|

Names matter. Some traditions endow them with magical power, as in the Rumpelstiltskin tale. A new name on entering a religious order can signal a change in status. Companies and not-for-profits rebrand themselves. Individuals change names to better match their sense of self. I try to call people what they prefer, short of “Your Majesty” or “My Lord and Master.”

Fresh sensibilities set off a flurry of renaming. Forts Benning and Hood, named for Confederate generals, are now Fort Moore and Fort Cavazos. In the food aisles, Aunt Jemima is now the Pearl Milling Company, and Eskimo Pie is now Edy’s Pie. The former Redskins are now the Washington Commanders; the former Cleveland Indians, the Guardians. Debate rages case by case over whether historical figures who held slaves should be deleted from institutional names. Names trigger bias even in the well-intended. Faculty evaluations of fictitious applicants Karen and Brian differed on otherwise identical resumes. A friend with a Scandinavian name is abashed to be treated better than her sister, whose name sounds more stereotypically Black. When I changed from a “Miss” to a “Mrs.” long ago, I was startled by the deep chagrin of any who used the wrong term. They seemed to think they’d insulted me. Birds won’t notice when the American Ornithological Society assigns descriptive English names to dozens of species in place of terms referring to people. Birdsongs won’t change, but listeners might. Would a rose renamed “garbageweed” still smell as sweet? That depends on the person doing the smelling. Image: Long-tailed duck, Wolfgang Wander, 2006. Called derogatory “oldsquaw” in the 1900s.

6 Comments

Another turkey day has come and gone. What’s weird about a President pardoning a turkey, an annual tradition since 1989, is the notion the turkey did something wrong to pardon. Supplied by the turkey industry’s advocacy body and bred for consumption rather than longevity, the pardoned turkey rarely lives long after its reprieve.

That’s just one of the incongruities linking turkey dinners to gratitude. Long domesticated in pre-Columbian North America, turkeys came to Europe with the Spanish in the early 1500s. Their English name reflects their resemblance to guineafowl, native to Africa and imported to Britain via Turkey in western Asia. Chancing on wild turkeys in fields or thickets was among the delightful surprises of my move to rural Wisconsin. They are huge. They scratch for food in our lawn and peck at our glass. Unlike their fattened, domesticated cousins, wild turkeys can fly to hide or roost in trees. Because they stay fairly low and don’t migrate, they offer hunters easy prey. Overhunting and deforestation cut their U.S. numbers to fewer than 30,000 in the 1930s, but they're now back up to more than seven million. As I wrote two years ago, the origins of American Thanksgivings in the 1800s had nothing to do with Pilgrims or Indians. Turkeys were plentiful and big enough to feed a family gathering. To share a meal in a spirit of love, abundance, and gratitude is a tradition worth keeping, regardless of the menu. Image: Ken Thomas, wild turkeys, 2008. I didn’t plan to write about Gaza. The conflict is too dire, with no clear path forward. But the final lectures in my Spanish Civil War series seemed to echo painful current newscasts. Unprovoked mass murder. Carpet bombing of cities, a novelty in 1937 when Picasso painted Guernica in protest. Attacks on refugees trying to flee.

My sympathies always lay with the Second Spanish Republic’s failed attempt to resist military rebels led by Francisco Franco. I’d read Hemingway and Orwell. Franco’s authoritarian dictatorship lasted well into my lifetime. Imagine my shock this month to learn the Spanish Republicans committed atrocities too. Their sympathizers slaughtered thousands of Catholic priests, monks, friars, and nuns early in the war. George Orwell described affluent citizens dressing as laborers for safety in the streets of Barcelona. Republicans killed fewer innocent civilians than did Franco’s Nationalists, but that doesn’t erase their crimes. An attorney speaking at my college long ago said choices are never between right and wrong. They are between alternatives that are each part right and part wrong. That doesn’t free us of responsibility to weigh imperfect options. The choice to stand back has consequences, too. Democracies in the 1930s declared neutrality toward Spain. Their isolationism left the fragile anti-fascist coalition dependent on the USSR for aid, while Germany and Italy sent bombers to help Franco win. Today my sympathies lie with Israelis and Palestinians killed, captured, or driven from their homes in and near Gaza. I hope someone wiser than me will find a way to make the suffering stop. There’s plenty of blame to go around. That's no reason to say, “A plague on both their houses.” Image: The ruins of Guernica, 1937 (cropped). German Federal Archives. Staying in the present has never been my strong suit. History and memory give my life context. Visions of the future give it purpose. Since my memories pull up more good times than grievances, and I usually look ahead with interest rather than dread, this seems pretty harmless unless it blinds me to the moment.

The problem comes when I’m half paralyzed by future unknowns I can’t control. Will my application be accepted? What will the medical tests show? Telling me “Don’t think about it now” is about as useful as saying not to think of a pink elephant. I do better to choose something absorbing to focus on instead, whether a game or a beautiful sunset. On a good day, stopping to smell the roses can crowd out anxiety for minutes at a time. On a bad day, roses aren’t enough. Then I try to reframe my nervousness as excitement. What makes mystery novels engrossing is precisely the fact that I don’t know what will happen next. Suspense is the point. If worrisome unknowns won’t leave me alone, I try to watch events unfold as if in a movie. Curiosity draws me forward. I won’t know the outcome until it happens, and maybe that’s okay. Image: On Grouse Mountain, Vancouver (cropped). What lies ahead? The drive from my West Virginia childhood home out to Cheat Lake and Coopers Rock passed an imposing building I remember as the Easton Convalescent Home (aka Eastmont Sanitarium). Such facilities in the first half of the 1900s offered tuberculosis patients rest, nutrition, fresh country air—and isolation from healthy loved ones. Like Covid in early 2020, TB or “consumption” was highly contagious and often fatal, with no vaccine or medicinal cure. Patients lived there until they healed or died.

Another classic time for convalescence followed childbirth. Some traditions called for a month of rest. My mother said she stayed in Providence Lying-In Hospital for a routine ten days after my birth. It was down to five days when my child was born. Now I see moms out and about with their newborns in a day or two. Convalescence has given way to quick cures and rehabilitation. Thank goodness for the medical advances that make this possible. But our cultural emphasis on productivity can press us to rush recovery faster than our bodies are ready. I’ve been in groups where it was almost embarrassing to check in with anything other than, “I’m so tired, I've been so busy.” When personal circumstances offer the luxury of a choice, I’d like to see “Take it slow, don’t push it” as frequent guidance for ourselves and others. Images by permission from West Virginia and Regional History Collection, West Virginia University Libraries. (left) Eastmont Sanitarium, Morgantown, W. Va. (right) Patients in Beds at Eastmont Sanitarium, Easton, Monongalia County W. Va. Fear helps us survive. It sharpens our awareness of potential threats and prepares us to fight or flee. If reckless teens seek out the adrenalin rush, more of us imagine threats at every turn. Overdone, the survival trait no longer serves us.

Halloween is a time to build tolerance for the scary we know to be safe. Horror movies do the same, though I avoid them. Susceptibility varies by nature, nurture, and age. The three-year-old frightened by Where the Wild Things Are will love the book at four. Nerve and resilience grow through controlled doses of exposure to a false threat, whether it’s new technologies (my bugaboo) or singing in public. “You gain strength, courage, and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face,” Eleanor Roosevelt said. What better place to start than with masked strangers at the door demanding treats? Photo by tracy ducasse. I cleared six-inch-high piles of papers off my desk. Some of the morass should have been tossed a year ago. One note was dated 2020. Admiring the nearly bare surface called to mind the phrase, “Draining the swamp.” For centuries people have drained marshes and swamps, sometimes to create solid ground for road construction or farming, sometimes to eliminate breeding places for disease-bearing insects.

In 1912 the socialist Victor Berger wrote, “We should have to drain the swamp—change the capitalist system—if we want to get rid of those mosquitos.” The next year, labor leader Mother Jones said of the bosses-vs-labor industrial system, “Let’s kill the virulent mosquito and then find and drain the swamp in which he breeds.” Politicians of both parties since the 1980s have used the metaphor variously to mean bureaucracy, lobbyists, corruption, terrorism, regulation, or government waste. Nothing noxious was breeding in the piles on my desk; that better describes a basement or refrigerator full of mold. My mess was, however, an impediment to fresh projects, the way literal swamps are impediments to agriculture or roads. And if the paper piles build up again, I could rework the metaphor to play on how swamps promote wildlife and safe weather. I’ve begun watching a lecture series on the Spanish Civil War. Though Spain in the 1930s had many distinctive aspects, some broader factors hold warning for the United States today.

Many Spaniards accepted the republican constitution of 1931 only so long as it served their objectives: secularization and land redistribution on one side, property rights and the Catholic Church on the other. Democracies work only if the majority respect their constitutions unconditionally. Playing by the rules matters more than any policy agenda. Responding to losses with “Not my president” or election denialism undermines democracy. In the early 1930s, political opinions in Spain ranged over a broad spectrum. Only a small minority admired Stalin on the left or Mussolini on the right. When the attempted military coup of 1336 triggered a brutal civil war, everyone had to choose sides. Violence breeds polarization and empowers the fringe. Never have I seen more condoning of political violence in the U.S. than in the past few years. As the two sides became increasingly identified with their extremes, what might once have been preferences or perspectives turned into moral imperatives. Combatants demonized their opponents. The non-negotiable defense of the Church or the working class excused any atrocity. Dehumanization rejects any outcome except total victory. After the rebels won in 1939, Francisco Franco ruled Spain as dictator until his death in 1975. I hope the United States still has time to learn from Spain’s example. Image: Bridge at Ronda, Spain. During the civil war, right-wing Nationalists allegedly threw left-wing Republicans to their deaths from the bridge. Parents, teachers, role models, and peers were the great personal influences of my youth. Among the many I never met were authors, journalists, celebrities, and occasional politicians. When did influences become influencers, and what changed along with the word?

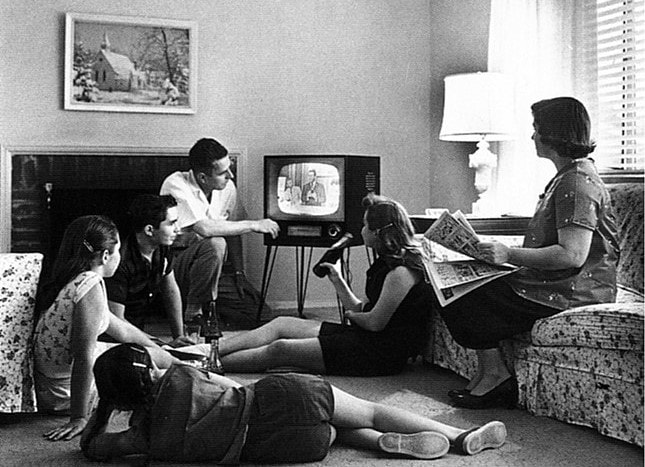

An influencer is someone with a large social media following who contracts to promote brands and products for profit. According to dictionary.com, this use of the word became widespread from about 2015. Far more than old-time television or billboards, social media make it possible to target large numbers in a precise niche. Influencers build a niche for the purpose of advertising other people’s products. Whoever grew up thinking, “I want to be a basketball star so I can make big money selling shoes?” Whereas traditional celebrity endorsements were an option for athletes and actors at or past the peak of their careers, young people today hope to become influencers to build their careers. A study a few years back found the notion of being a social media influencer appealed to 86 percent of participants age 13 to 38. The whole idea feels bizarre to me. I must be getting old. Image: The old media. Evert F. Baumgardner, family watching television, c. 1958, National Archives and Records Administration. As a child, long before I guessed family members would someday live somewhere in Africa, the continent intrigued me. Maybe it was from reading The Little Prince, set in the Sahara. Maybe it was from its size on our household globe, much of it labeled “French West Africa.” Picture books depicted Africa as a country like Mexico or Poland.

In recent adult conversations and study groups, I hear shock at role of Africans as sellers in the transatlantic slave trade. The white slavers who created the cruel market rarely captured human “cargo” by themselves. Africans were complicit. How could they have sold their own people into slavery? Who are “your own people”? No one expects people of India or China to identify primarily as Asian. No one seems aghast that France and Germany fought each other even though both are European. Africa in the heyday of the slave trade comprised dozens of nationalities such as the Yoruba, Bakongo, or Fulani. “Their own people” would be those of the same ethnicity. The idea of “Africa” scarcely existed. Pan-Africanism took shape only much later, outside Africa, among descendants of enslaved workers torn from their ethnic roots. Image: Africa from space. NASA.www.nasa.gov/image-feature/africa-and-europe-from-a-million-miles-away |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed