|

Pumpkins, autumn leaves, flickering flames, and golden chrysanthemums: Now is when orange comes into its own. Lanterns and bonfires push back against the deepening darkness.

The color got its name from the fruit tree, native to northern India. The Sanskrit name naranga traveled west with the fruit, reaching English as orange by the late 1300s. Sailors planted orange trees along trade routes to prevent scurvy. It wasn’t until the early 1600s that the fruit’s color, formerly called geoluhread (“yellow red”), began to be called orange as well. While seasonal bonfires are an ancient tradition, the prevalence of orange in mid-autumn decorations is distinctively American. Irish immigrants in the 1800s, accustomed to carving turnips for lanterns to ward off evil spirits on All Hallows Eve, discovered North American pumpkins worked even better. The brilliant, spooky orange of glowing pumpkin lanterns against the black of lengthening nights set the ubiquitous color scheme of late October.

6 Comments

The story of Renaissance sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti working for decades on one set of cathedral doors used to boggle me. It no longer seems strange. I’ve been writing Rotary International’s history of polio eradication for a quarter century now, with no clear end in sight.

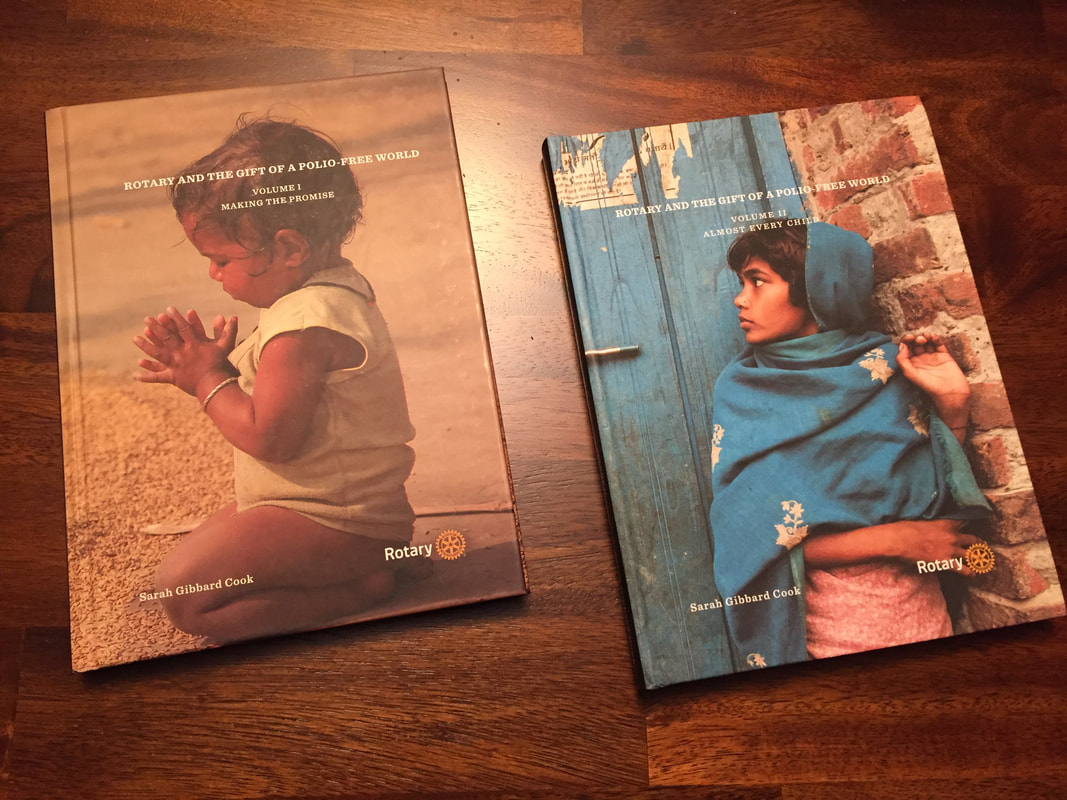

What’s taking so long? The World Health Organization (WHO) eradicated smallpox in eighteen years from the first plan to the last natural case. With one human disease gone forever, WHO, Rotary, UNICEF, and CDC launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988. More than thirty years later, natural poliovirus still paralyzes children in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Perhaps the biggest difference between the smallpox and polio challenges is that smallpox was reliably visible. Its telltale rash let health workers close in on the virus by vaccinating each patient’s neighbors and contacts. Most polio infections are invisible. Poliovirus paralyzes fewer than one in a hundred people infected, so it can spread widely before anyone knows it’s there. Like many projects, polio eradication is taking longer than first envisioned. The work continues, and so does the writing. I look forward to the day I can finish Volume III confident that poliovirus will never paralyze another child. The published volumes of Rotary and the Gift of a Polio-Free World are Vol. I, “Making the Promise,” and Vol. II, “Almost Every Child.” Back in high school and college, friends sometimes set me up on blind dates. Nice guys all, but nothing clicked. How, as a writer, can I set up an enjoyable blind date between reader and character? They’ve never met before the reader picks up the book. My hope is to craft a character with whom readers will click.

Writing advice is clear and consistent: A relatable character needs strengths, quirks, and one fatal flaw. The narrative must carry the main character through an arc of personal growth that involves facing the flaw head-on and overcoming it to do what must be done, revealing a theme in the process. All without coming across as formulaic. I get it, or think I do, up to the moment I sit down to write. Then the questions bubble up: Who among us has one and only one significant bad habit? What’s the flaw for Louise Penny’s Chief Inspector Gamache to overcome, kindness? In an ongoing series, does character arc mean conquest of the same flaw again and again, like Sisyphus’s stone rolling back down the hill? Script consultant Dara Marks defines fatal flaw as “a struggle within a character to maintain a survival system long after it has outlived its usefulness.” Going back to my novel-in-progress, I’ll try stepping away from moral judgments or bad habits to ask what old way of being no longer works in my character’s new situation. Perhaps I might even step away from fiction to ask the same question of myself. What a comfort to be told that what we believe is true! Even if our belief feels unpleasant, to hear it affirmed is somehow to be reassured. In sooth, this affirmation soothes, as any soothsayer might predict.

Sooth and soothe come from the same Old English root. Soth was originally an adjective meaning “genuine” or “true.” The noun form meant “truth”; the verb form, “to verify or show to be true.” Soothe emerged in the 1560s for humoring or flattering others by asserting what they said was true. It denoted the comfort of uncritical agreement, not the pain of truth confronting falsehood. Soothe meaning “to calm gently” appeared in the 1690s, finally detached from any relationship to truth. To learn the error of a former belief is disorienting at best. It may be exciting, it may be distressing, but it rarely soothes. Small wonder we go to such lengths to avoid it. Small wonder our efforts to persuade others (or theirs to persuade us) by facts and logic are often met with deaf ears. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed