|

Shame can get you shunned. Humiliation can get you killed.

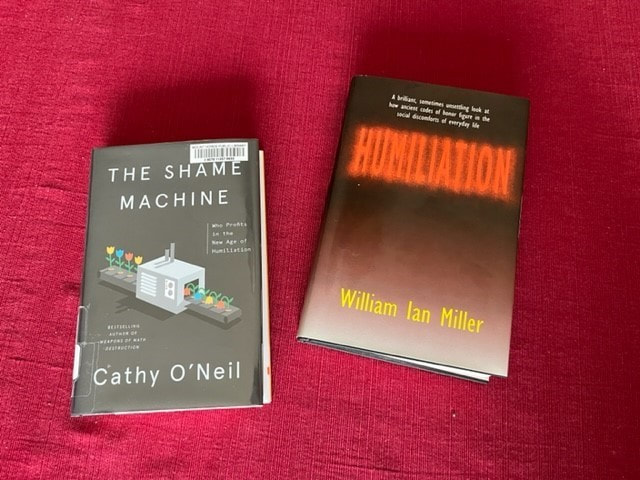

Shame is a tool to enforce norms of moral behavior. It’s also a weapon to accumulate wealth and power at the expense of people in need, data scientist Cathy O’Neil writes in The Shame Machine (2022). She explores how and why we shame those who are homeless, obese, addicted, mentally ill, undocumented, or formerly incarcerated. Requests for aid run up against complex paperwork, intrusive questions, and insurance denials. Food stamps and free school lunches put hardship on public display. Who gains? Blaming social problems on personal “bad decisions” lets everyone else off the hook. Privatization boosts corporate income. For-profit prisons and weight-loss programs thrive on repeat business. Humiliation is a different matter. It’s more about pride, reciprocity, and standing in the community than about morality. In the epics of medieval Iceland, law professor William Ian Miller (Humiliation, 1993) finds a culture in which reputation is all and insult is repaid with violence. Similar traits mark the honor societies of the Old South and the urban gangland. They tinge playground bullying and adult anxiety about throwing a party to which nobody comes. Hypocrisy lies at the intersection of shame and humiliation. The politician who campaigns on family values, later revealed as a sexual predator, invites both reproach and ridicule. Humiliation is always cruel, whether or not it’s deserved. Shame, on the other hand, aimed upward at public figures who abuse their power, has potential to bring reform and reconciliation.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a historian who writes novels and literary nonfiction. My home base is Madison, Wisconsin. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed