|

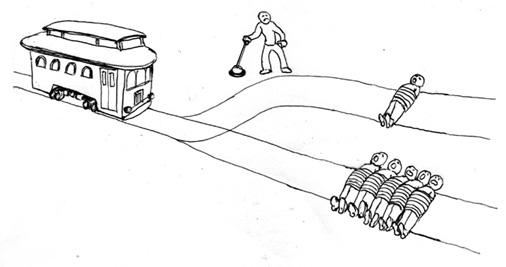

In war, it’s called collateral damage. In medicine, adverse side effects. Few of us would kill one innocent person to save another. Would you do it to save a hundred? A thousand? A million? Moral philosophers call this the trolley problem. If you saw a trolley hurtling toward five people tied to the track, and your only option was to switch it to another track with just one potential victim, would you pull the switch?

We seem hard-wired to accept greater harm from impersonal causes than from human deeds. To ignore preventable storm damage feels less wicked than inflicting comparable damage. Inaction, sins of omission, or leaving matters to nature or chance ranks higher in our moral instincts than committing active harm, however small. Some take it a step farther, calling nature inherently good. Human intervention feels suspect. Before vaccines, polio paralyzed about half a million children a year. Mass vaccination largely eliminated the disease in industrialized countries by 1988, but polio still paralyzed or killed some 350,000 a year in developing countries—a thousand children a day. Mass campaigns with a cheaper, easier-to-administer oral vaccine eradicated two types of naturally occurring polio and reduced the third type to only 6 cases in 2021 and about 30 this past year. But 2022 also saw between 500 and 600 children paralyzed by polio that could be traced to mutations in that same oral vaccine. A new, more genetically stable vaccine should resolve this problem. Meanwhile, which is worse: hundreds of children paralyzed because of indirect human action, or hundreds of thousands paralyzed naturally whom humans could have saved? It’s a real-life version of the trolley problem. Which alternative shocks you more? Which keeps your child safer?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed