|

I wrote my British history dissertation during the Vietnam War. While I pored over 300-year-old documents in libraries and archives, American men were drafted or fled to Canada. Chaos erupted on the streets. Richard Nixon was elected president. My research topic, how Puritan John Owen’s theology shaped his ties to Oliver Cromwell in England’s civil war, seemed far removed from current events; but my findings changed how I see the world.

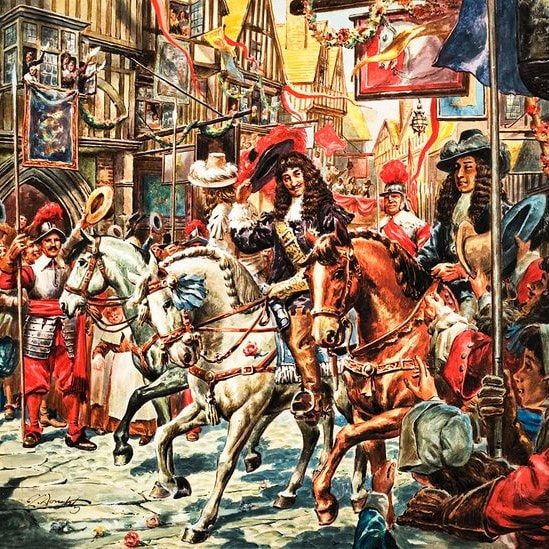

The notion that “the end justifies the means” seemed straightforward. Wasn’t a worthy end the only reason to use any means in the first place? Hey, I was young. On 4”-by-6” note cards, I recorded how Owen defended beheading the King and throwing out one Parliament after another when their actions conflicted with God’s will. In Washington, President Nixon backed a burglary to help him win a second term. In musty archives, I wrote how 17th-century Puritans put England under military rule, and a fed-up nation finally welcomed a Royalist army to restore the monarchy. On the radio over a colleague’s dining room table in 1974, I heard Nixon resign office rather than stay to be impeached. My take-away from Owen’s biography was that process matters more than winning. It is best in the long run to admit the loss of a free and fair election, to abide by legislation we dislike, to uphold the Constitution even when we work to amend it. Yes, some life-and-death cases must yield to conscience, like the Underground Railroad or water in the desert for parched migrants. But to justify win-at-all-costs methods by framing policy debates as life vs. death, socialism vs. fascism, sets everyone up to lose in the long run.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed