|

Last week, three near neighbors whose homes back onto a natural resource area woke to find their birdfeeders and trash bins ravaged. No mere raccoon was strong enough to bend the poles and chew through the feeders. We had a bear in the neighborhood.

An estimated 24,000+ black bears live in Wisconsin, up from 9,000 in 1989. Most live in the north, far from us, but their range is expanding southward. They wander in late spring and early summer to find food and mates. In the past few years, bears have been seen in Madison, Middleton, Waunakee, and Windsor, practically shouting distance from my home. How I’d love to see last week’s vandal! Preferably from a distance and through the window. I still recall with delight watching bears as a child in Yellowstone, before the park changed its practices to reduce bear/human contact and resultant injuries. With reluctance, I must admit it’s probably better for the neighborhood if our midnight visitor has moved on. Image: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

4 Comments

“It’s clean-up time! It’s clean-up time! Put all the toys away,” the toddlers sang with glee as they moved playthings from the floor into the toybox. In a few years they’ll be sweeping the porch with child-sized brooms. When will they learn to tell work from play? “Need to” from “want to”? The price from the pleasure?

Work is an activity to achieve a goal or result, or a task that has to be done, or both. But is the difference from recreation so clear? I work in the garden to tidy our grounds, but even more to soak up the long-awaited sun and sweet spring air. Don’t some athletes play in part to reach the finals or earn a college scholarship? Some work is arduous, painful, and unavoidable. Some workers must carry that burden for exhausting hours at a stretch. For others of us, including but not limited to writers and artists, the line between work and play is thinner. In Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, as I recall, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes a building custodian who makes a game of his job by guessing how many minutes each task will take. Next time a week feels encumbered with obligations and appointments, I’ll try to imagine myself an innocent toddler who hasn’t yet tasted from the tree of knowledge of work and play. Memories:

Packaging. Bradford Plumer wrote in Mother Jones (“The Origins of Anti-Litter Campaigns,” May 22, 2006) that industry groups started the anti-litter campaign after World War II to keep consumers buying new goods in disposable packaging instead of refillable containers. This, and resultant state laws, shifted responsibility for needless trash from manufacturers to private citizens. Plastics. Laura Sullivan reported on NPR’s Morning Edition (“How Big Oil Misled the Public into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled,” Sept. 11, 2020) that oil and gas companies knew all along that recycling plastic would cost more than burying it. Plastic degrades after just a few rounds of recycling. With or without the familiar triangle of arrows, nearly all plastic goes into landfills or the ocean. Industry groups still promote recycling because it keeps us buying plastic. Image: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Down the road from my house is Governor Nelson State Park. The wooded hill with its panther and conical effigy mounds, the prairie with its seasonal cranes strutting their stuff, and the Lake Mendota shore make it one of my favorite places to walk. We’d lived here awhile before I realized the park was named for the same Gaylord Nelson (Wisconsin governor 1959-63, U.S. senator 1963-81) who founded Earth Day on April 22, 1970, to promote environmental activism.

In my childhood in the 1950s, “Don’t be a litterbug!” was the message to keep America beautiful. The broader environmental movement began in 1962 with Rachel Carson’s bestseller Silent Spring, which described devastation to wildlife and human health from chemical pesticides. Reducing pollution beyond mere litter was too big a job for individuals alone. A flurry of legislation over the next decade addressed air and water quality, solid waste disposal, and more. Environmental not-for-profits proliferated. Municipalities in the 1970s offered recycling, first at centers and then curbside. Cars were redesigned to run on unleaded gasoline. Gaylord Nelson’s first Earth Day was fueled in part by the shock of oil disasters. In early 1969, the largest oil spill in U.S. history to that time blackened the beaches of Santa Barbara. It killed thousands of birds as well as dolphins, seals, and sea lions. Five months later, an industrial oil slick set Ohio’s Cuyahoga River ablaze. Americans recoiled. In 1970, millions attended Earth Day events and President Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency. Protecting the environment had become a widely shared, nonpartisan value. When I volunteered for the local Token Creek Watershed in the late 1990s, I loved how old-time hunting-and-fishing conservationists and progressive environmental activists worked together to preserve a treasured habitat. As the spotlight shifts from litter to pollution to endangered species to climate change, might we again someday join forces to protect our common good? On April 14, 1935, a cold front blew a massive wall of dust south through Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. The churning blackness towered hundreds of feet above the barren plain. It raced at fifty or sixty miles per hour. A journalist trying to outrun the storm drove with his car door open to see the edge of the road. In an article the next day, he coined the term “Dust Bowl.”

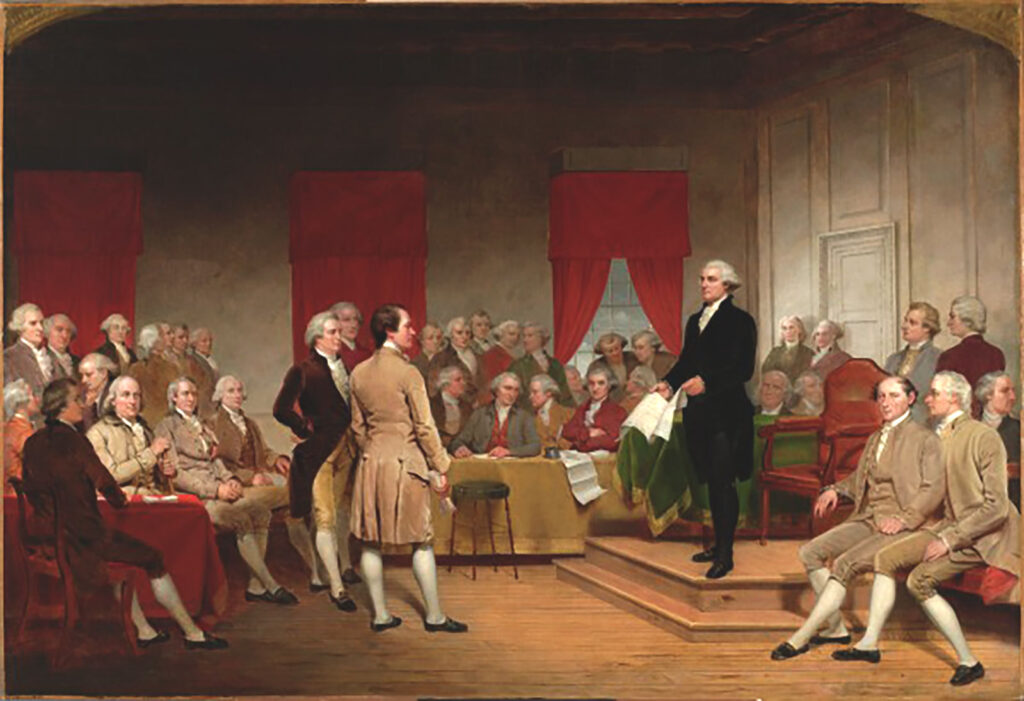

The Black Sunday storm was the worst of several in the Dust Bowl decade, caused by overgrazing and overcropping that left nothing to hold the soil. Millions left the region as farming became impossible. The experiences of people uprooted by the Dust Bowl inspired countless novels for adults, from Grapes of Wrath (John Steinbeck, 1939) to West with Giraffes (Lynda Rutledge, 2021). Reading Blue Willow (Doris Gates, 1940) was a significant influence in my childhood. It tells of migrant farm workers in California: Dust Bowl refugees Janey Larkin and her parents from Texas, and Janey’s friend Lupe Romero from Mexico. Written by a librarian who worked with migrant children in Fresno, the book drew criticism from some who disapproved of stark realism in stories for children. Unaware of any controversy, I was utterly fascinated and engaged. Like books set long ago or far away, Blue Willow fed my lifelong curiosity about lives very different from my own. It introduced me to children in my own country, in more or less my own time, with lives every bit as unfamiliar. I’d seen Appalachian poverty and outmigration to industrial cities like Akron or Baltimore, but migrant farm labor was a whole new world to me. The Dust Bowl added another piece to the puzzles I’ve been assembling ever since. Image: The Black Sunday dust storm approaching Spearman, Texas on 04/14/1935. The National Archives. Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

- United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 2 “All other Persons” meant slaves. Three-fifths of a person! The Framers built racism into our very Constitution by declaring anyone who is enslaved to be less than fully human! As we often hear, the very idea is demeaning. It may seem counter-intuitive that proponents of slavery wanted to count enslaved and free persons equally, while anti-slavery delegates would rather have reduced three-fifths to zero. The negotiators of the Three-Fifths Compromise weren’t as interested in the very idea as in practical results. Including the whole number of slaves would increase the voting power of slave states in Congress and in presidential elections. Omitting them altogether would weaken it. Condoning slavery at all was of course racist and demeaning, as were some comments made during the debate. That said, if you were voting in 1787 but with your present values, what fraction of a person would you have voted to count someone who was enslaved? Image: Junius Brutus Stearns, Washington as Statesman at the Constitutional Convention, 1856. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. One day long, long ago, when I was a summer camp counselor for a cabin of junior-high-aged girls, my campers short-sheeted my bed. This classic practical joke involves making a bed with one sheet doubled back so the occupant can’t straighten her legs. When I climbed under the covers and got trapped in the sheet, I burst out laughing. I’d once been a camper myself.

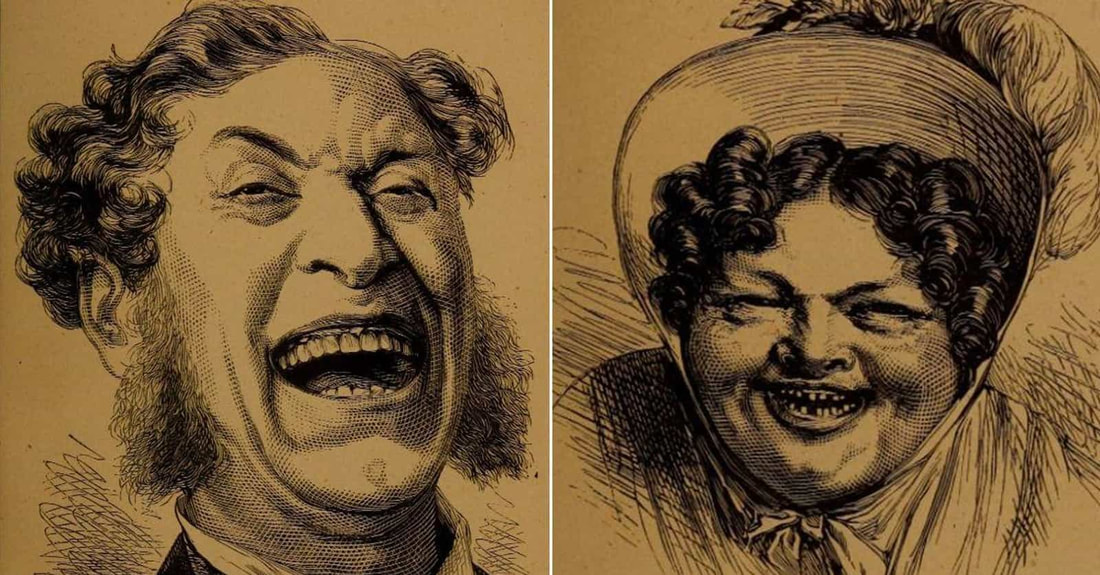

One reason their trick was fun for us all was that the girls knew me well enough to know I’d enjoy it. One person’s friendly tease is another person’s harassment. “Can’t you take a joke?” is right up there with “You’re in denial” on my list of obnoxious things to say; to disagree just proves the speaker’s point. “Just kidding” claims a free pass for anything, however offensive. It frames pushback as humorless literalism. Nothing against healthy laughter, friends. But unhealthy laughter is becoming more dangerous as traditional norms of civility break down. Actual beliefs or intentions masquerade as jokes. Mockery is dehumanizing. April 1 is a day for innocent fun. Words and deeds that aren’t innocent don’t become so by calling them jokes. Image: George Vasey, The Philosophy of Laughter and Smiling (1875). Vasey considered roaring with laughter a vice of the depraved, dissipated, and criminal. Happy New Year! In medieval Europe, the Christian era (and each year within it) began the day the Angel Gabriel told Mary she would become pregnant: March 25, Lady Day, exactly nine months before Christmas. Split between two years, March counted as the first month on the Julian calendar then in use. That made September, October, November, and December months seven through ten, or septem, octo, novem, and decem in Latin.

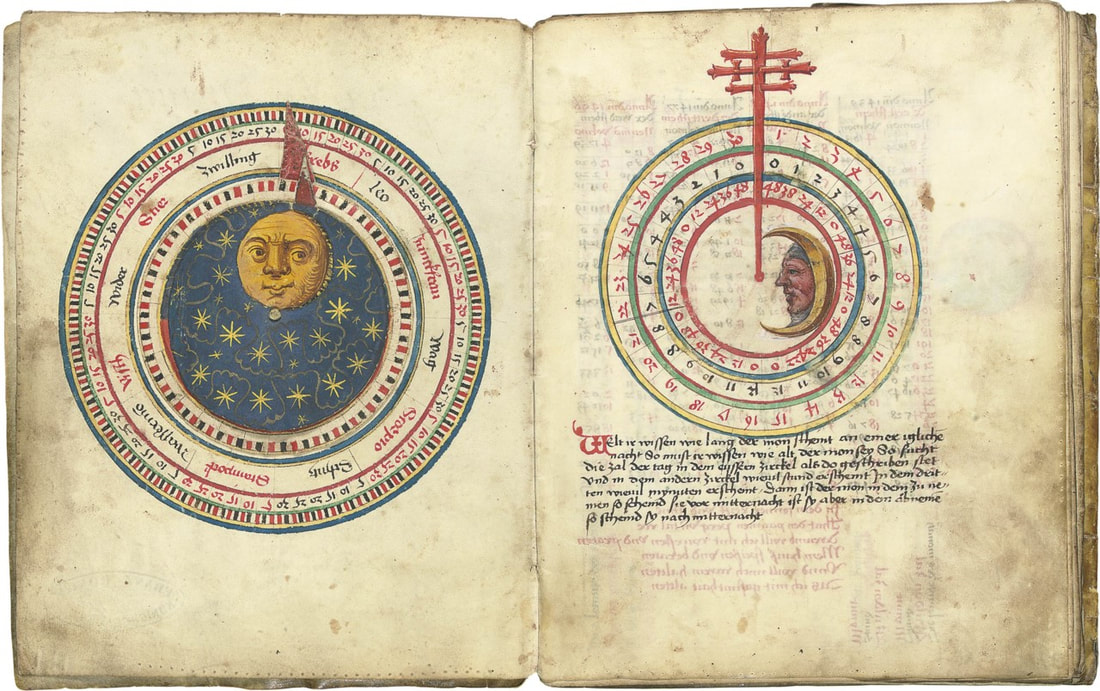

A slight miscalculation of leap years gradually threw that calendar out of sync with nature and the sun. By 1582, it was ten days off. That year Pope Gregory reset the calendar to scrap the ten extra days, start the year on Jan. 1, and fine-tune the leap year formula. Human nature and politics haven’t changed much. Then as now, anything my rival or enemy proposes, I must reject. While Roman Catholic countries promptly adopted the Gregorian calendar, Protestant nations decried it as popish. Britain and its colonies kept the archaic one until 1752. March 25 remained the legal first day of the year, while some began to greet the new year informally in January. Imagine historians interpreting English sources from the 1600s. Was a letter dated March 10, 1668, written before or after one dated November of that year? The ten- or later eleven-day difference between England and most of the Continent muddied diplomatic correspondence. Imagine George Washington revising his date of birth from Feb. 11, 1731, under Britain’s old calendar to Feb. 22, 1732, under the new one. He celebrated both birthdays to the end of his life. Image: Johannes Von Gmunden, calendar, 1496. I’m home from vacation and down with a cold. The laundry is washed and the mail sorted. Now I want to do nothing but read and sleep until the sniffles dry up.

Do you ever wonder how hard to push yourself? Grit involves the self-discipline to persevere now for future success. Delayed gratification is about putting off a pleasure now for the sake of a larger reward later. Skip that cake if you’ve started a diet. On the other hand, consider the workaholic business executive saving up toward a peaceful retirement of fishing and hiking. Why not fish and hike more now and retire with adequate but modest savings? Surely it depends on the person, the situation, and the day. Too much stress is bad for blood pressure and the heart. Too little stress gets nothing done. I try to think “choose to” instead of “have to.” I’m happier with clean clothes and a clear desk, but I choose to wash dishes by hand rather than replace the broken dishwasher until I have more energy. How do you decide how hard to push? Cool ocean breeze. Sun warm on the face. Roar of crashing waves. Pacific Beach in San Diego is a feast for the senses even when I close my eyes.

Last time I visited this city, I loved the stimulation of exploring a different tourist site each day. This time my travel companion and I rarely ventured more than a block from the beach. Watching her frolic in the sand as she did long ago, growing up by Lake Michigan, I realized vacations aren’t just about novelty. They’re also about ways new discovery intertwines with the deep comfort of the familiar. To revisit happy childhood memories warms the spirit. To start and end a vacation day with rituals from home sets a framework for the excitement in between. To re-enter an eatery I first tried yesterday begins to feel like home today when the server welcomes me back. I’m learning to appreciate both the adventure and the comfort, and the ways each enriches the other. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed