|

Two years ago, a deadly new virus kept us under siege. Barbershops and hair salons in many areas were shuttered to prevent infection. Even after they reopened, some customers were slow to return. Former clients hacked their hair off at home or let it grow out. When I see someone for the first time in a while, I’m often started by hair halfway down the back or re-styled in kitchen experiments.

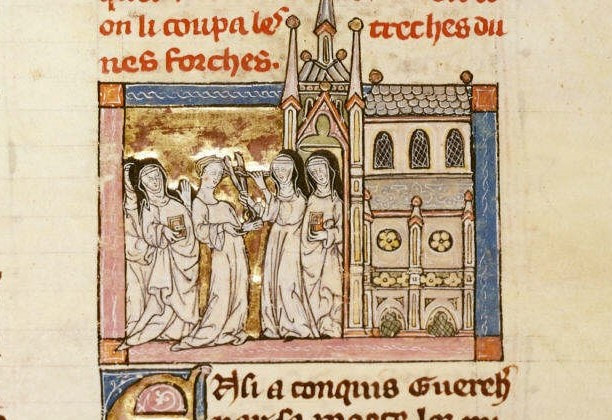

These changes recall my long-ago fantasy of writing a world history based on hair. Haircuts are virtually unique among visual signs of status and identity. A short haircut is the work of an hour but reversing it can take months. That made it a rite of passage for entry into religious orders and armed forces. It could symbolize membership or belonging, commitment, dedication to God or country, and renunciation of worldly vanity. It might distinguish servants, convicts, and pageboys from aristocrats and freemen. Safer than long hair for factory work and street fights, it became a badge of honor for the London working-class youth who started the skinheads. How will a hair-based narrative treat our present pandemic? I can imagine a world where “first haircut” conjures up images not only of small children, but of adults emerging from a period of hunkering down for health. Image: French abbess with oversized scissors cuts the hair from a novice entering the convent. British Library, 1316.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed