Two years ago, a deadly new virus kept us under siege. Barbershops and hair salons in many areas were shuttered to prevent infection. Even after they reopened, some customers were slow to return. Former clients hacked their hair off at home or let it grow out. When I see someone for the first time in a while, I’m often started by hair halfway down the back or re-styled in kitchen experiments.

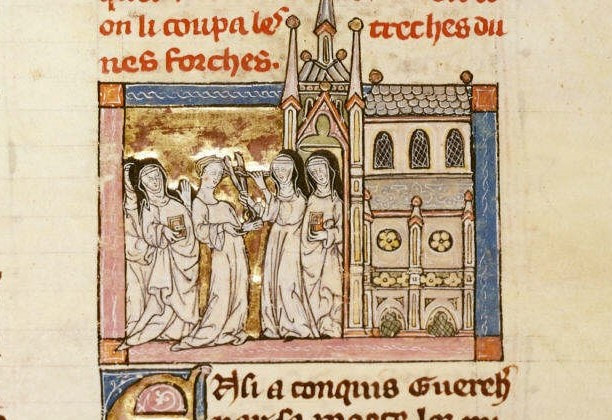

These changes recall my long-ago fantasy of writing a world history based on hair. Haircuts are virtually unique among visual signs of status and identity. A short haircut is the work of an hour but reversing it can take months. That made it a rite of passage for entry into religious orders and armed forces. It could symbolize membership or belonging, commitment, dedication to God or country, and renunciation of worldly vanity. It might distinguish servants, convicts, and pageboys from aristocrats and freemen. Safer than long hair for factory work and street fights, it became a badge of honor for the London working-class youth who started the skinheads. How will a hair-based narrative treat our present pandemic? I can imagine a world where “first haircut” conjures up images not only of small children, but of adults emerging from a period of hunkering down for health. Image: French abbess with oversized scissors cuts the hair from a novice entering the convent. British Library, 1316. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed